\begindata{text,538858664} \textdsversion{12} \template{default} \define{footnote

advertisement

\begindata{text,538858664}

\textdsversion{12}

\template{default}

\define{footnote

attr:[Flags OverBar Int Set]

attr:[FontSize PreviousFontSize Point -2]}

\define{keyword

}

\define{function

}

\define{para

menu:[Justify~2,Para]

attr:[Indent LeftMargin Cm 43927]}

\define{code

menu:[Justify~2,Code]

attr:[LeftMargin LeftMargin Cm 83230]

attr:[Indent LeftMargin Cm 0]

attr:[FontFamily AndySans Int 0]}

\define{bullist

menu:[Justify~2,Bullist]

attr:[LeftMargin LeftMargin Cm 99414]

attr:[RightMargin RightMargin Cm 83230]

attr:[Indent LeftMargin Cm -16183]

attr:[Tabs TabClear Point 18]

attr:[Tabs TabClear Point 14]

attr:[Tabs LeftAligned Point 7]}

\define{class

}

\define{comment

}

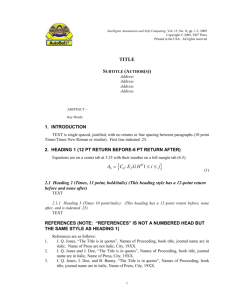

\chapter{The Print Class

}

\code{\keyword{static} \keyword{int}

\function{\bold{print::ProcessView}}(\keyword{

}\leftindent{\keyword{class} view *v,\keyword{

int} print,\keyword{

int} dofork,\keyword{

char} *DocumentName,\keyword{

char} *prarg)

}}

\para{This prints or previews the view \italic{v}. \

The \italic{print} argument specifies a printing mechanism, and also

specifies whether the document is to be printed or previewed. The values

\typewriter{print_PRINTTROFF}, \typewriter{print_PREVIEWTROFF},

\typewriter{print_PRINTPOSTSCRIPT}, and

\typewriter{print_PREVIEWPOSTSCRIPT}

can be used.

If \italic{dofork} is TRUE, the print or preview command will work

asynchronously (in the background.) If \italic{dofork} is FALSE, the

command will execute synchronously, and ProcessView will not return until

the command is complete. Note that printing commands are considered

complete when the print job is successfully queued; but previewing

commands

are often not considered complete until the user has finished looking at

the document and closed the viewing window.

\italic{DocumentName} is a hint. The printing mechanism may use this to

display a filename on a banner page or window title bar. If you set this

to

NULL, \italic{ProcessView} will make something up.

\italic{prarg} is an optional list of extra arguments to be passed

directly

to the printing command. Use NULL to specify no extra arguments. If the

\italic{print} parameter specifies previewing, \italic{prarg} is ignored.

\

}

\code{\keyword{static} \keyword{char} *

\function{\bold{print::GetPrintCmd}}(

\leftindent{\keyword{int} print)

}}

\para{This returns the command which will be used by the operation

specified by \italic{print}. This parameter has the same meaning as in

\italic{ProcessView} (described above.)

You will normally not have to call this function. \

}

\subsection{A Walkthrough of the

PostScript\footnote{\

\begindata{fnote,540716184}

\textdsversion{12}

PostScript is a trademark of Adobe Systems Incorporated.\

\enddata{fnote,540716184}

\view{fnotev,540716184,205,0,0}} Printing System, with Function Calls

}

\para{A printing job is initiated the same way it was in the old

mechanism

-- by a function which is bound to the "Print" menu option. This function

calls \italic{print::ProcessView} with the print parameter set to

\typewriter{print_PRINTPOSTSCRIPT} or

\typewriter{print_PREVIEWPOSTSCRIPT}.}

\para{In this case, \italic{print::ProcessView} sets up the environment

for

a PostScript printing job. This includes: \

}\bullist{\symbol{\^{7}}

write

to;

\symbol{\^{7}}

definitions;

opening a temporary file for \italic{v} to

preparing empty hash tables for v to register fonts and

\symbol{\^{7}}

looking through the print options (page size, print

scale,

landscape mode). \

}It then calls \italic{v}'s main PS printing method,

\italic{view::PrintPSDoc}.

\code{virtual void \bold{view::PrintPSDoc}(

\leftindent{FILE *outfile, \

long pagew, long pageh)

}}

\para{\italic{outfile} is the file that the view will be writing its

output

to. This does \italic{not} include PS comment headers and body headers;

these will be prepended later by the printing mechanism. \

\italic{pagew} and \italic{pageh} give the size of the page that the view

should format its output for (in PS units, 1/72 inch.) This is normally

612

by 792, specifying 8.5"x11"

paper\footnote{\

\begindata{fnote,540719800}

\textdsversion{12}

One of these days it will understand different paper sizes. That day is

not

yet.\

\enddata{fnote,540719800}

\view{fnotev,540719800,206,0,0}}; but this may be altered by the user's

landscape and scaling print options. For example, if landscape mode is

set,

the print mechanism would pass dimensions of 792 by 612 instead. \

The view is now in control of the printing process, and can generate any

PostScript code it wants. However, it must conform to certain

constraints. \

}

\subsection{Methods To Be Called During Printing

}

\para{Each page of output must be preceded by a call to

\italic{print::PSNewPage}.

}

\code{\keyword{static} boolean

\function{\bold{print::PSNewPage}}(\keyword{

}\leftindent{\keyword{int}

pagenum)

}}

\para{The view should set \italic{pagenum} to the number of that page.

(This need not be a simple 1, 2, 3... series; if the document represents

a

single chapter of a book, the page numbering might begin at a higher

number. If the view doesn't maintain a separate notion of page numbering,

and is willing to accept 1, 2, 3..., it can pass in the constant

\typewriter{print_UsualPageNumbering}.) \

\italic{print::PSNewPage} transparently handles several things. \

}

\bullist{\symbol{\^{7}}

begin a new

page of output.

It generates the appropriate PS code to

\symbol{\^{7}}

It generates PS code to handle landscape and scaling

options, so that the view's printing commands come out in the correct

place

on the page.

\symbol{\^{7}}

It compares \italic{pagenum} to the "range of pages to

print" print option. If the page should be printed,

\italic{print::PSNewPage} returns \typewriter{TRUE}. If not, it returns

\typewriter{FALSE}; this tells the view that it must skip generating any

PS

for this page. (not yet implemented)

\symbol{\^{7}}

If an "N-up" print option is set, it can generate PS

commands to scale the page down and move it to the appropriate place on

the

page, or begin a new page of output if this is the Nth page. (not yet

implemented)

\symbol{\^{7}}

Finally, if \italic{view::PrintPSDoc} exits without ever

calling \italic{PSNewPage}, the printing mechanism knows that the view

cannot be printed, and gives an error message. Note that this means that

an

empty view must call \italic{PSNewPage} once, not zero times, to print a

blank page.

}

__________________________________

\para{The view should also register PostScript definitions that it plans

to

use, with the \italic{print::PSRegisterDef} call. By registering them

with

the printing mechanism, it ensures that commands aren't multiply defined

(even if that type of view is printed several times in a document.) It

also

ensures that all commands are defined in the correct place in the final

PostScript (in the prologue, before the first page begins.) It also means

that we do \italic{not} need a static list of headers included in each

document. \

}

\code{\keyword{static} \keyword{void}

\function{\bold{print::PSRegisterDef}}(

\leftindent{\keyword{char}

char}

}}

*procname, \keyword{\

*defstring)

__________________________________

\para{If the view wants more complex PostScript code in the prologue, it

can register a callback procedure to generate arbitrary output. \

}

\code{\keyword{\keyword{typedef} \keyword{void}

(*\bold{print_header_fptr})(\keyword{FILE *outfile, void} *rock);

static} \keyword{void} \function{\bold{print::PSRegisterHeader}}(

\leftindent{char *headname,

print_header_fptr headproc, \keyword{\

void} *rock)}}

\para{The \italic{headname} string is just used to uniquely identify

callbacks. A callback is called only once in the header even if it is

registered several times by different instances of the view. You must

ensure that if \italic{PSRegisterHeader} is called more than once with a

particular headname, the headproc and rock are the same on each call. If

they are not, the results are undefined.

The header that you create should not alter the graphics environment in

any

way. You may not alter the current path, color, transformation, etc. If

you

want to do any of these things, the header should be surrounded by

\typewriter{gsave} and \typewriter{grestore}. (The printing module takes

some precautions to protect the environment against violations of this

rule; but they are not perfect and you should not rely on them.)

Note that definitions registered by \italic{PSRegisterDef} will appear

before text registered by \italic{PSRegisterHeader}. However, you can

make

no other assumptions about the order of items in the PostScript prologue.

}

__________________________________

\para{A similar mechanism, \italic{print::PSRegisterFont}, allows the

view

to register PS fonts that it plans to use. This allows the printing

mechanism to generate a correct \typewriter{%%DocumentFonts} header

comment. \

}

\code{\keyword{static} \keyword{int}

\function{\bold{print::PSRegisterFont}}(

\leftindent{\keyword{char}

*fontname)

}}

\para{The integer returned by \italic{PSRegisterFont} is a key which can

be

conveniently stored to refer to the font. The view can use the command

}\code{fprintf (outfile, "%s%d %d scalefont setfont\\n",

print_PSFontNameID, keyvalue, fontsize);

}to generate a PS command to set the current font to the font whose key

is

\italic{keyvalue} and whose size is \italic{fontsize} points.

__________________________________

\para{Finally, there is a mechanism to register callbacks to clean up

after

the printing job is completed. The printing of text objects is so icky

that, in places, objects are created which must persist through the

entire

printing job.

}

\code{\keyword{\keyword{typedef} \keyword{void}

(*\bold{print_cleanup_fptr})(\keyword{void} *rock);

static} \keyword{void} \function{\bold{print::PSRegisterCleanup}}(

\leftindent{print_cleanup_fptr cleanproc, \keyword{\

void} *rock)

}}

\para{This registers the function pointer and rock; when the job is

completed, each registered pointer will be called and given its rock as

its

argument. Note that each callback is called once for each time it is

registered. (This is different from \italic{PSRegisterHeader}, which

allows

each callback to be called exactly once, even if it is registered several

times.)

}

__________________________________

\para{That sums up what \italic{PrintPSDoc} has to do; use the five

printing callbacks described above, and dump PS code to \italic{outfile}.

Note that the printing callbacks can \italic{only} be called during a

printing job -- that is, within a call to some view's \italic{PrintPSDoc}

method. If they are called under other circumstances, they will return

immediately and have no effect.

}

\subsection{Printing Helper Methods

}

\para{In contrast, the following helper functions are always available.

They may be called when there is no printing job in progress, and they do

not affect the state of the printing job if there is one.

}

__________________________________

\code{\keyword{static} boolean

\function{\bold{print::LookUpColor}}(\keyword{

}\leftindent{\keyword{char} *name, \keyword{\

double} *rval, \keyword{double} *gval, \keyword{double} *bval)

}}

\para{Given the name of a color, return the red, blue, and green values

which comprise it.

}

__________________________________

\code{\keyword{static} \keyword{short}

*\function{\bold{print::EncodeISO8859}}()

}

\para{This returns an encoding vector which maps the ISO8859-1 (Latin-1)

character set to the generic AGP encoding used by the PS printing

mechanism. The vector can be considered a 256-element array of short

ints.

If you have a text character which you know is from a ISO8859-1 text, you

can convert it to an AGP value, using code like the following:

}

\code{char ch; /* this is the original character value */

short *encoding;

short agpval; /* the final result */

encoding = print::EncodeISO8859();

agpval = encoding[(unsigned char)ch];

}

\para{Note particularly the expression \code{encoding[(unsigned

char)ch]}.

The cast to unsigned char is very important -- if \italic{ch} has its

high

bit set, you want to look in the range \italic{encoding[128..255]}, not

\italic{encoding[-128..-1]}.

If the result \italic{agpval} is negative, the character has no printed

representation, and should be treated as a zero-width blank. \

}

\code{\keyword{static} \keyword{short}

*\function{\bold{print::EncodeISO8859}}()

}

\para{This returns an encoding vector which maps the Adobe Symbol

character

set to AGP encoding. \

Note: normally, you will not call either of these functions yourself. The

\italic{LookUpPSFont} function (described below) will look up the

encoding

vector appropriate to any screen font, which you can then use with all

characters displayed in that font.

}

__________________________________

\code{\keyword{static} boolean

\function{\bold{print::LookUpPSFont}}(\keyword{

}\leftindent{\keyword{char}

short}

**encoding, \keyword{\

class} fontdesc

char}

*result, \keyword{\

*fd, \keyword{\

*family, \keyword{long} size, \keyword{long} style)

}}

\para{This function accepts either a AUIS font description \italic{fd},

or

(if \italic{fd} is NULL) a font family name, size, and style. It returns

the name of the PS font which matches that description, and the font's

encoding vector (see above.) All standard AUIS screen fonts use either

the

ISO8859-1 or the Adobe Symbol encodings; so the encoding vector will

mostly

likely be one of the two described in the previous section.

}

__________________________________

\code{\keyword{static} \keyword{struct} font_afm

*\function{\bold{print::GetPSFontAFM}}(\keyword{

}\leftindent{\keyword{char}

*fontname)

}}

\para{Given a PS font name, this loads the AFM (Adobe Font Metric) file

associated with that font and returns a pointer to the result. See below.

}

__________________________________

\code{\keyword{static} \keyword{void}

\function{\bold{print::OutputPSString}}(

\leftindent{FILE *outfile, \keyword{\

char} *str, \keyword{\

int} maxlen)

}}

\para{Takes the string \italic{str} and writes it to \italic{outfile},

using PS string escaping to quote any character which needs to be quoted

in

a PS string literal. It does not write the delimiting parentheses of a PS

string literal. A maximum of \italic{maxlen} characters are written; to

write up to a \\0 delimiter, set \italic{maxlen} to -1.

This function assumes that \italic{str} is already in the PS character

encoding. The caller must ensure the string is encoded before

\italic{OutputPSString} is called. If the string contains only 7-bit

printable ASCII characters, no encoding is necessary. For a more

convenient

way to generate PS from AUIS strings, see \italic{GeneratePSWord}.

}

__________________________________

\code{static double \bold{print::ComputePSCharWidth}(

\leftindent{int

chi, \

struct font_afm *afm, \

int

fontsize)

}}

\para{This returns the width (in PS units) of the character \italic{chi}.

\italic{chi} should be in the AGP encoding; \italic{afm} is the fontmetric

structure for the font you want to measure in, and \italic{fontsize} is

the

point size of the font.

Confused? It works like this. \

}

\code{\keyword{class} fontdesc *yourfontdesc; /* you should have this set

to the font you want to measure */

int size; /* you should have this set to the point-size of the font you

want to measure */

char ch; /* the character you want to measure */

short *encoding;

char psfontname[64];

struct font_afm *afm;

double width; \

print::LookUpPSFont(psfontname, &encoding, yourfontdesc, NULL, 0, 0); /*

looks up the font name and encoding for the fontdesc you provide */

afm = print::GetPSFontAFM(psfontname); /* look up the AFM data */

width = print::ComputePSCharWidth(encoding[(unsigned char)ch], afm,

size);

}

\para{Note particularly the expression \code{encoding[(unsigned

char)ch]}.

The cast to unsigned char is very important -- if \italic{ch} has its

high

bit set, you want to look in the range \italic{encoding[128..255]}, not

\italic{encoding[-128..-1]}.

If you are not working from a particular screen font, you will have to

provide the encoding vector and PS font name yourself. Most text in AUIS

is

ISO8859-1 text. (This includes any text which is 7-bit ASCII. The first

128

characters of the ISO8859-1 encoding are identical to the 7-bit ASCII

characters.) \

To get the ISO8859-1 encoding, use this code:

}\code{short *encoding = print::EncodeISO8859();

}\para{If you want to measure a string using the "symbol" screen font,

use

this instead:

}\code{short *encoding = print::EncodeAdobeSymbol();

}(conveniently, the "symbol" screen font uses the same encoding as the

Adobe Symbol PS font.)

__________________________________

\code{static void \bold{print::GeneratePSWord}(

\leftindent{FILE

char

int

*buf, \

len, \

double

short

xpos, \

*encoding, \

struct font_afm

int

*outfile, \

*afm, \

fontsize)}\leftindent{

}}

\para{This is it -- the routine to generate the PS code to print a text

string. \italic{outfile} is the file to print to; \italic{buf} is the

string; \italic{len} is the number of characters to print; \italic{xpos}

is

the horizontal position (in PS units) to start printing at. \italic{\

encoding} is the encoding vector you got from \italic{LookUpPSFont};

\italic{afm} is the AFM data you got from \italic{GetPSFontAFM};

\italic{fontsize} is the point size of the font. For a full explanation

of

these parameters, see the discussion above about using

\italic{ComputePSCharWidth}.

Note that \italic{buf} should be a buffer to the original string data;

you

do not have to convert the character values by looking them up in

\italic{encoding[]}. The \italic{GeneratePSWord} function does that for

you.

Although this function is called \italic{GeneratePSWord}, it will

correctly

display strings which contain spaces. It will \italic{not} do anything

with

tabs or linefeeds; they will be treated as zero-width blanks, just like

all

other non-printable characters. If you want tabs or linefeeds to behave

sensibly, you will have to break the string up yourself and call

\italic{GeneratePSWord} several times. You will also have to do this if

you

want to put additional whitespace between words (for full justification.)

The vertical (baseline) position of the string is assumed to be stored in

a

PostScript identifier called \code{tY}. Before calling

\italic{GeneratePSWord}, you should output PostScript code such as

}\code{/tY 130.5 store

}\para{(substituting the desired vertical position for

\typewriter{130.5},

of course.) This is efficient in the usual case of printing several words

on the same line. However, remember that \code{tY} is effectively a

global

variable, and other views may store values in it. If your code calls

another view's printing method, the value of \code{tY} will be undefined

after that method returns, and you should store your vertical position

again before your next call to \italic{GeneratePSWord}.

You need not register the definition of \code{tY};

\italic{GeneratePSWord}

will call \code{PSRegisterDef("tY", "0")} to register the definition with

a

dummy value of 0.

}

\subsection{A Word About Dictionaries

}

\para{In PostScript, definitions for identifiers are stored in

dictionaries. Each dictionary has a fixed size; only a given number of

definitions can be stored in each dictionary.

All the definitions that you create using \italic{PSRegisterDef},

\italic{PSRegisterHeader}, and \italic{PSRegisterFont} are stored in a

dictionary called atkDict. That dictionary is opened at the beginning of

the PS file and remains open until the end. It is exactly big enough to

hold all the registered definitions, and no more. This means that if you

place any unregistered "def" statements in the PS output, you will cause

a

"dictionary full"

error.\footnote{\

\begindata{fnote,540749896}

\textdsversion{12}

Warning: ghostscript, the most common PostScript previewer, allows

dictionaries to be overfilled without giving an error. This means that

you

can accidentally create PS files which look correct in ghostscript, but

cause errors when printed or viewed with other software. Be careful.\

\enddata{fnote,540749896}

\view{fnotev,540749896,207,0,0}}

If you want a temporary space in which to store values during your

printing

process, you should register it with \italic{PSRegisterDef,} giving it a

dummy value. Then store values into it using "store" instead of "def".

It is also possible to create your own dictionaries. Use a statement like

}\code{print::PSRegisterDef("yourdictname", "20 dict");

}where \italic{yourdictname} is the name you have chosen and \italic{20}

is

the number of definitions you need. Then you can say

\code{print::PSRegisterHeader("yourheaderid", headerproc, NULL);

}where \italic{yourheaderid} is a unique string and \italic{headerproc}

is

a function which generates PS output like the following:

\code{yourdictname begin

\italic{PS code to define entries

}end

}

\para{This will cause the dictionary to be defined and filled in the PS

prologue. (Remember that if your view appears as an inset, it may appear

more than once, and thus make these registration calls more than once.

Nonetheless, the dictionary will be created and defined exactly once.)

During printing, you may then open and close the dictionary as usual

(using

"begin" and "end") and use the definitions in it. Remember to close any

dictionary you open; this helps prevent possible conflicts between

insets.

Also, if your view is about to call an inset's PrintPSRect method (see

below), you should close any dictionaries you have opened, to avoid

conflicts. \

It is possible to create definitions in the built-in dictionary userdict,

by using the "put" statement. This is not recommended, since there is no

easy way to tell how big userdict is or whether it is full.

}

\subsection{Printing Insets

}

\para{There are at least two different ways that substrate views can

print

their insets. The naive way is that the parent selects a rectangle on the

page, and the child generates PS code that draws an image in that

rectangle. However, there are also insets that are designed solely to be

placed in text; they are not printed on the page, but instead affect how

the text is formatted. Examples of this latter type are page break

insets,

footnotes, and the header/footer inset.

To allow both of these methods, and leave room for others, the new

printing

mechanism introduces the idea of \italic{printtypes}. A printtype is just

a

protocol for the parent and child to negotiate how the printed page will

look. \

If a view has child views, the parent calls each child's

\italic{view::GetPSPrintInterface} method to determine how that child

should be printed.

}

\code{\keyword{virtual} \keyword{void}

*\function{\bold{view::GetPSPrintInterface}}(\keyword{

}\leftindent{\keyword{char} *printtype)

}}

\para{\italic{printtype} is a string which specifies the exact mechanism

the parent is asking about. The child returns non-\typewriter{NULL} if it

can be printed with the given printtype, and \typewriter{NULL} if it

cannot. Depending on the printtype, the returned non-\typewriter{NULL}

value may contain additional information. \

Note that if the child returns NULL, the parent may call

\italic{GetPSPrintInterface} again with a different printtype. A

substrate

may be able to print its children with several different printtypes; it

is

up to the parent to choose one. Similarly, a child view may be able to be

printed with several different printtypes.

AUIS currently supports two printtypes. The naive

draw-yourself-in-a-rectangle printtype is called "\typewriter{generic}";

the protocol by which special insets negotiate with textview is called

"\typewriter{text}".

}

\italic{The \typewriter{generic} protocol}

\para{This is the most common protocol; all the substrates (text, figure,

and table) allow their children to be printed with it, and all the major

data types can be printed as children under it. In fact, it is common

enough that there are methods in class view to support it. \

}

\code{\keyword{virtual} \keyword{void}

\function{\bold{view::DesiredPrintSize}}(\keyword{

}\leftindent{\keyword{long} width, \keyword{long} height, \keyword{\

enum} view_DSpass pass, \keyword{\

long} *desiredwidth, \keyword{long} *desiredheight)

}\keyword{virtual} \keyword{void} \function{\bold{view::PrintPSRect}}(

\leftindent{FILE *outfile, \keyword{\

long} logwidth, \keyword{long} logheight, \keyword{\

struct} rectangle *visrect)

}}

\para{This works as you might expect. \

First the parent verifies that

\italic{child->GetPSPrintInterface("generic")} returns non\typewriter{NULL}

(the returned value is not otherwise meaningful). \

Then the parent calls the child's \italic{DesiredPrintSize} method,

passing

in the dimensions of the rectangle that it intends to give (in PS units,

1/72 inch.) It also passes in a \italic{pass} value which indicates which

dimensions it is willing to be flexible on. The child returns its

preferred

dimensions, which the parent is free to modify or ignore. \

Then the parent calls the child's \italic{PrintPSRect} method.

\italic{logwidth} and \italic{logheight} are the rectangle dimensions the

parent has decided upon. (The rectangle starts at the origin -- the

parent

is responsible for generating PS code which translates this to the

correct

part of the parent's page.) If the parent knows that part of this

rectangle

will be not visible (off the page, for example, or overwritten by other

parts of the image), it may pass this information in by setting

\italic{visrect}. \italic{visrect} is the part of the drawing rectangle

which is actually drawable; the child can optimize by not drawing data

that

lies outside

\italic{visrect}.\footnote{\

\begindata{fnote,540759608}

\textdsversion{12}

\define{italic

menu:[Font~1,Italic~11]

attr:[FontFace Italic Int Set]}

Note that the parent is responsible for setting the PS clipping region

before calling \italic{PrintPSRect}. The child is allowed to ignore

\italic{visrect} and draw outside it, and even to draw outside the main

rectangle.\

\enddata{fnote,540759608}

\view{fnotev,540759608,208,0,0}} \

The parent is reponsible for saving the PS drawing state before a call to

\italic{PrintPSRect}, and restoring it afterwards.

}

\italic{The \typewriter{text} protocol}

\para{A full explanation of this would require a full explanation of the

textview printing algorithm, which is painful. However, in brief, the

call

to \italic{GetPSPrintInterface("text")} returns a pointer to a

\class{\italic{textview_insetdata} }structure, which the child has filled

out to indicate what special behavior it wants from the parent text. The

possibilities include:

}

\bullist{\symbol{\^{7}}

The child provides a textview which the

parent text

should print out at this point (just as if the text had been pasted into

the parent.)

\symbol{\^{7}}

The child provides a character string which the parent

text

should print out at this point. The child may also provide a single style

to be wrapped around the string.

\symbol{\^{7}}

The parent should begin a new page.

\symbol{\^{7}}

print

The child provides a textview which the parent should

as a footnote at this point.

\symbol{\^{7}}

The child provides a header or footer which the parent

should use from this point on.

\symbol{\^{7}}

The child provides a text tag at this point.

\symbol{\^{7}}

The child provides a reference to a given text tag.

}

\para{The first two of these (pasted textview and pasted string) are the

only ones likely to be used by new insets. \

}

\section{Creating Complete PostScript files }\

\para{A complete PostScript file has headers, a sequence of pages

generated by \italic{view::PrintPSDoc} or \italic{view::PrintPSRect}, and

finally some trailers. A print object can be utilized to create a

complete

PostScript file with appropriate headers and trailers. When a

\italic{print} object is created, it does some initialization and opens a

temporary file to receive the contents of the PostScript file that will

be

generated by \italic{view::PrintPS...}. The client uses the

\italic{GetFILE} method to get a pointer to this FILE* object and passes

this as the FILE* argument to the\italic{ view::PrintPS...} methods. The

complete file is then written with a call to \italic{WritePostScript}.

All of the functions defined in earlier sections that can be called while

a

print is in progress can be called while a print object is in existence.

In particular, the definitions registered with the

\italic{PSRegister...}

calls are correctly inserted in the generated file.

In addition methods are available to set the print parameters that would

otherwise be set by the \bold{Printer Setup} menu option. These are the

parameters:

}

\leftindent{\description{Landscape - a boolean.

image a quarter turn counter-clockwise.

When True, rotates the

Scale - a double. Values less than one produce a smaller image and

bigger

values enlarge the image.

PaperSize - two int values.

printed on.

Filename - char *.

print object.

Title - char *.

The width and height of the page to be

The name of the file which will be created by this

The title which will be written in the file's header.}}

The parameters are fetched and set with the following methods:

\code{void \bold{SetLandscape}(boolean v) \

boolean \bold{GetLandscape}() \

void \bold{SetScale}(double v) \

double \bold{GetScale}() \

void \bold{SetPaperSize}(int width, int height) \

void \bold{GetPaperSize}(int *width, int *height) \

void \bold{SetFileName}(char *fnm) \

char *\bold{GetFileName}() \

void \bold{SetTitle}(char *tnm) \

char *\bold{GetTitle}() }\

\para{The method }\

\code{void \bold{SetFromProperties}(

\leftindent{view *v, \

long *pwidth, long *pheight);}}

interrogates the view for any print option properties that may have been

set by \bold{Printer Setup}. The values of *pwidth and *pheight, if

non-NULL, will be set to the width and height for the object to be

printed.

This can differ from the page size because it honors scaling and the

landscape parameter. It is generally best to call this method after

setting the parameters with the explicit methods above.

\para{Actual creation of PostScript code is performed by two methods:}

\code{FILE* \bold{GetFILE}()

boolean \bold{WritePostScript}(

char *filename, \

char *title);}

\italic{GetFILE} returns a \italic{FILE*} value which is for an internal

file utilized by the print object. It is this file into which the

PostScript for pages must be generated. After the PostScript pages have

been written, a call to \italic{WritePostScript} creates a file named

\italic{filename} and having the \italic{title} given. Either of the

arguments can be NULL, in which case the values set by \italic{SetTitle}

or

\italic{SetFilename} will be used. If the file name is not specified in

either way, the print object will try to make up a reasonable name by

searching for a buffer containing the view and using its file name. If

all

else fails, the file will be named by the tmpnam() function; this is

rarely

useful.

\para{The code just below is one way to utilize a print object for

generating a PostScript file. The declaration \italic{print p} is an

automatic declaration and creates a print object when the scope is

entered;

the object is destroyed when the scope exits. The \italic{p.Set...}

calls

set attributes of the print; the call to \italic{SetFromProperties} will

honor any print parameters set for the view (as with the \bold{Printer

Setup} menu item). }\

\code{long pagew, pageh;

print p;

// printing context

p.SetPaperSize(width, height);

p.SetScale(scale/100.0);

p.SetFromProperties(v, &pagew, &pageh);

v->PrintPSDoc(p.GetFILE(), pagew, pageh);

if ( ! p.WritePostScript(tfnm, NULL)) \

;

// should print an error message here

// ... process tfnm

unlink(tfnm);}

Note that there are TWO files involved. The file named \italic{tfnm} is

the desired full PostScript file and is created and written by the call

to

\italic{WritePostScript}. In this application, \italic{tfnm} is a

temporary file, so the client unlinks it when done. The other file is

created by the constructor for the print object and utilized as the FILE

argument to \italic{PrintPSDoc} by the call to \italic{p.GetFILE}. This

file is copied into \italic{tfnm} as part of the \italic{WritePostScript}

operation and is deleted by the destructor for the print object.

\para{Each \italic{print} object can be used only once to create a

PostScript file. To create another file, another \italic{print} object

must be created.

A \italic{print} object may be created even while another already exists.

The most recently created (and not yet deleted) \italic{print} object is

returned by}

\code{static print *\bold{print::GetCurrentPrint()}}

Note that \italic{PSRegister...} calls apply only to the print operation

that is the value of \italic{GetCurrentPrint}. When a print is initiated

by \italic{print::ProcessView}, it creates a \italic{print} object which

becomes the value of \italic{GetCurrentPrint}; this value can be used to

access the data members of that print operation.

\subsection{A Final Word About Coordinates}

\para{There are several places in the printing mechanism (notably the

methods for the "generic" printtype) where rectangles are given in PS

coordinates. This involves a problem. The AUIS struct rectangle has

members

\italic{left}, \italic{top}, \italic{width}, and \italic{height}; this is

because it is usually used with AUIS screen coordinates, whose origin is

in

the top left. But PS coordinates put the origin in the bottom left. What

to

do?

What to do is this: accept the names of the members as correct.

\italic{left} is the X coordinate of the left edge; \italic{width} is the

(positive) width of the rectangle. \italic{top} is the Y coordinate of

the

top edge of the rectangle; \italic{height} is the (positive) height of

the

rectangle. This means that \italic{top} has a \italic{greater} numerical

value than the Y coordinate of the bottom edge. The bottom edge can be

computed as \italic{(top-height)}. This is different from rectangles in

view coordinates, whose bottoms can be computed as \italic{(top+height)}.

This means that many of the macros and functions in

\typewriter{rectangle.h}

cannot be used with PS rectangles. Notably, \italic{rectangle_Bottom}

will

do the wrong thing. However, \italic{rectangle_IsEmptyRect} will work,

because it is still true that a rectangle with negative width or height

is

empty.

Why did I choose to do it this way? Because it confuses me least. It

might

have made more sense to define an entirely new type, and allow C++

type-checking and overloading to take care of the situation. \

}

\enddata{text,538858664}