Chapter 8 - Money CHAPTER 8. MONEY ...................................................................................................... 1

advertisement

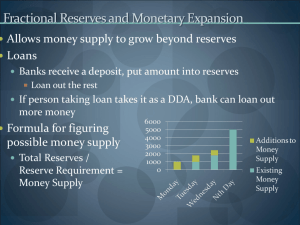

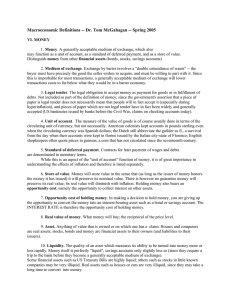

Chapter 8 - Money CHAPTER 8. MONEY ...................................................................................................... 1 I. The U.S. Experience with Money ........................................................................... 2 I. The U.S. Experience with Money ............................................................................... 2 a medium of exchange ....................................................................................... 2 seigniorage, ........................................................................................................ 3 standard of value ............................................................................................... 3 store value .......................................................................................................... 4 2. The Definition of Money ..................................................................................... 4 M1 ....................................................................................................................... 5 M2 ....................................................................................................................... 5 M3 ....................................................................................................................... 5 Table 8-1. Different Definitions of Money ............................................................. 5 3. The Federal Reserve System .............................................................................. 6 Federal Reserve System ...................................................................................... 6 Clearinghouse for checks ............................................................................................ 6 Reserve accounts ......................................................................................................... 6 Loans of Reserves ....................................................................................................... 6 Cash............................................................................................................................. 6 Figure 8-1. How the Fed Works.......................................................................... 6 1. Setting the reserve requirement. ......................................................................... 7 2. Determining the Discount Rate ............................................................................. 7 3. Open Market Operations ....................................................................................... 7 4. Setting Up a Bank ............................................................................................ 7 Figure 8-3 ............................................................................................................... 9 Figure 8-4 ............................................................................................................. 10 5. Changing the Reserve Requirement ........................................................... 10 Figure 8-5. ............................................................................................................ 11 6. Open Market Operations .................................................................................. 12 Figure 8-6. ............................................................................................................ 12 7. Discounting ............................................................................................................. 13 Figure 8-7. ............................................................................................................ 14 8. Money Multiplier Through the Entire Banking System ........................ 15 Table 8-2. .............................................................................................................. 16 Figure 8-8. ............................................................................................................ 17 9. Conclusion .............................................................................................................. 17 \CHAPTER 8. MONEY Very rarely do we have to stop to think about where the value for money comes from. Yet we spend so much of our lives working extremely hard to gain enough of this value so that our lives, families, and communities can be secure and enjoyable. However, maintaining the value of money is an ongoing experiment that governments are 1 Chapter 8 - Money continually trying to learn how to manage. Through history governments have come up with new ways to manage money that provide important insights into the value of money. I. The U.S. Experience with Money An understanding of the value and government management of money can be illustrated by examining the history of the American experiment with money. Before the European colonists came to America, there was a strong system of barter that carried goods across the country. In barter arrangements there is no money. One item is exchanged for another. However, when someone really needs something, it is expensive to search for something that will be acceptable in a barter exchange. It’s much easier to have something that everyone values and to keep it around so that it is always available for exchange. Money can provide such a value if everyone agrees to its value. If everyone seems to be willing to exchange items of value for money, then people are continually reassured that it has value. Trust that others will accept money as a medium of exchange is crucial. But who decides what is valuable? Historically, certain scarce items have caught people’s attention and through experience people find that others will accept these items as exchange. The items have simply evolved into the role of money without any formal recognition. Certain items like shells have migrated across the American continent and have similarly been found to play the role of money in other cultures (http://www.richmondfed.org/about_us/our_tours/money_museum/virtual_tour/monies/pr imitive_money/index.cfm) Like other forms of early money shells facilitated exchange because they had (1) high value per unit which meant little of it was needed, (2) low weight which meant it was not too heavy to carry, (3) high durability which meant that it preserved its value, and (4) wide utilization which meant that it was accepted by many others. Money which had these properties greatly facilitated exchange. When the European colonists arrived, they came from many different sea powers, particularly Britain, France, and Spain. The currencies of these countries were used, particularly “pieces of eight” from Spain (http://www.richmondfed.org/about_us/our_tours/money_museum/virtual_tour/colonial_ coin_and_currency/index.cfm ). Even though Britain owned the American colonies, the Spanish currency was adopted because the Spanish colonies were nearby, relatively rich and powerful, and experiencing a great deal of commerce with the colonies which made their currency accessible. The colonies did not have enough of these currencies, and so they issued paper money. Of course, the paper wasn’t worth anything in itself. So the colonies “backed” the currency by making it exchangeable for the foreign currencies. Each state issued its own currency. For example Georgia (http://www.frbsf.org/currency/independence/show.html) had a paper note which was based on the Spanish dollar, even though it had been a British colony. Even after being 2 Chapter 8 - Money in rebellion against Britain other states issued notes that were backed by the English shilling (http://www.frbsf.org/currency/independence/show.html). Strong governments were an important source credibility for a currency, and the states had no illusion that their governments were as strong as those of either Britain or Spain. A strong government that can take necessary actions to back the value of money is essential if people are to believe in the value of money. After winning Independence, the states organized under the Articles of Confederation which preserved the autonomy of the different states. However, the states were not strong enough to inspire much belief in a common currency or their own state currencies. As a result there was a terrible inflation which wiped out the value of the currencies and gave rise to the phrase “not worth a continental” which still today is used to mean that something is worthless. Not until the states were organized under the Constitution under one government would there be a possibility of a strong currency. Particularly when money cases to be valued for its metal content, everyone looks to government for accountability in maintaining the value of the money. But the new government did not issue its own currency. It did not even have its own bank. Private banks, utilities, churches, businesses and charities all issued their own paper money. Bank Note reporters issued books which kept track of those notes which were valuable and those which were “broken.” Continual breakdowns of the money supply occurred and many of the frontier areas were poorly served. It was not until Andrew Jackson’s attack on Biddle’s private bank which had served as the nation’s bank did the United States finally set up its own bank. To discourage issuance of private currencies a 10% surcharge was placed on the creation of notes- effectively creating the first reserve requirement. But it took the civil war before both the Northern and Southern governments issued their own national currencies. The 14th amendment to the constitution would finally end the experiment with private currencies. Why was a national currency so much stronger for the purpose of fighting a war? One reason was seigniorage, the value of being the first to spend the newly created money. But a far more important value of a single currency was the standardization of value. With one currency it was easier for everyone to agree upon its worth, which is key to one of the great values of money as a standard of value. Usability and standardization for money have been the basis of experimentation right up to the present day. Perhaps the greatest innovation was that of the Lydians in standardizing the weight of metal in a coin which could be used for exchange (http://www.richmondfed.org/about_us/our_tours/money_museum/virtual_tour/monies/c oins_of_early_origin/croesus.cfm). This innovation allowed the currency to be used throughout the Mediterranean by many non-Greek states. Rome, Britain, and today United States have experienced the benefits of being the international standardized currency. Today, many countries use the dollar as their currency because it has a widely accepted value. In the face of standardization of a strong international currency, countries have been willing to give up the seigniorage from having their own currency in order to have the economic stability from sharing a commonly valued single currency. 3 Chapter 8 - Money During the Civil War the Union tried seven different experiments in the issuance of money. It issued notes backed by gold, by silver, and by a certain promised interest rate (http://www.richmondfed.org/about_us/our_tours/money_museum/virtual_tour/us_curren cy_1861-1865/index.cfm). But it also tried an experiment in issuing a currency, the United States Note, that was simply backed by government debt. The United States Note (http://www.richmondfed.org/about_us/our_tours/money_museum/virtual_tour/us_curren cy_1861-1865/index.cfm ) would finally become part of the permanent money supply in 1878. It was successful because it could be exchanged for risk-free government bonds which paid a fixed interest rate. The availability of a risk-free bond in which people could store value and actually have it appreciate in value through time was magic to people who were used to the corrupted private system which periodically collapsed and destroyed savings. Long after the gold backed and silver-backed currencies were abolished, the experiment, begun with the United States Note, which was backed only by government debt, won. The Federal Reserve Note that we use today is a direct descendant. Once again the United States experienced a hyperinflation. As it was losing the war, people began to realize that the southern currency would be no good. As always happens with hyperinflation, price increases accelerated until the paper currency was worthless. The failure or even the weakening of government undermines the value of its currency. 2. The Definition of Money The United States was experimenting with the kinds of money that it would use. Economists identify several different types of money, each of which can be used as a medium of exchange: 1. Money based on commodities. The value of such a money is entirely based on a single commodity and that commodity is itself the money as in gold or shells. 2. Fiat money. Fiat money is required by law to be used for exchange purposes. 3. Fiduciary money. Backing money by another currency. This is what we saw the colonies do in early American history when they backed their paper money with the currencies of Spain or Britain. But this is also the idea behind a checking account at a bank. The checking account is "backed" by the American currency. While there are many different ways to exercise buying power, not all of them are money. One of the best examples is the "line of credit" issued by banks. A line of credit is an agreement that a borrower can buy up to a certain limit and the bank will make good in paying for the purchases. Credit cards are a line of credit. But they are not money. They are a loan, not a store of value in themselves, nor a medium of exchange in themselves. The key distinction between a credit card and a debit card is that there is 4 Chapter 8 - Money money already in an account to back the card up, while the credit card is a loan that is backed by nothing but the bank's trust that you'll pay your monthly bill. In the United States there are three basic definitions of money; M1, M2, and M3 and then a final comprehensive category, “L”. These definitions are distinguished on the basis of the liquidity, return, and buying power of the items that are included within each definition. M1 is the most liquid and earns the least return. It includes cash or currency, travelers checks, and transactions accounts. Transactions accounts are characterized by the ability to make direct payments to another party. Each of these items is payable “on demand.” M2 includes M1 but also items which may receive some return. Savings accounts and money market accounts have been increasingly popular over the last twenty years as people have realized the importance of earning a return on money that they have deposited. In some cases, banks or other financial institutions have the authority to restrict the distribution of this form of money in time or in amount. Nevertheless it represents huge amounts of buying power that is used like money. M3 includes M2 but also large categories of buying power that are exercised by institutions, some of which are outside of the country. For example, the Eudollar market consists of dollar accounts in banks outside of the United States. Money is continually being transformed to meet the needs of a changing economy. Before examining the Federal Reserve System it is useful to examine just how much change there has been during our life times in the last twenty years in the United States. The following table shows how each of the items of M3 has changed over the last 20 years. Besides the increased use of money market funds and savings deposits it is possible to see that the use of cash is increasing. Table 8-1. Different Definitions of Money 1980 Percentages 2000 Percentages Currency 115 5.76% 530 7.47% plus travelers checks 3 0.15% 8 0.11% plus Demand deposits 261 13.08% 313 4.41% plus Other checkable deposits 28 1.40% 239 3.37% Equals M1 407 20.40% 1090 15.37% plus Money market funds, retail 64 3.21% 939 13.24% plus savings deposits 400 20.05% 1872 26.40% plus small time deposits 729 36.54% 1046 14.75% Equals M2 1600 80.20% 4947 69.75% plus large time deposits 260 13.03% 827 11.66% plus repurchase agreements 58 2.91% 360 5.08% plus Eurodollars 61 3.06% 191 2.69% Money market funds- institutions only 16 0.80% 767 10.82% Equals M3 1995 100.00% 7092 100.00% *negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) and automatic transfer service (ATS) accounts as well as credit union share and thrift institution demand deposits **less than $100,000 excluding retirement accounts ***$100,000 or more but excluding foreign 5 Chapter 8 - Money 3. The Federal Reserve System Although the U.S. government had unified the currency there were still bank panics, one of the most severe of which occurred in 1907. The Federal Reserve System was created in 1914 to prevent such crises. The Federal Reserve System is the bank for bankers. It is headed by the Board of governors. Each member of that board is appointed to one and only one 14 year term. There are 12 Reserve Banks (and Missouri is the only state with two of those banks) that served different regions of the country. These banks provide the following services for private banks: 1. Clearinghouse for checks. Any bank’s check cashed or deposited at another bank is canceled by the Federal Reserve Bank after transferring funds (reserves) from one bank to the other. That saves banks having to go to each other to collect the money. 2. Reserve accounts. Banks hold their reserves in accounts at the Fed just like we might hold money in a checking account at a bank. In the diagram below, a household might deposit money into a transaction account at Bank A. Then a check could be written for goods and services to a business that has an account at Bank B. After the business deposits the check to the transactions account at Bank B, Bank B sends the check to the Federal Reserve Bank which processes the check by canceling it and transferring reserves from Bank A’s account to Bank B’s account. The canceled check is sent to Bank A who sends it back to the household. Hundreds of billions of dollars are transferred this way each year through the Federal Reserve system. 3. Loans of Reserves. Banks can go to the Fed for loans (“discounts”) of reserves just like we might go to a bank for a loan of money. 4. Cash. The Fed provides cash to the banks in exchange for reserves. Figure 8-1. How the Fed Works FEDERAL RESERVE BANK Bank A A Reserves Bank Bank BankBB Account Account Account Account Canceled check Check BANK A Household account Canceled check BANK B Business account Money Deposited Check Check Household Business Real goods and services 6 Chapter 8 - Money The most important role of the Fed is to control the overall money supply. It does so through three policy instruments: 1. Setting the reserve requirement. The Fed determines the required reserve ratio that each bank must meet. The required reserve ratio (RR) defines how much required reserves (R) a bank must hold to cover its total deposits (transactions accounts (TA)). Reserves include cash at the bank or reserves in the reserve account at the Fed. The formula is: Required Reserves = required reserve ratio X Transactions Accounts R * = RR TA This formula is important because it determines the excess reserves (ER) which determine how much a bank can lend. A bank examines its actual reserves (AR) against its required reserves to determine excess reserves: Excess Reserves = Actual Reserves – Required Reserves ER = AR - R A bank’s ability to make loans is equal to its excess reserves. 2. Determining the Discount Rate. The Fed decides what interest rate to charge banks for borrowing reserves. This “discount rate” sets the floor to all other interest rates. The “Federal Funds rate” is the rate charged by private banks to each other for lending reserves to each other and closely tracks the discount rate. 3. Open Market Operations. The fed buys and sells government debt (bonds, treasuries, etc.) and pays for them with reserves. By buying more government debt, the Fed expands the money supply because the reserves it uses to pay for the bonds then appear as excess reserves to banks which will then lend them out. By selling more government debt, the Fed tightens the money supply. The banks that pay for the bonds will be charged against their reserve accounts with the Fed. With these three instruments the Fed is able to control the money supply. 4. Setting Up a Bank To see how the Fed controls the money supply it is necessary to see how a bank responds to actions by the fed. First we will pretend we are setting up a bank. Then we will see what the bank does in response to different actions by the Fed. 7 Chapter 8 - Money The steps for setting up a bank might include the following: 1. If we were to set up a bank, we would need some equity. Suppose we put up $100,000 (item 1a and we’ll drop three zeroes from now on to make it simpler) with which to (1b) buy the building ($60,000) and (1c) all of the equipment ($40,000) that are needed. The following “T-account” shows how this first action would be recorded in terms of liabilities and equity. Notice that assets and liabilities always balance after every step: Figure 8-2. SETTING UP A NEW BANK AND TAKING DEPOSITS ASSETS LIABILITIES 2b. Reserves at Fed 100 2a. Transactions Account 100 1b. Building 1c. Equipment 1a. Equity TOTAL ASSETS 60 40 200 100 TOTAL LIABILITIES 200 2. Also shown in the above diagram is the effect of advertising for deposits. Everyone hears about our bank and deposits a total of $100,000 in transactions accounts with us (2a). The checks they write on other banks in order to make these deposits cause $100,000 to be transferred to the bank’s reserve account with the Fed (2b). Our accounts now are in balance at $200,000 for both liabilities and assets. 3. The bank must make money. It has three ways that it can invest its reserves. It must leave some of the reserves at the Fed (or equivalently hold the money as cash in its vaults). Here is where the required reserve ratio established by the Fed becomes important. Suppose it is 10%. Then we use the following equation for required reserves to find out how much must be kept in reserves: R = RR* TA = .10 * $100 = $10 This means that the bank has excess reserves given by: 8 Chapter 8 - Money ER = AR - R = 100 - 10 = $90 The bank can purchase securities or loan the money out. Government securities are very safe and they provide a low return. Loans are more risky and provide a much greater return. Suppose the bank decides to buy $40,000 in government bonds and to loan out the rest. To buy the government bonds from the Fed, the bank writes a check on its reserve account, just like we do with a checking account, for $40,000 which leaves $60,000 in reserves (3a) and buys the securities (3b). Then the bank uses the rest ($50,000 ) of its excess reserves to make $50,000 in loans (3c). However, this time it does not have to draw down reserves. It effectively creates MONEY by putting $50,000 into the borrowers’ transactions accounts (3d). When we add the liabilities and assets, everything adds up to the same amount ($250,000) on both sides and it reflects the creation of the new money. Figure 8-3 INVESTING NEW RESERVES ASSETS LIABILITIES 3a. Reserves at Fed 60 3b. Securities 40 3c Loans 50 1b. Building 1c. Equipment 60 40 TOTAL ASSETS 250 2a. Transactions Account 100 3d. Loan adds purchasing power to Transactions Accounts 50 NEWLY CREATED MONEY 1a. Equity 100 TOTAL LIABILITIES 250 The bank has gone “long” by making the choices to buy securities and to make loans. It is “tying up its money” because the money is less liquid even as it is earning more money. Banks are taking on the key role of taking risk and being rewarded by the returns for taking risks. But they are vulnerable to the collapse of the people to whom they lend. They must be very careful about the willingness and ability of borrowers to pay funds back and so they do careful credit checks and often make assessments of the character of the people to whom they lend. 9 Chapter 8 - Money 4 But the bank doesn’t hold onto the new money for long. The borrowers have not spent the money they have borrowed. When they write a check for $50,000 it must be subtracted from the transactions account (4a) and the Fed will transfer $50,000 of the bank’s reserves to some other bank leaving only $10,000 in reserves (4b). Now total assets and liabilities are exactly where they were before the loan and the purchase of securities. However, the created money has not disappeared. It has now gone to another bank where it will provide the basis for a new loan. Figure 8-4 THE BORROWER DRAWS DOWN THE LOAN ASSETS LIABILITIES 3a. Reserves at Fed 60 4b. Subtracted when Fed transfers reserves to another bank -50 3b. Securities 40 3c Loans 50 2a. Transactions Account 100 3d. added by loan 50 4a. Subtracted when borrower spends -50 1b. Building 1c. Equipment 1a. Equity TOTAL ASSETS 60 40 200 100 TOTAL LIABILITIES 200 . Now that we have set up a bank, let’s see how the Fed can alter the money supply 5. Changing the Reserve Requirement The Fed can change the required reserve ratio (RR). Suppose the Fed lowers the ratio. Let’s work through what our new bank will do, assuming that it will lend all new excess reserves that it receives. Following is where we left our new bank. We can follow the effect of cutting the reserve ratio from 10% to 5%. 1. The bank computes its required reserves: R = RR* TA = .05 * $100 = $5 This means that the bank has excess reserves given by: 10 Chapter 8 - Money ER = AR - R = 10 - 5 = $5 The bank uses the $5,000 of its excess reserves to make $5,000 in loans (1a). It effectively creates MONEY by putting $5,000 into the borrowers’ transactions accounts (1b). When we add the liabilities and assets, everything adds up to the same amount ($205,000) on both sides and it reflects the creation of the new money. 2 Once again the bank doesn’t hold onto the new money for long. The borrowers have not spent the money they have borrowed. When they write a check for $5,000 it must be subtracted from the transactions account (2a) and the Fed will transfer $5,000 of the bank’s reserves to some other bank leaving only $5,000 in reserves (2b). Now total assets and liabilities are exactly where they were before the loan and the purchase of securities. However, the created money has not disappeared. It has now gone to another bank where it will provide the basis for a new loan. Figure 8-5. CHANGING THE RESERVE REQUIREMENT ASSETS LIABILITIES Reserves at Fed 10 2a. Reserve drawn down -5 Securities 40 Loans 1a new loans 50 5 Building Equipment 60 40 TOTAL ASSETS 200 Transactions Account 100 1b loan adds money to transactions accounts 5 2b. Borrower writes check on account -5 Equity 100 TOTAL LIABILITIES 200 The above example involves "loosening" the money supply. When the fed tightens the money supply, banks suddenly find themselves out of compliance with the reserve requirement. They can get back into compliance with the required reserves by allowing borrowers to pay off loans. The effect of paying off a loan is to lower loans by the same amount as reserves are increased. In effect letting people pay off loans rather than making new loans means that the bank is “going short.” Because this mechanism is 11 Chapter 8 - Money so powerful in creating and destroying money Congress is very reluctant to let the Fed use this instrument, and historically it has been used very infrequently. 6. Open Market Operations By far the most commonly used mechanism for controlling the money supply is the use of open market operations. For this purpose, the Fed buys or sells government securities to a bank. Let’s see what happens to our new bank where we left it in the previous section. Suppose the Fed buys $10,000 worth of government securities from the bank. The following steps occur: Figure 8-6. OPEN MARKET OPERATIONS ASSETS 1b. 3b. 1a. 2a. LIABILITIES Reserves at Fed 5 FED pays reserves +10 FED transfers reserves to another bank -10 Securities 40 Bank sells securities -10 Loans 55 Bank makes loans 10 Building Equipment TOTAL ASSETS 60 40 200 Transactions Account 100 2b. Bank adds money to transactions account 10 3a. Borrower draws down loan -10 Equity 100 TOTAL LIABILITIES 200 1. The bank sells $10,000 worth of government securities (1a) and the Fed pays $10,000 worth of reserves (1b). 2. The bank recomputes its required reserves: R = RR* TA = .05 * $100 = $5 This means that the bank has excess reserves given by: 12 Chapter 8 - Money ER = AR - R = 15 - 5 = $10 The bank uses the $10,000 of its excess reserves to make $10,000 in loans (2a). It effectively creates MONEY by putting $10,000 into the borrowers’ transactions accounts (2b). When we add the liabilities and assets, everything adds up to the same amount ($210,000) on both sides and it reflects the creation of the new money. 3 Once again the bank doesn’t hold onto the new money for long. The borrowers have not spent the money they have borrowed. When they write a check for $10,000 it must be subtracted from the transactions account (3a) and the Fed will transfer $10,000 of the bank’s reserves to some other bank leaving only $5,000 in reserves (3b). Now total assets and liabilities are exactly where they were before the loan and the purchase of securities. However, the created money has not disappeared. It has now gone to another bank where it will provide the basis for a new loan. The open market operations of the Fed work in reverse when monetary policy is tightened. Then the Fed sells government securities to banks and the banks use their reserves to pay for the securities. An example of a bank buying securities was provided when we first set up the bank. 7. Discounting Occasionally banks have a shortage of reserves. They can make up the reserve shortage by selling securities, borrowing funds from other banks through a market referred to as the "federal funds market," or they can borrow reserves from the Fed at the "discount" window. Discounts are the Fed's loans of reserves to banks and those loans are made at the discount rate. When the Fed wants to discourage expansion of the money supply, it can raise the discount rate and make it more expensive for banks to borrow reserves from the Fed. And if the banks then try to go to the Federal Funds market to borrow from other banks they will find that the "federal funds rate" has followed the discount rate upward. So, even if the Fed doesn't lend much reserves itself, it has a big impact on overall lending of reserves. We can follow our bank from the end of last section as it borrows reserves from the Fed in order to make new loans: 1. Suppose the bank wants to borrow $15 worth of reserves. The discounts from the Fed are payable back to the Fed and must be shown on the liability side of a bank's ledger (1a). The borrowed reserves are added to total reserves (1b). 2. The bank recomputes its required reserves: 13 Chapter 8 - Money R = RR* TA = .05 * $100 = $5 This means that the bank has excess reserves given by: ER = AR - R = 20 - 5 = $15 The bank uses the $15,000 of its excess reserves to make $15,000 in loans (2a). It effectively creates MONEY by putting $15,000 into the borrowers’ transactions accounts (2b). When we add the liabilities and assets, everything adds up to the same amount ($230,000) on both sides and it reflects the creation of the new money. Figure 8-7. DISCOUNTING ASSETS LIABILITIES Reserves at Fed 5 1b. Reserves from Fed 15 3b. FED transfers reserves to another bank -15 Securities 30 Loans 65 2a. Bank makes loans 15 Building Equipment TOTAL ASSETS Transactions Account 100 2b. Bank adds money to transactions account 15 3a. Borrower draws down loan -15 1a. Discounts 15 Equity 100 60 40 215 TOTAL LIABILITIES 215 3 Once again the bank doesn’t hold onto the new money for long. The borrowers have not spent the money they have borrowed. When they write a check for $15,000 it must be subtracted from the transactions account (3a) and the Fed will transfer $15,000 of the bank’s reserves to some other bank leaving only $5,000 in reserves (3b). Now total assets and liabilities are larger by the amount of reserves lent by the Fed. $15,000 of the newly created money has now gone to another bank where it will provide the basis for a new loan. 14 Chapter 8 - Money As in the previous two instruments used by the Fed, much of the effect of Fed actions is repetitive. And the overall impact on the economy of the Fed's action on any given bank is similarly repetitive. 8. Money Multiplier Through the Entire Banking System Each of the actions that the Fed took above can be analyzed from the point of view of the entire Federal Reserve System of Banks. If we step back and look at the Taccounts of the entire banking system it operates quite similarly to the individual bank. However the entire system never loses any reserves. If every transaction stays within a system it is called a monopoly banking system. The reserves never are transferred outside of such system. That means that when a check is written the reserves always stay the same for the entire banking system. The multiplying effects of each successive bank receiving higher transactions deposits from the original infusion (or contraction) of reserves leads to an expansion of loans. To see how this occurs let's reexamine the case of the changing reserve requirement on the bank that was created in section 5. That bank lent $5,000 as a result of the changing reserve requirement which added the same amount to its transaction deposits. When those deposits were drawn down by the borrower, they went to someone else who then deposited the $5,000 at another bank. That other bank, call it "bank B" also had a required reserve ratio of .05. So out of its $5000 of new deposits its required reserves would be: R = RR* TA = .05 * $5 = $.25 This means that the bank has excess reserves given by: ER = AR - R = 5 - .25 = 4.75 When Bank B lends $4.75, the money ends up as greater deposits in a bank C, which then computes its required and excess reserves. The result can be summarized by an EXCEL program as follows: 15 Chapter 8 - Money Table 8-2. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 A Bank Initial Bank Bank B Bank C Bank D Bank E Bank F B New Deposit C |D Excess Reserves | RR= 5 0.05 5 4.75 4.75 4.5125 4.5125 4.286875 4.286875 4.07253125 4.07253125 3.868904688 … … Total is new created money 100 | NOTE: In this program, the new “$5” deposit of bank B (shown in B3) equals the excess reserves of the initial bank (shown in C2). New deposits of bank B are then multiplied by (1- RR) where RR, the reserve requirement, is posted at the upper right hand corner in D2. In other words, C3 =B3*(1-D2). Dragging down both formulas (from B3 and then from C3) shows in the third column how much money is created by each bank. The total, if dragged on forever would approach 100. In a monopoly system, the existence of excess reserves anywhere is multiplied by the money multiplier to find the total expansion of loans that will occur throughout the system. The arm waving of the previous paragraph is summarized by the formula: New money created = (Initial excess reserves)/RR = 5/.05 = 100 To illustrate how a monopoly banking system is different from a single bank, we will use exactly the same numbers as we did in section 5 and pretend that they represent a trillion dollars rather than only a thousand dollars. Here is the way the overall system looks and the step by step procedure for analyzing the effect of cutting the reserve requirement from .10 to .05. 1. The monopoly bank computes its required reserves, just like an individual bank would: R = RR* TA = .05 * $100 = $5 This means that the bank has excess reserves given by: ER = AR - R = 10 - 5 = $5 16 Chapter 8 - Money But the monopoly bank uses the $5 trillion of its excess reserves to make loans in the amount of the excess reserves times the money multiplier, 1/.05. That's the same thing as dividing the excess reserves by the required reserve ratio: Loans = ER * (1/.05) = 5/.05 =100 After all multiplying effects the banking system has added $100 trillion to loans(1a). It effectively creates MONEY by putting $100 trillion into the borrowers’ transactions accounts (1b). When we add the liabilities and assets, everything adds up to the original total plus the amount of the new loans. 2 Since the reserves stay within the system, we don't have a second step- unlike an individual bank. Unlike the inidividual bank we can see the complete multiplying effect of the money multiplier in the T-account of a monopoly banking system. Figure 8-8. CHANGING THE RESERVE REQUIREMENT FOR A MONOPOLY BANKING SYSTEM ASSETS LIABILITIES Reserves at Fed 10 Securities 40 Loans 1a new loans 50 100 Building Equipment 60 40 TOTAL ASSETS 300 Transactions Account 100 1b loan adds money to transactions accounts 100 Equity 100 TOTAL LIABILITIES 300 9. Conclusion Like real goods, money has a multiplier. While the flow of goods and services is amplified by a multiplier that depends upon the marginal propensity to consume, the flow of money is amplified by a multiplier that depends upon the required reserve ratio which tells banks how much money they must keep on hand. Both the flow of real goods and the flow of money are regulated by how much of the flow is siphoned off, either by government requirement or people's behavior in saving. 17 Chapter 8 - Money From a management point of view, the two multipliers must be kept in synchronization with each other. A fundamental identity, called the quantity theory of money, connects money (M) and the real goods (real GDP) through the price level (P) and the velocity of money (V): M*V= P*(real GDP) In effect, the equation shows that prices and the velocity of money must always change to maintain the identity. The government must manage (or avoid overmanaging) the money supply in order to prevent hyperinflations or deflations (either of which cause P to spin out of control) as well as to prevent shut downs or overheating of the economy (where real GDP spins out of control). With the lags in our information about real GDP, finding the right balance is a continual experiment with dire consequences when there is failure. Crucial to the working of the monetary system is the role of the Banks in creating money. While the government can print cash, the real buying power comes from the bankers' roles in lending money. They will only lend money if they trust people will pay it back with interest. When such trust is violated, bankers cease making loans. Without loans businesses begin to shut down. Without such trust money, you have now learned how to use the T-accounts to see how money simply evaporates- no one steals it. Every loan that is created is a vote of faith in a sustained economy and is itself sustaining of the economy. Case Study: China’s Central Bank. The following article from the New York Times shows that China is trying to use its monetary policy to control growth, much as the Federal Reserve System does in the United States. However, with only recent experience in making loans, China’s banks have a likelihood of making many bad loans as the following article shows: China's Soft Landing Published: June 11, 2004 It's not all up to Alan Greenspan. When it comes to the global economy, Zhou Xiaochuan and Liu Mingkang may be as influential, even if most Americans have never heard of them. Mr. Zhou, the governor of China's central bank, and Mr. Liu, its top banking regulator, are central to the country's efforts to cool its overheated economy. China, the world's most populous nation, has been growing at a torrid pace for some time, and there is a gold-rush aspect to its boom that Beijing needs to address. The aim is to achieve what economists call a soft landing, turning that headlong rush into continued, sustainable growth. The alternative is a hard landing, also known as a crash. More than the recent dot-com bubble, China's boom resembles America's feverish industrialization of the late 19th century. Much as the United States did then, China has a dynamic economy that lacks a developed financial system. If it's serious about its 18 Chapter 8 - Money ambitions, the Communist government will need to foster the creation of mature and independent capital markets, even though it would mean relinquishing more control. China has averaged 10 percent annual growth in recent years, lifting millions out of poverty. The arithmetic of the boom is staggering. Ten million Chinese enter the work force each year, and some 350 million people are expected to migrate from the countryside to cities in the next quarter-century. China's exports have doubled in less than five years, though the country's growing appetite for commodities to fuel its industrialization means that it has an American-size trade deficit. The market for mortgage loans grew by a staggering 40 percent last year. Spending on new steel mills tripled from 2002 to 2003, and China now consumes nearly 30 percent of the world's steel products. Much of the exuberance is rational, but plenty is not. In a frothy environment where money is in ample supply, and where assessing credit risks remains a sketchy concept, the banking system may have to write off more than a third of its outstanding loans. Part of the soft-landing strategy of Mr. Liu and Mr. Zhou is to make the banks more parsimonious. Beijing was hoping to push its growth rate down near the 7 percent mark this year, but the economy still grew at an annual rate of 9.7 percent in the first quarter…, China is now one of the world's twin economic engines, alongside the United States. China's growing appetite for everything from soybeans to iron ore is responsible for an across-the-board surge in commodity prices. And not only is the Chinese market helping to perk up Japan and South Korea, but it has also become important to such faraway nations as Brazil. The whole world, in other words, is anxiously watching to see whether China remains the next big thing or becomes the next big bust. accessed on June 11, 2004 from the New York Times at: http://www.nytimes.com/2004/06/11/opinion/11FRI3.html?th If Chinese banks experience large defaults on loans, what will happen to their money supply? Based on the model of the banking system in this chapter you should be able to see that there will be a collapse in the ability of the banks to make loans. With fewer loans, by definition the money supply must contract. There will be lower output and fewer jobs. "discount" window .... 14 Fiat money .................. 4 Discount Rate .............. 8 Discounting ............... 14 Discounts................... 14 excess reserves .......... 11 federal funds market . 14 federal funds rate....... 14 Federal Reserve System ................................. 6 Fiduciary money ......... 4 going short ................ 12 gone “long” ............... 10 Copyright loosening" the money supply .................... 12 M*V= P*(real GDP) . 18 M1 ............................... 5 M2 ............................... 5 M3 ............................... 5 medium of exchange ... 2 money multiplier ....... 17 Money Multiplier ...... 15 monopoly banking system ................... 15 Open Market Operations ................................. 8 required reserves ....... 13 reserve requirement ..... 7 Reserve Requirement 11 seigniorage .................. 3 shortage of reserves... 14 standard of value ......... 3 store value ................... 4 T-account .................. 17 the quantity theory of money.................... 18 transactions accounts 9 velocity of money ..... 18 19