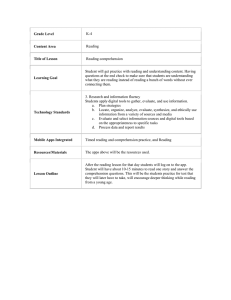

DIRECT INSTRUCTION AND PROMOTING INTERACTION IN LEARNING VERSUS LEARNING INDEPENDENTLY

advertisement