Document 16110370

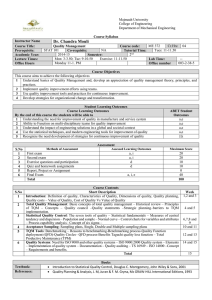

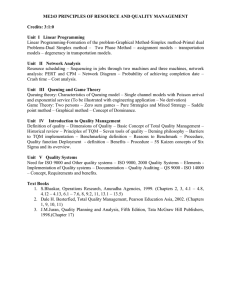

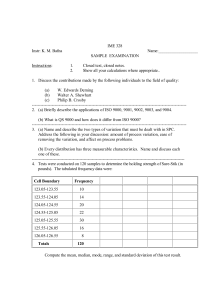

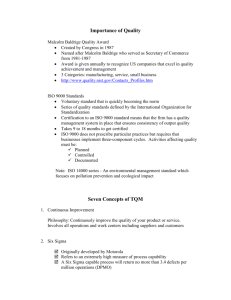

advertisement