BIG BROTHERS BIG SISTERS OF GREATER SACRAMENTO GUARDIAN AND

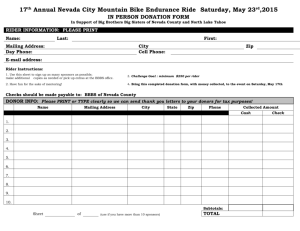

advertisement