CHAPTER 7. THE MACROECONOMY THROUGH AGGREGATE DEMAND AND SUPPLY

advertisement

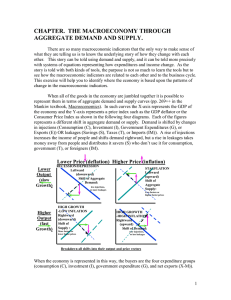

CHAPTER 7. THE MACROECONOMY THROUGH AGGREGATE DEMAND AND SUPPLY A. Aggregate Demand and Supply ................................................................................ 1 Figure 1a. Shifts of Aggregate Demand and Supply .............................................. 2 B. The Disequilibrium Measures ................................................................................... 2 FIGURE 1b. RIGHTWARD SHIFT OF AGGREGATE DEMAND ................. 3 C. Price Responses to Disequilibrium ........................................................................... 4 D. Impacts of Income Changes on Federal Deficits ...................................................... 5 FIGURE 2 Behavioral Response of Expenditues to Income ................................. 6 E. Impacts of Income on Exports, Imports and the Trade Deficit ................................. 7 F. The Injection-Leakage Identity.................................................................................. 7 Figure 3. The GRAND MACRO DESIGN ............................................................. 8 G. Consumption and Income Through Time ................................................................. 8 FIGURE 4. CONSUMPTION AND INCOME ..................................................... 9 H. The Business Cycle ................................................................................................... 9 Figure 5. Low Prices Stimulate the Economy and then Rise to Cut it Off ....... 11 Figure 6. High Prices Cut Off the Economy and then Fall with it .................... 12 I. Finding your own Barometric Indicators of the Economy ....................................... 12 There are so many macroeconomic indicators that the only way to make sense of what they are telling us is to know the underlying story of how they change with each other. This story can be told using demand and supply, and it can be told more precisely with systems of equations representing how expenditures and income change. As the story is told with both kinds of tools, the purpose is not so much to learn the tools but to see how the macroeconomic indicators are related to each other and to the business cycle. This exercise will help you to identify where the economy is based upon the patterns of change in the macroeconomic indicators. A. Aggregate Demand and Supply The economy can be represented with by one aggregate demand curve and one aggregate supply curve. When all of the goods in the economy are jumbled together in this way, the X-axis represents the disposable income (Y) of the economy and the Y-axis represents a price index such as the GDP deflator or the Consumer Price Index. When the economy is represented in this way, the buyers are the four expenditure groups (consumption (C), investment (I), government expenditure (G), and net exports (X-M)). Any determinant of demand that affects these four expenditure groups causes the aggregate demand curve to shift. For example, increased saving (S) and/or increased taxes (T) both lower consumption and therefore affects the aggregate demand curve. Figure 1 shows the basic shifts in demand, based on the changes in injections (C,I,G,X) and the changes in leakages (S,T,M). 1 Figure 1a. Shifts of Aggregate Demand and Supply In this diagram we have changed the Y-axis to be the inflation rate (i.e. the percentage change in prices) and the X-axis to be the Growth rate (i.e. the percentage change in disposable income), rather than the levels of prices and quantities respectively. The Aggregate Supply curve measures the capacity of the economy to produce different levels of GDP. We are going to assume that we are looking at only one year and that the economy has the flexibility to produce more GDP at higher prices. While many economists believe that the aggregate supply curve is essentially vertical in the long run (so that the capacity of the economy is not very responsive to higher prices), we can assume here that some additional capacity can be made available if prices are high enough. If it is not constrained from growing the aggregate supply curve shifts as more resources are made available. So as more labor (L), Land (N), Capital (K), or entrepreneurial skill (En) are created, the aggregate supply curve shifts to the right. It also shifts if factor payments increase. So, holding inflation constant, if the wage bill rises, profits rise, rents rise, or interest payments rise, the aggregate supply curve will be shifting to the right. In other words more factor income has been made available, coaxing out a greater availability of the factor of production. B. The Disequilibrium Measures Let’s see what happens to the economy when consumers suddenly become optimistic about the economy and start spending more money. They might finance this 2 consumption by going into debt in their credit cards. While the increased debt does not affect aggregate demand or supply, the increased consumption shifts the demand curve to the right as shown in Figure 1. However, the initial shift does not become immediately visible to businesses or the government. Instead inventories begin to disappear a little faster than usual at the current prices. If businesses don’t recognize this change in inventory very quickly and leave prices unchanged, shortages will begin to develop, lines will form, and people will resell the product to those who are willing to pay more- very much like scalpers do with tickets at sports events. Even if businesses do recognize this change in inventory quickly there may be lags in how quickly they can hire more workers (unemployment will be high) and expand capacity (production capacity will be low) to increase production. The recognition lag and slowness in responding means that orders are beginning to be stacked up and backlogged. Companies are beginning to increase capacity utilization to fill their orders so that customers will continue to be loyal. FIGURE 1b. RIGHTWARD SHIFT OF AGGREGATE DEMAND CPI index Aggregate Demand Greater Price (inflation) Greater quantity Aggregate Supply Disposable Income (Y) The first chapter of the story of the business cycle is a sudden change across the economy of the disequilibrium measures as shown in the following summary: Upside of the Cycle Change in inventories Change in orders Change in capacity utilization Direction of indicator + + For each of our disequilibrium indicators we are interested in the change of the indicator, not the level of the indicator. Good media summaries about the economy should not only 3 compare the level of these indicators with previous periods, but should compare the change in these indicators to past trends of change in the indicators. C. Price Responses to Disequilibrium As capacity utilization reaches to 100% and inventories fall toward zero, markets will see higher prices as indicated in Figure 1. Even if manufacturers do not raise the prices the middlemen will. Wholesalers and retailers who are close to the customer will see the surge in aggregate demand and will recognize the opportunities available in the market place to charge higher prices and they will charge the higher prices. By doing so, they are rationing the product. Some people will no longer vie for goods and services at the higher prices while those who are willing to pay the higher prices will receive the goods and services. The Bureau of Labor Statistics in its monthly surveys of retailers will discover and record the higher prices in the Consumer Price Index. The media will report with lags of one to two months the percentage change in the Index and should record a percentage change that is higher than past trends. Their articles will lament the increase in the inflation rate, which is measured by the percentage change in the Consumer Price Index. The Consumer Price Index automatically triggers rises in social security payments and cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) clauses in contracts- although it may take a year for these changes to occur. Labor unions will look at rises in the cost of living and will use them to negotiate higher wages in their contracts. These wage increases will take as much three to five years to be reflected (depending upon how frequently a contract is renegotiated). However, in the much larger non-unionized sector of the economy, wages will also rise. The demand for labor is derived from the demand for the goods and services that they produce. When demand in the product market shifts, the demand in the labor market shifts in the same direction. The illustration of the higher demand for labor would appear exactly as in Figure 1, except that the X-axis would be labor and the Y-axis would be wages. A much faster adjustment to higher inflation rates can occur in interest rates. When businesses recognize that aggregate demand is rising for their goods, they suddenly want to expand their businesses. Often the fastest way to undertake the necessary additional gross investment is to borrow from the bank. Banks notice the increased demand for money. Since the price of borrowing is the interest rate, the increased demand for money leads to a rise in the interest rate. The illustration of the higher demand for money would appear exactly as in Figure 1, except that the X-axis would be money and the Y-axis would be interest rates. Exchange rates can moderate the impacts of the business cycle. If inflation is worsening with higher prices, wages, and interest rates a strengthening dollar actually permits people to import goods which can ease any shortages that might be occurring at home. Furthermore, since goods and services abroad are cheaper when a domestic currency strengthens, there is a moderating influence on inflation; domestic businesses can’t raise their prices too far without losing markets to foreign producers. However, if an economy is running large trade deficits due to the economy’s growth, then the 4 exchange rate may fall in value. In this case foreign markets don’t provide as much of a moderating influence. In fact interest rates may have to rise higher to offset the falling value of the currency so that foreign investors won’t lose money by investing in the United States. Upside of the Cycle Direction of indicator Inflation (percentage change in prices) + Change in wages + Change in interest rates + Change in value of domestic currency D. Impacts of Income Changes on Federal Deficits The National Accounts would now reflect the effects of the business cycle, but preparing and reporting the information takes time and the media will be reporting the changes in the economy months after those changes have occurred. It takes up to two years before the final revisions of the data may be available on the national accounts. So it may be possible only to guess where the economy is based upon disequilibrium and price measures. Nevertheless, once we have an educated guess about how much disposable income is changing it is possible to predict what is happening to the rest of the items in the accounts. Figure 2 shows how the injections and leakages of the economy are related to disposable income. 5 FIGURE 2 Behavioral Response of Expenditures to Income BEHAVIORAL RESPONSE OF EXPENDITURES TO INCOME Imports Taxes Federal Surplus Federal Deficit Saving Unintended Inventory Increase Trade Deficit Investment Exports Government Expenditures D. Income Trade Surplus D. Income Unintended Inventory Decrease D. Income In the first diagram of Figure 2, government expenditures are examined with respect to changes in disposable income (on the X-axis). With higher income the diagram shows: Taxes should be rising, particularly income taxes Government expenditures may even fall because there are less social services needed because there are fewer people unemployed or on welfare. Since the federal deficit is the difference between government taxes and government expenditures, the deficit decreases or even becomes a surplus as income rises. While the president of the United States often receives the blame for federal deficits, the state of the economy may be much more important, particularly in the first two years of administration. However, historically some presidents have been able to make a substantial change in expenditures or taxes in their first years, as did Franklin Roosevelt, Ronald Reagan, and, most recently, George Bush and Barack Obama in their tax cuts. In these cases, the government expenditure and tax curves actually shift and change the income level at which a deficit turns into a federal surplus. By the way, it’s not just the federal government that works this way. Most of the state and local governments are thrown into serious potential deficits when an economy goes into recession which forces 6 serious and sudden expenditure cutbacks Particularly if their laws require them to balance the budget every year. E. Impacts of Income on Exports, Imports and the Trade Deficit In the second diagram of Figure 2, exports and imports are examined with respect to changes in disposable income (on the X-axis). With higher income the diagram shows: Imports should be rising, as people buy more foreign imports. Exports don’t change with domestic income, although they would shift with foreign income which would affect how much foreigners would buy of American goods. But only domestic income is shown on the X-axis. Since the balance of trade (which is the same thing as net exports) is the difference between exports and imports, the trade surplus decreases or becomes a deficit as income rises. As the economy grows; the trade balance worsens! In other words the economy always faces a fundamental tradeoff between the federal deficit and the trade balance as income changes; one gets better at the expense of the other. F. The Injection-Leakage Identity Since injections (Investment(I) + Government Expenditures(G) + Exports (X)) in the economy must equal the leakages (Savings (S) + Taxes (T) + Imports (IMP)) from the economy, the following identity must hold: I + G + X = S + T +IMP But we can write this equation in terms of the fundamental balances: 7 FIGURE 3. The GRAND MACRO DESIGN Injections Leakages Balance Consumption Consumption 0 Exports - Imports = Trade Balance Govt. Expenditures - Taxes = Federal Balance Investment Savings ___________________________________________________ E+G+I = Imp + T + S Which means: X-M (Trade Balance)= T- G (Federal Balance) + S-I Savings and investment serve a balancing role. As shown in the last diagram of Figure 2, there is an equilibrium disposable income level at which savings and investment perfectly balance. But if disposable income falls below this equilibrium, savings will be below investment and inventories will quickly drop below desirable levels. When inventories drop below desired levels, economists say there is “involuntary disinvestment” or “involuntary declines in inventory” in the economy. To avoid such disinvestments, businesses will try to produce more output and increase their capacity to produce more output. In effect they are increasing investment which will stimulate the economy to grow. This increase in investment will further shift aggregate demand as shown in Figure 1. G. Consumption and Income Through Time As disposable income grows, consumption will also grow. Consumption (C) is very closely related to income (Y). Figure 4 shows this relationship over the last thirty years. 8 FIGURE 4. CONSUMPTION AND INCOME When this relationship is shown logarithmically (lower diagram), the relationship between the two is clearly constant. Notice how different our conclusions are about the growth rate of the economy with the two diagrams in Figure 3. The logarithmic presentation of the data clearly shows the slowing down of the economy while the raw data (upper diagram) suggests that growth is accelerating. The behavior relationship between disposable income (Y) and personal consumption (C) is so close it is commonly represented as the following consumption function: C= a + b* Y The “a” refers to “autonomous consumption.” That is the component of consumption that is not sensitive to income. In other words, no matter how low income might be, there is a certain level of consumption that people will have. The “b” coefficient is referred to as the “marginal propensity to consume (MPC)”. The marginal propensity to consume shows how much of each extra dollar that is earned will be spent on consumption, rather than saving. In other words people, have a choice to spend their income for consumption today or consumption in the future (saving). The marginal propensity to save is simply 1-MPC. H. The Business Cycle We have now found several simultaneous indicators which are relied upon to verify where we are in the business cycle. Each of these indicators is dependent upon income: 9 Upside of the Cycle Income, Output, Expenditure measures Government Deficit Trade surplus Consumption, Saving Imports Taxes Direction of indicator + + + + + + There are many lagging indicators of the economy. Perhaps the most important of these is unemployment and other measures of human resource utilization. When businesses see inventories falling too quickly and the opportunity to sell more of their output, they would like to hire more workers. But they may not be very certain that the economy really is expanding. So they will first attempt to meet the greater needs for workers by paying more overtime to their workers and expanding the number of average hours worked by employees. In this way they can avoid hiring new workers who might prove expensive to train and to let go if growth should fizzle. However, this expedient can rapidly create morale problems and higher wage demands. Within months of a growth surge in the economy, businesses will begin serious new hiring. Unfortunately finding the right people may take a long time. It may be six months to several years before companies are able to hire enough people to meet the new growth needs adequately. The labor sector of the economy typically lags the economy. Upside of the Cycle Change in Average hours worked per week Change in overtime hours Changes in unemployment rate Changes in employment Direction of indicator + + + + Many indicators serve a dual role of both reflecting and regulating the economy. Prices are by far the most important example of such indicators. The following diagram summarizes the dual role of prices as it stimulates the economy and then curbs its growth: 10 FIGURE 5. Low Prices Stimulate the Economy and then Rise to Cut it Off GDP Government. Balance Unemployment Trade Balance Inventory Change 6 mos. Prices, Wages, Interest rates Exchange rates 1 to 2 years Prices, Wages, Interest rates Exchange rates When prices are low as represented at the left of this diagram, workers are desperate to work and receive low wages, banks have no one to lend to, and inflation rates are low; these are perfect conditions for new businesses to get started. Their entry into the market stimulates income and the GDP which pushes the government toward surplus, lowers the unemployment rate (dotted lines indicate inverse relationships between two variables), pushes the trade balance toward deficit, and leads to rapid turnover of inventory. Within half a year or more prices will begin to follow the economy upward. But the upward rise of prices is the same thing as inflation. Interest rates start to rise and COLAs pull up wage rates. The greater trade deficits will eventually weaken the dollar exchange rate and make foreign prices higher. Now prices begin to work against the economy as summarized in the following diagram: 11 FIGURE 6. High Prices Cut Off the Economy and then Fall with it Prices, Wages, Interest rates Exchange rates 1 to 2 years GDP Government. Balance Unemployment Trade Balance Inventory Change 6 mos. Prices, Wages, Interest rates Exchange rates As the prices, wages, and interest rates rise, they begin to shut down the economy. As wages catch up to an initial surge in price increases, profit margins are squeezed, possibly even worse than if prices had never risen at all. As buyers close their pocket books to more increases, businesses go bankrupt. The economy may enter a period of stagflation where inflation is growing but the growth rate is falling and unemployment, the federal deficit, and inventories are becoming worse. Prices are working like a thermostat to shut the economy down. Prices, wages, and interest rates therefore reflect where the economy has been, but also where it is going. Rising prices mean the economy for the last couple of months has likely been growing, but accelerating price increases is likely to indicate that the economy within the next year or two is likely to be experience slower and possibly negative growth rates. I. Finding your own Barometric Indicators of the Economy There are many indicators of the economy such as the stock market, money supply, government debt, private debt, etc. which have not been covered. It is much more important for you to develop your own indicators for barometric forecasting. Most published data are not reported quickly enough to indicate the changes that are occurring to the economy. We can get much better information by simply watching the environment around us. Here are some of the items that are particularly useful to look for: (1) Gasoline Prices. Pick one service station that you pass every day and simply observe the price of gasoline. Whenever the economy is booming transportation services are being used by everyone and the increased demand of all goods and services is anticipated by the oil industry in light of fixed supplies of oil and is therefore an early 12 warning of what is happening to the economy. Many industries like the auto and airplane industries are likely to be doing as well oil because they are complementary goods to oil. (2) Housing Sales. As you become familiar with a neighborhood, you will begin to get a sense of how long it takes for houses to move. If “for sale” signs are up for a long time or there are relatively few houses being sold, it may mean that the real estate market is slowing down. If you watch find out the prices of the houses that sell, you may be able to judge how fast housing prices are rising which helps to understand inflation rates as well as to indicate rising incomes of people. A strong housing market pulls the rest of the economy along including the construction industry, construction materials, furniture, gardening items, and a wide range of services. (3) Malls. If you regularly frequent a mall you may be able to judge when a mall is experiencing above normal or below normal traffic in the stores. You may also see evidence such as vacant store fronts or larger than normal sales that indicate economic troubles. Malls provide a particularly broad summary of economic activity of the economy. (4) Advertising in the Media. Events like the superbowl and NASCAR races are extremely expensive advertising opportunities. Changes in who is buying the top advertising spots or who is sponsoring major events may indicate important changes in what industries are doing well in the economy. At the other extreme the want ads sections of the newspaper provides insights into the tightness of the job market, the health of the used goods sectors of the market, and the overall amount of economic activity. (5) New Construction Activity. Coming into a city for a trip can often indicate the health of the city as well as the health of the economy. Busy construction cranes, newly cleared land, full parking lots, shuttered buildings, dilapidated store fronts, maintenance levels of streets, cleanliness of sidewalks, and a wide number of other visual clues can provide information about how an economy is faring. These are only a few ideas of what is easily available on a daily basis to give you clues about the economy. You may find your own indicators that are much more useful to you as early warnings of what may be happening to the economy. INDEX aggregate demand curve, 1 Aggregate Supply, 2 balance of trade, 7 cost-of-living adjustment (COLA), 4 Exchange rates, 4 Exports, 7 federal deficit, 6 federal surplus, 6 Government expenditures, 6 Imports, 7 inflation rate, 4 Injection-Leakage Identity, 7 injections, 7 interest rates, 4 inventories, 3 leakages, 7 net exports, 7 production capacity, 3 shortages, 3 stagflation, 12 Taxes, 6 unemployment, 3 wages, 4 copyright 13