Document 16059171

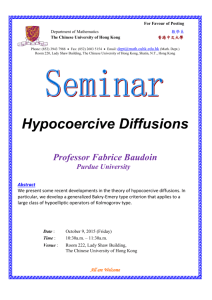

advertisement

LING LING Sheung Hei Wong B.A., California State University, Sacramento, 2008 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ART (Art Studio) at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2010 LING LING A Thesis by Sheung Hei Wong Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Ian Harvey, M.F.A. __________________________________, Second Reader Robert Ortbal, M.F.A. ____________________________ Date ii Student: Sheung Hei Wong I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator Ian Harvey, M.F.A. Department of Art iii ___________________ Date Abstract of LING LING by Sheung Hei Wong In Chinese culture people are not encouraged to express their true feelings through outward appearance. I have discovered how to express inward feelings through Chinese calligraphy. I take ideas from calligraphy where forms and experience are absorbed and recorded through intense observation of nature. I used to be impotent in front of the things that I saw, so in the past I tried not to observe things. Now I rediscover concealed emotions and capture the essence of experience through the observation of objects from my childhood. This allows me to activate fragments of memory and to retrieve what was lost. _______________________, Committee Chair Ian Harvey, M.F.A. _______________________ Date iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………vi LING LING………………………………………………………………………...…… 1 Bibliography…………………..…………………………………………………………23 v LIST OF FIGURES Page 1. Figure 1 Yoshitomo Nara, Hothouse Doll, 1995………,…………....………...14 2. Figure 2 Ling Ling, 2006……………………………………………..…....….14 3. Figure 3 Kar Wai Wong, In the Mood for Love (movie still), 2000.………......15 4. Figure 4 Hong Kong seafood restaurant …...….…………………………...….15 5. Figure 5 Self Portrait with Grandmother, 2008………………………......…..16 6. Figure 6 Grandmother, 2007.……………………………………..……....…..16 7. Figure 7 William de Kooning, Untitled, 1988………...……..…...…………..17 8. Figure 8 Self-portrait, 2008……….……………………………..…..………..17 9. Figure 9 Mountain in Chinese pictograph and character ……..…….….……..18 10. Figure 10 Meng Fu Chao, Picture of three-life man and horse, 13th -14th century ………………………………………………………………...…………...….18 11. Figure 11 His Chih Wong’s calligraphy in curive style.……..….……………19 12. Figure 12 Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1904-06…...….………..……19 13. Figure 13 Ling Ling, 2009……………..…………………..………….………20 14. Figure 14 Unknown graffiti artist ………..……………..………….…………20 15. Figure 15 Ling Ling with Fuzzy Mouse (in Ching Chung Koon), 2009.....……21 16. Figure 16 Dong Song, and Xiangyuan Zhao, Waste Not, 2005...………...……22 17. Figure 17 Ling Ling with Fuzzy Mouse and Puppet, 2009..…………..….……22 vi 1 LING LING Family is always my priority. In my experience, growing up in Chinese culture, I learned to live according to other people’s wills and expectations. I understood that it is necessary to follow the footsteps of recognized “successful ones”. I made decisions without considering personal feelings and desires. I realized that I was not encouraged to express myself until I came to study in the United States. At the beginning, I was terrified to express myself in school because personal expression was never a necessity in Hong Kong. In fact, it has been a privilege for me to learn from both Chinese and American cultures. I have learned that the distinction between Chinese and American culture is based on thinking processes and the way we approach visual information. While developing the ideas in my paintings I draw references from artists, such as MC Yan, Yoshitomo Nara, Kar Wai Wong, Willem de Kooning, Chinese Calligraphers, Paul Cezanne, graffiti artists, Dong Song and Xiangyuan Zhao. When I was a child, I avoided having conversations with myself; however, I allowed myself to have conversations with my doll. Now, I want the freedom to express myself regardless of circumstances around me. I express myself through painting and from observation of childhood toys. I find freedom of expression by capturing the essence of the doll. A deep level of concentration and observation of the doll allows me to reawaken emotions from the past that have been concealed until now. I reduce the distracting elements of Chinese culture, such as excessive interior decoration and individuals’ appearance in order to emphasize visibility of personal expression that is neglected in Chinese culture. 2 MC Yan influenced my thinking process when I was a teenager. MC Yan was a member of the Hong Kong music group, LMF. Their songs gained popularity among the younger generation because of the foul language and the controversial lyrics. Chinese culture does not encourage individuality. Chinese culture supports and praises people when they model themselves after certain "types". In this culture, people only recognize someone who makes money, or the stereotypical idea of a successful person with authority. Every child is influenced by these models and wants to become a successful adult in order to be accepted by society. I am one of the many children who rarely had the opportunity to learn to express myself and learn to be an individual. In the Hong Kong based documentary Dare Ya, MC Yan says, “In Hong Kong, the media is very limited. There are no other channels in Hong Kong beyond the mainstream media… People in Hong Kong don’t raise questions on issues around them. People have not been taught to express themselves.”1 Now, I begin to question things around me. In my experience, growing up in Chinese culture, I did everything according to the will and expectations of someone else. I did not raise questions about events or about the things I did on a regular basis. Although learning to expressing myself is difficult, I realize that I have an eagerness to raise questions that I was not aware of. Yoshitomo Nara’s concepts and his work helped me to understand the sources and motivations that drive my own work (fig. 1). In a KultureFlash interview, Nara says, “I would say that I am interested in the way that the passing of time affects how one remembers particular events… In the same way, how I grew up has an enormous influence on the way that I make art now.”2 When I was a child, I avoided conversations 3 with myself. Nara’s paintings of children reflect my true emotions. He portrays children with unusual expressions that are rarely seen in my culture. His images allow me to look back at myself, and my childhood, with a new awareness. Painting a doll helps me to have a dialogue with myself (fig. 2). Looking at the doll is like having a conversation with my “younger-self”. Nara’s ideas not only help me to understand the motivation that drives my work but also help me to recognize the influences from the constrained society that I lived in. Asian cultures emphasize the need to control outward appearance and behavior. Both Chinese and Japanese cultures are known as highpressure societies. Chinese parents teach their children the importance of controlling their appearance. Nara also draws the comparison between children’s obedience to their parents and a dog’s obedience to its owner. Children learn to obey their parents in order to show respect to their parents. Consequently, the communication between parents and children are insufficient because children suppress their emotion by controlling their appearances. The communication between my family and I was insufficient because of the traditional Chinese parents’ role, especially that of the father as master of the family. My father emphasized the need to learn to control and repress one’s emotions. I felt dejected and needed an avenue for self-expression. Chinese culture promotes people who present an image of “well-being”, “health”, and “happiness”. When I was a child, I was not shy to reveal my true emotions in front of others. Gradually, I learned to restrain my emotions and wondered what were my true emotions. The Hong Kong film, In the Mood for Love, by director Kar Wai Wong, expresses emotions that are bottled up. The environments in the film suggest 4 people and things that are trapped inside interior atmospheres. These atmospheres suggest emotions that are being filtered through dazzling lights and colors (fig. 3). The interior spaces are a main focus in the film. I used to spend most of my time inside buildings. The overwhelming shortage of living space in Hong Kong forces people to live in cramped high-rise buildings. My experiences spending time with family were usually in excessively decorated interior spaces. For example, Hong Kong seafood restaurants are full of stunning decorations and dazzling light, including massive gold sculptures, saturated red curtains and intense spotlights (fig. 4). The structures of these atmospheres confused me and caused me to lose my true emotions. I could not identify my feelings in the midst of these atmospheres. In my paintings, I sort, seek, distill and concentrate visual information that expresses my emotions through excessive visual effect. The figurative elements in my paintings are soaked in the patterning of the interior spaces (fig. 5, 6). In Pop Matters, Jocelyn Szczepaniak-Gillece wrote, “Wong Kar-wai used breathtakingly colored and patterned costumes, ... clashing wallpaper and house decorations… reveal[ing] in the explosive hues that fill both foreground and background…color [which] expresses the delicate twists and turns of love and fate that the characters cannot control ...”3 Wong’s films portray figures that merge with and emerge from the background using the intensity of lighting in the film. In a similar manner, I use a full range of color in my paintings, both in the foreground and background, to create a sense of longing and timelessness. I am questioning the obsessive awareness of the perfection of outward appearances, such as an individual's appearance and home decoration, which hide one’s true emotions. Although my 5 culture’s custom of suppressing one’s ideas and emotions makes me uncomfortable, I discover my true emotions by setting up still life environments in which I recreate an atmosphere similar to those I experienced in the past. I have been encouraged to express myself by painting family and self-portraits. However, I am still struggling to work toward a freedom of expression through painting. In Willem de Kooning’s late paintings, his colors, lines and forms suggest freedom of expression. In Willem de Kooning: The Late Paintings, The 1980s, Gary Garrels wrote “The simplification of form, the uninterrupted flow and contour of line, the large area of color, sometimes subtly bled and modulated, are recalled directly in the paintings of the late period.”4 The lines and forms in de Kooning’s paintings are simplified, and yet the convolution of lines and forms suggests complexity of emotions (fig. 7). While painting from observation, I distill the colors, lines and form from the complexity of my still life with a doll. The ribbon-like movements of color in my paintings merge on the canvas and suggest the human form of the doll (fig. 8), and the uninterrupted movement of lines and forms suggest the fluidity and freedom of the emotions. Past and contemporary Chinese calligraphy artists maintain a tradition that cannot help but influence my own form and content by the fluid movement of calligraphic strokes. Chinese calligraphy has persevered as an art form since the beginnings of ancient China. The earliest Chinese pictographs are considered to have been introduced into the Chinese way of life in the Shang dynasty, between 1800 – 1100 B.C. Chinese pictographs suggest forms according to their appearance in nature. 6 For example, the pictographic symbol for a mountain is based on the simplified form of mountains found in nature (fig. 9). The Chinese written language has evolved through subjective experience and observation. For instance, the Chinese character for moon is 月. The Chinese ancient form of moon is very similar to the modern. The form suggests a new moon based on natural phenomenon and uses the shape of a new moon rather than a full moon. Chinese characters not only convey the meaning of the word but also express, or mimic, their visual counterpart in nature. Chinese painting and calligraphy draws first from the visual information. In The Chinese Eye, Yee Chiang uses a quote from Chinese painter and calligrapher Chao Meng Fu from the 13th or 14th century. He describes painting and calligraphy as being the same and having no distinction.5 (fig. 10) Chinese calligraphy and painting are based on direct experience and observation of nature. In CCTV’s show – We, contemporary painter and calligrapher, Zeng Fan explains by saying that, “Painting has to attain pleasure and impulse from calligraphy. Also, calligraphy has to attain meaning and implication from painting. This is how one accomplishes the state of enjoying something without restraint… They (calligraphy and painting) connect to each other… Painting and calligraphy are basically the same thing.”6 I applied the stylistic elements of calligraphy, and I realized that Chinese painting and calligraphy are closely related to one another. I find that the connection between calligraphy and painting is based on intimate experience and observation of nature. Chiang continues to describe how Chinese calligraphy and paintings “extract the essentials from appearance”5. Those coming to my work from a Western perspective are most likely to approach them in terms of abstraction. The same reduction or 7 simplification of line and form that can be found in western abstract painting is found in Chinese landscape painting and my own paintings of the doll. However, my Chinese traditions of painting do not make a distinction between representation and abstraction. I simply strive to capture the essence of form through observation. Chiang also mentions, “In figure-painting and in poems descriptive of human life we do not aim at verisimilitude, but at extracting both formal and the imaginative essence.”5 In my painting process, I record the visual information from intense observation. I see the vitality of the figure of the doll in an interior atmosphere. Although the doll and the space that I have created for it are not real, I find the doll and its environment still have a life in themselves. His Chi Wong’s cursive style of the character – 逐 (Sui) literally means “to follow” and suggests the mobility of a female figure. (fig. 11) Wong’s calligraphy corresponds to the meaning of the Chinese character and stresses the movement rather than the figure itself. Chiang uses the illustration of the dancing figure in ancient China to compare with the character that represented them. I use the doll as a reference when I imply vitality to the doll. Indeed, I am not trying to capture the factual appearance of nature, rather, I hope to record visual information based on impulses and perceptions achieved by intense concentration. Through deep concentration, I can see and imagine the vivid life of the doll beyond its actual appearance. While painting I seek to record this life. In this respect, the practice of Chinese calligraphy, and its methods of interpreting the visual aspects of life and nature, is essential to my paintings. 8 Paul Cezanne’s paintings reveal the intensity of the visual information he received from a deep and penetrating observation of nature. The series of paintings titled, Mont Sainte-Victoire, show different levels of concentration in his observation of nature at different periods of time. (fig. 12). My paintings expose emotions through different levels of concentration. I absorb forms and colors from appearances. Each brushstroke suggests the mobility of the human figure. The abstraction of the figurative elements in my paintings is the result of my concentration and the process of recording the visual information of my vision. In Theory of Modern Art, Cezanne is quoted as saying, “We must render the images of what we see, forgetting everything that existed before us… Now being old, nearly 70 years, the sensation of color, which gives light, is the reason for the abstraction.”7 Although he mentions that his vision has changed with age, he writes that his vision of nature has become clearer and that this clarity was the reason of the abstraction in his works. Cezanne draws reference from natural lighting and the natural world, but the penetration of Cezanne’s vision suggests a dream-like atmosphere. My painting implies memories of a dream-like landscape. Although my painting has landscape elements, these elements suggest both internal and external atmospheric qualities. (fig. 13) The light quality suggests a space that is both interior and exterior. As I have been informed by viewers, the forms in my painting draw reference from fire. Fire is translucent, and its light suggests an urgency and intensity of emotion. The continuous motion of the burning fire suggests a world in which things and events are in continuous motion. The transparency of the paint suggests things or events that are not recent. The interweaving of things and events allows emotions to 9 show up and be visually recognizable in the painting. The paint conveys different kinds of substances, such as natural phenomena, atmospheric qualities and emotional experiences. As I have mentioned, I want to express intense emotion and freedom of expression in my paintings. I want to enhance the visibility of these elements. The way in which lines and forms move through and against each other suggest battle, conflict or struggle within the internal world. In the high-pressure society of Hong Kong, there are no alternatives. The main stream focuses on material life and economic development. I am in conflict with my family. My family, like many others in my culture, experienced extreme poverty in the past. Many of them consider economic development to be the priority and necessity in society. My goal was to be a good student and to be accepted by a university. I learned to strive for this goal in order to have a better life in the future. My father always says that “quality of life” and “a happy life” are extra in relation to the “foundation of life”. For him, material life and money provide the quality and “foundation of life.” I am not sure how to attain a “quality life”, but I have lost my true identity under the influence of my culture. I have failed to fulfill my family’s social expectations. It is hard to accept the older generation’s thoughts and values. I seek different alternatives, such as personal values and expression that my culture considers to be unimportant. The mechanical development of individuals based on strict social expectations results in a lack of appreciation for creativity. Hong Kong is a one of the biggest art markets in the world, larger than New York and London, but Hong Kong never focuses on cultural development. Graffiti 10 artists are seeking attention in order to have a voice as individuals and to be recognized by the general public. (fig. 14) In Graffiti NYC, quoting a resident of New York City, Dr. Patricia Hill says, “It’s all about having an identity and simply being recognized and acknowledged, which we all need. If people cannot get that kind of validation through socially acceptable means, they will find other ways to fulfill their needs.”8 Graffiti is a means by which the artist’s existence can be recognized, and the general public can be forced to pay attention to their situation. Therefore, huge scale and wall size images are necessary. I desire to explore expression that I cannot explore in a life based on materialistic goals. I am not satisfied with the idea of fitting my development into a mechanical mold. As an individual I want to be acknowledged and recognized by the society (fig. 15). I feel that I represent a way of life that is neglected, or rejected, by most people in my culture. My experience in both primary and secondary school had a great impact on me because I was not treated as an individual. I believed I was “useless” or “rubbish” based on my poor performance in school. I had no choice but to accept myself as unworthy in society. I tried many ways to change myself and to be better in the eyes of my culture, but I could only be myself. As I was occupied with worries for my future, I did not develop my desire to express myself. Now, based on my exploration in painting, I understand more clearly the importance of personal expression. Although I do not need everyone to understand completely the meaning of my works, at the very least I want them to pay attention and maybe understand the importance of personal expression. 11 The conflict between my family and I is based on the barrier between my family’s history and my personal experience. I had an intimate relationship with my grandmother. She is the person for whom I have the most respect. Indeed, she was a person who always encouraged me regardless of the circumstances. The hardship she went through in the past, especially during the Chinese Cultural Revolution, was tremendous. She escaped with her children from Mainland China to Hong Kong regardless of the heavy price she paid to insure their future. The fear of material shortages was always a concern for my grandmother. Although her quality of life improved in Hong Kong, she still continued her habit of collecting discarded objects. As a child I did not understand the reason behind her habit, but I supported her idea that things can be used again and again. My father was always annoyed with the discarded objects she collected and packed in the small bedroom that I shared with her. I always argued with my father about the discarded objects she collected. One day, she brought me to a remote area in Hong Kong near the border of Mainland China. She told me that it was the home where she first stayed when she escaped from Mainland China. She looked for things and she gave me a doll that she had stored there. For me, as a child growing up in a middle class family in Hong Kong, the old doll seemed out of place. However, this doll is my favorite compared to all the others I had because it carried the strongest memories of a lavish life in Hong Kong. Although the doll is very old and in bad condition, I see traces of my family in it. In a collaboration piece titled, Waste Not by artist Dong Song and his mother Xiangyuan Zhao , an incredible amount of discarded objects are displayed in an installation piece. (fig. 16) Because the 12 relationship between discarded objects and family history are essential for me to understand my work, I use discarded objects as a reference. In Waste Not: Zhao Xiangyuan and Song Dong, art historian Hung Wu wrote, “For Chinese frugality is a traditional virtue, but at that time it was also the only way for a family to survive.”9 I began to understand my grandmother’s history based on our conversations about these discarded objects. These objects were an important vehicle for our communication. Wu continues to say, “The installation has gradually transcended its familial origin to become a vehicle of human communication. Whereas the project has strengthened the connection between the objects and their original owner and her family.”9 The discarded objects enhanced the relationship between my grandmother and me. I gradually realized the reason why my grandmother collected the objects throughout her life. She hoped her future generations would be able to live a better life, and would not have to undergo the hardship she went through in the past. Zhao wrote, “When Dong Dong (refers to his son Dong Song) got married, he and his wife decided they would be ‘DINKs’ (double income, no kids), but we parents had no idea about that, so I always believed that after a while they would have a baby. So whenever Momo (Zhao’s daughter’s child) wanted to throw toys away… I would collect them, keeping them for the ‘baby’.” 9 In the same way, my grandmother believed all the objects she saved could benefit future generations. I knew the reason my grandmother saved children’s toys throughout her life was her love for the future generations. Her habit of collecting discarded objects gave me an emotional attachment toward the objects she collected (fig. 17). I began to think of these discarded objects as having a life of their own. 13 Therefore, specific objects, like a doll and a toy fur mouse that my grandmother gave to me, inspire the ideas in my paintings. The doll that my grandmother gave me is no longer with me, but I searched for a doll and found one that reminds me of the connection with the doll that I had in the past. These toys carry traces of my family life, including my grandmother’s life. I always have had a strong desire to express myself, especially toward my family. However, I have not accepted and confronted my true emotions even toward important people in my life. After my grandmother passed away, I had an eager urge to express myself. The toys have now become a vehicle for self-expression. I used to be impotent in front of the things that I saw, so I tried not to observe things, especially on the level of understanding my emotion as well as others. Now I have begun to be aware and to penetrate to deeper, suppressed emotions painting these toys from observation. Diverse artists from different time periods help me to see and understand my work. I will continue to investigate painting in order to serve my emotional content and expression. Space, memory, time and light are always significant in order to create rich visual information to serve this expression. My investigation will be based on observation of natural phenomenon and the natural environment. I will explore different kinds of paint application to suggest different atmospheric qualities. The experience of painting from nature is one of surprise and abundance. I hope to explore the synesthetic possibilities of paint in relation to the experience of natural phenomena. I believe all the senses can be conveyed in painting and they are part of the essence of natural experience. 14 Figure 1 Yoshitomo Nara, Hothouse Doll, 1995 Figure 2 Ling Ling, 2006 15 Figure 3 Kar Wai Wong, In the Mood for Love (movie still), 2000 Figure 4 Hong Kong seafood restaurant 16 Figure 5 Self Portrait with Grandmother, 2008 Figure 6 Grandmother, 2007 17 Figure 7 William de Kooning, Untitled, 1988 Figure 8 Self-portrait, 2008 18 Figure 9 Mountain in Chinese pictograph and character Figure 10 Meng Fu Chao, Picture of three-life man and horse, 13th -14th century 19 Figure 11 His Chih Wong’s calligraphy in curive style Figure 12 Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1904-06 \ 20 Figure 13 Ling Ling, 2009 Figure 14 Unknown graffiti artist 21 Figure 15 Ling Ling with Fuzzy Mouse (in Ching Chung Koon), 2009 22 Figure 16 Dong Song, and Xiangyuan Zhao, Waste Not, 2005 Figure 17 Ling Ling with Fuzzy Mouse and Puppet, 2009 23 BIBILOGRAPHY 1. "Dare Ya!: LMFamily." DVD, Directed by Louis Tan. Hong Kong: Asia Video. 2003. 2. James Lindon. Interview with YoshitomoNara. "Artworker of the week #58: Yoshitomo Nara." Kultureflash. February 2, 2006, http://www.kultureflash.net/archive/154/priview.html (accessed June 5, 2009) 3. Jocelyn Szczepaniak-Gillece. "Living in Dreams: Wong Kar Wai." Pop Matters, June 3, 2004, http://www.popmatters.com/film/features/040603-karwai.shtml (accessed August 2, 2009) 4. Gary Garrels, and Elise S Haas. Willem De Kooning: The Late Paintings, The 1980s. (Minneapolis: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Walker Center. 1995) . 5. Yee Chiang. The Chinese Eye: An Interpretation of Chinese Painting. 2nd ed. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1964) . 6. Zeng Fan. “We: Fan Zeng Talk about Beauty of Chinese Calligraphy.” CCTV. February 15, 2009, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oNZlLoSjk44 (accessed Feburary 12, 2010) 7. Herschel B Chipp. Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics. (Los Angels: University of California Press, 1969) . 8. Hugo Martinez. Graffiti NYC. (London: Prestel, 2006) . 9. Hung Wu. Waste Not: Zhao Xiangyuan and Song Dong. (Tokyo Gallery and Beijing Tokyo Art Project, 2006) .