Development as Discourse

advertisement

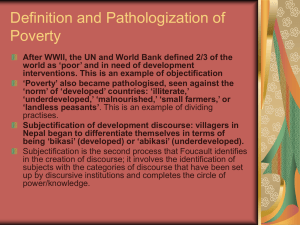

Development as Discourse ‘The metaphor of development gave global hegemony to a purely Western genealogy of history, robbing peoples of different cultures of the opportunity to define the forms of their social life.’ Critics of ‘Development’, such as Esteva, see it as giving hegemony to a western conception of history and society. What is the history of the term development? o Historically, development until about 150 years ago described a process through which the potentials of an organism are released until it reaches its complete, full-fledged form. o Between 1760 and 1850, the meaning changed from a concept of change and transformation towards an appropriate form of ‘maturity’ to a meaning in which there emerged an ever more perfect form. o At the same time, it became connected to the concept of progress, which was related to economic notions of what progress meant. o Progress was linked to colonialism and to the justification for European countries politically and economically controlling other societies, or, in French terms, to ‘la mission civilatrice’. o As colonialism waned through movements for political independence from the 1940s to the 1960s, the term development became key, while that of progress was discredited and became secondary. o 1948: Harry Truman defined the 20th century as the century of ‘development’. 50 Years of Development: Its Historical Context After World War II, the US emerged as the major centre of capital accumulation. US needed to find markets for its goods, to invest surplus capital abroad, to secure control over raw materials, e.g. oil, and to establish a network of military power that would be predominant and ideally, unchallenged. This was the same period in which development discourse was put in place, especially through the creation of international institutions that regulated and defined ‘development’: These included not only various aid agencies of the US and allied governments, but also international financial institutions such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, created through the Bretton Woods agreement in 1944. Goal was rhetorically ‘the eradication of poverty’. 50 years later, poverty has not been eradicated, but has proliferated and relative poverty has increased massively. Obviously some disconnect between rhetoric and reality here. Different explanations are given for this: o Foucault: Development is a discourse, i.e. a combination of knowledge and power, supported by influential and powerful institutions that disseminate their worldviews. o Marxian/Gramscian view: Development is rhetoric, ideology or hegemony, an unconscious mask that its practitioners believe in, but what development is really about the introduction and growth of capitalism in regions of the world that had very different societies, cultures and production systems. Cammock: World Bank prescriptions for development mirror the early stages of capitalism that England first went through in the late 18 th and early 19th centuries. Development as Discourse Discourse: a combination of knowledge and power that presents itself as pure, value-free and objective knowledge. Value-free and objective knowledge is a result of the emergence of modernity, a world view emanating first from Europe in the 18 th and 19th centuries and which was seen as a continuous and neverfinished project, was inevitable and irreversible and which viewed ‘the traditional’ as stagnant, unchanging, almost devoid of history. Modernity and development are therefore very closely intertwined concepts. Bauman: modernity was a world view articulated by and reflecting the world view of educated elites of Europe during the period in which it became commercialized and secularized. They projected their own social, economic and cultural ideals as universal ones towards which all societies should strive. Aimed first ‘against’ traditional ‘peasant’, ‘rural’ of ‘folk’ populations within Europe itself and then against colonial societies which were different. Development, as a discourse centred mainly in the US, carried forward this proselytizing mission after WWII. Unidirectional model of development: societies are divided into traditional and modern, with the goal of social change being to transform traditional into modern societies and cultures. Powerful educational institutions also disseminate the ideal of development to elites from ‘developing’ countries. After WWII, the UN and World Bank defined 2/3 of the world as ‘poor’ and in need of development interventions. ‘Poverty’ also became pathologised, seen against the ‘norm’ of ‘developed’ countries: ‘illiterate,’ ‘underdeveloped,’ ‘malnourished,’ ‘small farmers,’ or ‘landless peasants’. Set up various technologies and knowledge instruments through which ‘development’ would be measured: o Levels of poverty: this was defined through standards of living: those countries and regions in which per capita income was less than US $100 per year were defined as poor. o Yet large regions of the globe only used limited money exchange at this time; they were largely subsistence economies who produced and exchanged goods locally or even traded goods, but not with money. These populations often involved household units that both cultivated and consumed the goods they produced. They were automatically defined as poor. Hunters and gatherers, fishers and other subsistence producers also became, through a stroke of the pen, poverty-stricken. Perhaps then, the goal of ‘development’ discourse was the destruction of subsistence economies and societies and the introduction of market economies so that American and other goods could then be sold throughout the world? The antidote to ‘poverty’ was usually the same prescription: increased commercialization, especially of ‘peasant’ and ‘tribal’ agriculture. But commercialization involved capital-intensive inputs that many could not afford to purchase, e.g. Green Revolution technology. Many lost their lands in the process. Cash crops were substituted for subsistence crops. Rural areas lost the capacity to feed themselves. Capital intensity and cash crop production introduced new inequalities. They were capital and not labour intensive and displaced people from the land. Led to a massive increase in ‘the unemployed’ and a huge low-cost labour force. Subjectification of development discourse: villagers in Nepal began to differentiate themselves in terms of being ‘bikasi’ (developed) or ‘abikasi’ (underdeveloped). “Countries that were self-sufficient in food crops at the end of World War II—many of them even exported food to industrialized nations—became net food importers throughout the development era. Hunger similarly grew as the capacity of countries to produce the food necessary to feed themselves contracted under the pressure to produce cash crops, accept cheap food from the West, and conform to agricultural markets dominated by the multinational merchants of grain” (Escobar 1996).