STORYTELLING A Thesis Presented to the faculty of the Department of Art

advertisement

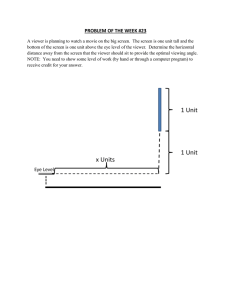

STORYTELLING A Thesis Presented to the faculty of the Department of Art California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Art Studio by Bradley Starkey-Owens SPRING 2014 STORYTELLING A Thesis by Bradley Starkey-Owens Approved by: __________________________________, Graduate Coordinator Andrew Connelly, M.F.A. __________________________________, Graduate Advisor Rachel Clarke, M.F.A. ____________________________ Date 2 Student: Bradley Starkey-Owens I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator Andrew Connelly, M.F.A. Department of Art 3 ___________________ Date Abstract of STORYTELLING by Bradley Starkey-Owens I wanted to become as aware of myself as possible. I wanted to understand my actions and motivations within the context of my every day life, from my distinct perspective. I have explored the process of telling my stories through video and other forms of digital media. I have viewed and researched the foundations of character, setting, form, and narrative to become the most effective storyteller I can be. _______________________, Graduate Coordinator Andrew Connelly, M.F.A. _______________________ Date 4 DEDICATION For my wife, my parents, and my siblings; whose unending support and understanding make everything possible. 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Dedication ..................................................................................................................... v List of Figures ............................................................................................................ vii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION/CONTENT………………………………………………….. 1 2. CHARACTER ........................................................................................................ 5 3. SETTING ................................................................................................................ 8 4. FORM ................................................................................................................... 11 5. NARRATIVE ....................................................................................................... 15 6. CONCLUSION ..................................................................................................... 18 Works Cited ................................................................................................................ 19 6 LIST OF FIGURES Figures Page 1. Bruce Nauman, Still from Mapping the Studio I , Video, 2001 ………………… 4 2. Brad Starkey-Owens, Still from Untitled Video, 2014 …………………………. 4 3. Brad Starkey-Owens, Still from Persistence, Video, 2013 .…………………….. 6 4. William Wegman, Still from Massage Chair, Video, 1972-73………………….. 7 5. Bill Brown, Still from Chicago Corner, Video, 2009.…….……………………. 9 6. Brad Starkey-Owens, Still from Achieve Zen, Video, 2013..………….………. 12 7. Wes Anderson, Still from Moonrise Kingdom, Film, 2012 ..…………………. 13 8. Wes Anderson, Still from The Darjeeling Limited, Film, 2007……….……….. 13 9. Wes Anderson, Still from The Fantastic Mr. Fox, Film, 2009…………..…….. 13 10. 11. Brad Starkey-Owens, Still from Relative Filth, Video, 2013.…………………. 14 Dan Harmon’s Story Circle……………………………..……………………… 16 12. Brad Starkey-Owens, Still from Change, Video, 2013………………………… 17 7 1 INTRODUCTION/CONTENT: My work is reflective. I am interested in the subtext of daily life; the moments between the moments by which I navigate my past, present, and future. Experiences that are considered to be “life changing” are few and far between. Much more of my actual life is taken up by commuting, making sandwiches, cleaning, and sleeping. It feels disingenuous to address the exciting without the mundane. I know how I feel when I start a new job or go on a vacation, in a life changing moment, so it is important that I explore and share the mundane experiences that will likely be otherwise forgotten. I work in an effort to keep from losing them, by magnifying and slowing them down so that they become as visually and experientially inspiring as their traditionally more memorable counterparts. This approach has developed over the course of my time as a graduate student. Working initially in still images in Photoshop and Vector, I did not find my voice until my second year of the graduate program. As an Undergraduate student I used a sociopolitical rhetoric. I was interested in making a lot of noise and sharing my radical opinions concerning religious inequality. As an atheist, I thought that I had experienced 2 repression. I saw Christian symbols and values in public places and felt as though I had no representation of my own. It became my mission to begin a conversation, by pointing out my perceived repression and calling peers to arms. At the time it was my belief that the role of the artist is to make change; to speak directly to social issues and convince viewers to take action. Using bright, abrasive colors, I aimed to grab the viewer’s attention and hold them long enough to question the constructs of the world and society in which they exist. I was didactic, aggressive, and passionate; but tragically uninformed. Though I do still believe that seeking real social change is a noble conviction, I now recognize that my own goals were naive and idealistic. This type of work requires passion, patience, and education that only in hindsight do I realize that I lack. Working in such a way proved to be consistently untrue to my nature, and grossly irresponsible. In my growth as an artist and as a person I have learned that I do not have a naturally aggressive personality, and should not feel obligated to generate temporary emotion for the sake of activism. Instead I find a more quiet, nuanced approach is in line with my natural mode of being. I am candid, sharing moments of my life that would likely go unseen by those outside of my household. I expose my habits, concerns, and pettiness. I share the smallest moments that generally carry very little weight on their own, and transform them into dramatic, momentous occasions. Light and sound are stretched and magnified. The viewer is given a window into the emotions and motivations of the subject, as elongated time highlights details in expression and body language that is lost in real time. Stretched sound led to exaggerated bass, creating an 3 environment that feels familiar, but outside of reality. Viewers connect emotionally with familiar activities, while being held by the drama of cinema. The routine events that make up the majority of life are slowed down to reveal their importance. They make up who we are and expose more of our character than anything we could express intentionally. In this way, my work has also become a series of self portraits. Each of them exposes some small tendency or characteristic that I am often not even aware of until I view it myself. For this reason, it is a necessity that I be completely honest with myself and my viewer. When I am physically present in the work, it is only a performance in the most literal sense: an intentional action that is recorded to video. In practice, performances just feel like living. Each action is one that I would execute in my life. Each facial expression is a true reaction to my environment, or an interpretation of what is happening in my head. The moment that I begin acting for the camera, I have to stop the performance and put the piece aside. The video work of Bruce Nauman is just the first of a number of video artists that have had a direct effect on my work. As an undergraduate student, I knew only of Nauman because he is a graduate of UC Davis. As I became more familiar with his work and my own, I have grown a great admiration for his approach. His 2001 piece Mapping the Studio I (Fat Chance John Cage)1 completely changed the way I think about making. The piece runs 345 minutes long, showing nighttime surveillance footage of Nauman’s studio. There are no events or overt story lines that take place. The only real 4 content is in the absence of happening. This has been a recurring theme throughout Nauman’s career. In 1979 he said: “What is it that an artist does when he is left alone in his studio? My conclusion was that if I was an artist and I was in the studio, then everything I was doing in the studio should be art…From that point on, art became more of an activity and less of a product.” This sentiment resonates with me and applies to my work. My subject matter is that of daily life; average experiences. It is honest, reflecting on the actions that I take on a regular basis. I do not attempt to embellish or perfect my actions. Like Nauman, I explore my role of artist as an imperfect, boring human. Anything I do has the potential to become art, provided it is the correct context. Figure 1: Bruce Nauman. Mapping the Studio I (Fat Chance John Cage), 2001. Video still. Figure 2: Brad Starkey-Owens. Untitled Video still. 2014. 5 CHARACTER The development and employment of accessible, believable characters is an integral aspect of my work. This is why it is essential that I remain honest in the sentiment and execution each piece. Using myself, my pets, and my (unbelievably patient) immediate family members as subjects, I am able to capture organic moments and routine events as they arise. The most difficult aspect becomes finding the correct way to capture such moments, so that they are portrayed both as honestly as they happen, and with enough information to deliver the intended sequence and mood to the viewer. I have found a distinct difference in the recurring characters that appear in most pieces, and the protagonist that arises in each individual moment. Because the development of these subjects has been so honest and organic, they often evade the “hero” status that is generally expected of a main character. Instead, the role remains absent, or is assumed by the environment or objects that the subject is in conversation with. In Persistence, my character attempts to make a lawnmower start. He goes through the motions of checking the oil, adding gasoline, and pulling the start cord. As the video advances, he remains unsuccessful, and the viewer becomes frustrated with his lack of 6 real effort. In a traditional narrative, the main character would be confronted with a problem, fail initially, learn something new or grow in some way, then find success in his or her new found qualities. In Persistence, the character never grows or becomes successful. He gives a half-hearted Figure 3: Still from Persistence. 2013. effort before giving up. This is where the antihero character is created. The viewer relates to him or her because the situation is familiar, but comes away frustrated because they are left without the heroic or competent characteristics expected of a traditional protagonist. I have learned a lot about unconventional character development by viewing the work of William Wegman. In his video work from the 1970s, he creates a universe in which the logic we understand does not exist. He pokes fun at modern norms by intentionally misusing common items. In Massage Chair, he presents a perfectly normal chair, that one might find in an office or classroom, as a brand new line of massage chair. He points out its new features and demonstrates its use by sitting in it and beating the side of it with a stick. He makes no effort to frame this as reality, clearly sitting in his studio dressed in plain clothes, and delivers the lines in a very deadpan manner. The viewer does not find similarities to connect to the character. Instead, Wegman invites comparison in search of differences. The viewer can find quite quickly what is wrong 7 with the character, presenting something so ordinary as an exciting luxury item, and is able to quickly realize the commentary that the artist is making. This brand of antihero development has served as invaluable research in my own work. Though I invite closer comparison to the viewer’s actual experiences and request more patience, the underlying idea is quite similar. Figure 4: William Wegman. Still from Massage Chair. 1972-73. 8 SETTING By my definition, the setting of my work includes the physical location, the placement in time, and the mood of each piece. These aspects are the first and most direct information that I give to the viewer. They work together to form a view from my perspective, and create a solid foundation to build characters and narrative upon; thereby grounding the content in a familiar, comprehensible universe that allows the viewer to grapple with some of the more nuanced ideas addressed by the individual piece. The location of my work is generally very familiar to me. If a piece does not take place in my own home, it is generally a place that I frequent, or have frequented in the past. Working with personally important locations allows me to work from a place of genuine experience. Unlike previous work, nothing is manufactured. Each experience portrayed is one that I have had before, manipulated and dramatized for a screen. Working so closely with such relevant items and places in my life allows me to become much more connected to the work. I am invested in a way I could not be if my set were scouted or manufactured for the sake of agreeable lighting or filming space. This 9 suburban home and landscape, which is extremely ordinary by most measures, speaks to me in a way that no other setting could. Engaging my own surroundings so intimately has brought me closer to them. As a young ambitious student from Vacaville, I grew up with a mentality that the most important first step in my success is leaving my hometown. I would romanticize any other location I visited, assuming anywhere must be more interesting than what I was used to. A huge step in my development as an artist and an adult has been learning to accept that Vacaville and Northern California are an integral part of my perspective and identity. I have been heavily impacted by the work of Bill Brown. A nomadic filmmaker, Brown describes his work as a series of “Postcards.” He uses location not just as setting, but as subject; creating a somber mood and addressing the struggles of a given area. In Chicago Corner specifically, Brown examines a dilapidated area of Chicago, Illinois. He shares personal stories of the area’s citizens, asking important sociopolitical questions with his framing of the working poor. The viewer is provided no image of the interviewed individuals, only the sound of their voice. With only images of the city, the viewer is left Figure 5: Bill Brown. Still from Chicago Corner. 2009. 10 to reconcile the struggle and character attributes of the individual vs. the community, and the city as a whole. Aside from the sociopolitical themes, my work is similar to Brown’s in that the location is often just as important as any character or plot point. The familiarity of a dirty stove, an overgrown yard, or an average living room allows the viewer to connect in the same way they would to a Chicago city corner. By setting a stage and controlling a specific but seemingly familiar scene, a foundation is created for a shared common experience. While supplying a protagonist and a narrative, the work functions as a mirror for the petty transgressions and concerns of day-to-day life in the first world. It looks closely at common frustrations with domestic life, posing a question about the value of our collective struggle as a people. 11 FORM Video is a medium that I am constantly relearning. I have been making short videos since I was fourteen years old, but the available technology advances so rapidly that I must change my process every six months or so. The need for growth and change is what has kept me interested in the medium for so long, and the use of something so new to portray such simple ideas remains exciting. Many of the aesthetic choices I make have developed over time. First by learning the basic rules of filming and framing, then by breaking each of those rules, then by finding my own aesthetic interests and applying what I have learned. I have a natural tendency to find brightly colored objects and place them into dull settings. In Achieve Zen, I use a tangerine and a tea packet at opposite ends of the frame to direct the viewer’s attention across the screen. The gray and brown middle ground provide important support for the high key items, completing the composition and leaving the viewer unprepared for the perspective shift that takes place. 12 Figure 6: Still from Achieve Zen. Digital Video. 2013. The films of Wes Anderson are characterized by nearly-symmetrical frames dominated by a single color, often yellow. For those who know his work, it is impossible to mistake. His use of color has been an immeasurable influence on my work. It has greatly informed the attention I pay to form. Anderson will generally use an extremely shallow depth of field and a color wash across an entire frame. I have recognized by viewing his work that my own preferences are almost exactly the opposite. Where his color is relatively dull, and spread throughout, mine is much higher key and only in concentrated areas. One aspect of his work that I do find myself attempting to emulate is his use of space. He manages to get as many characters into a single frame as possible without making it feel cramped. It was his work I had in mind while meticulously framing each shot of the work in my Advancement to Candidacy Exhibition. In Relative Filth, each item is placed very particularly. The camera is level on a table, on which debris can clearly be seen. A tupperware container and a jar of barbecue sauce show reflections of an otherwise unseen character as he moves around the room. As the video advances, a bag of raw chicken is dropped in front of the camera, taking up much of the 13 screen. The placement of the bag is such that the viewer sees juices drip and run down the inside of the bag for a brief moment, before the bag is removed from the frame. The sound of a refrigerator opening and closing provides tracking of the character when his reflection disappears; every element is orchestrated to ensure that the viewer has a full Figure 7: Still from Moonrise Kingdom, 2012. Figure 8: Still from The Darjeeling Limited, 2007. Figure 9: Still from The Fantastic Mr. Fox, 2009. Wes Anderson. 14 understanding of the sequence of events, without ever showing the protagonist, or an establishing shot of the kitchen. Figure 10: Still from Relative Filth. Digital Video. 2013. 15 NARRATIVE I constantly research storytelling techniques from many forms of media. Conventional storytelling dictates that an effective narrative includes a beginning, middle, and end. There is a protagonist, and antagonist, a conflict, a climax, and a resolution. This is historically the most effective way to introduce an audience to a setting, get them invested in a universe, and satisfy them with appropriate closure. Though there are variations on this, the basics remain the same. Dan Harmon, creator of the television series Community on NBC, has refined his storytelling process to an even more finely defined science. He has developed a “Story Circle” that defines eight points that his characters must hit over the course of each episode, over the course of a season, and over the course of the entire series. The eight points are: 16 1. A character is in a zone of comfort, 2. But they want something. 3. They enter an unfamiliar situation, 4. Adapt to it, 5. Get what they wanted, 6. Pay a heavy price for it, 7. Then return to their familiar situation, Figure 11: Dan Harmon’s Story Circle. 8. Having changed. I find this approach to be very satisfying. Watching any episode of television, or any film, I am able to find these points throughout the story with very little variation. It is extremely important that I be familiar with these guidelines so that I may be effective in my own attempts to tell story in a less conventional manner. A common quote from Dalai Lama XIV has become a bit of a cliche, but proves to be valuable: “Know the rules well, so you can break them effectively.” One way that I deviate from conventional narrative is by withholding the resolution. When done effectively, this tactic echoes my point that the conclusion, or the “big event” is not always the most important puzzle piece, though it is the most satisfying. Not buttoning everything up with a clean resolution requests some effort on the part of the viewer. In Change, a piece from my Advancement Exhibition in October 2013, the viewer drops in on the character as he prepares for the day. Though he remains largely unseen, it is clear that he is changing his clothes. A very uncomfortable tension 17 builds as the viewer drops in on this intimate moment. A zipper is heard, a pair of shoes is moved, and the video ends. There is no resolution; no punchline to this awkward intrusion. The lack of satisfaction leaves the viewer to Figure 12: Still from Change. 2013. consider only what is presented: the content of the moment. Visual and audial details of the room become much more important when a viewer does not feel that everything has been resolved. I continue to learn from a plethora of resources. This American Life, a radio series on National Public Radio and television series on Showtime, has informed my approach to voice for a number of years. The show has a quiet sensibility, and each writer has a way of arranging words to relay a story, focusing on people. In many cases, very little actually happens in an anecdote. By placing the emphasis on the person, the story becomes about the experience rather than the event. This has played a large role in my interest in toeing a line between documentary and scripted narrative. It has also been my introduction to the idea that the events of daily life can be just as important as larger, more overtly exciting events. 18 CONCLUSION Above all, I aim to establish common ground with my viewer. We share a familiar event in an unfamiliar way. We see our struggles, transgressions, and frustration in a way that allows us to re-experience them and examine our motivations. We see how we affect the people around us and the environment we inhabit. We gain awareness of ourselves and empathy for others when we understand that our individual universe is not selfcontained. It is an intersection of countless experiences by countless individuals who all have concerns, frustrations, and motivations of their own. While I hope to reach others with my work, the largest impact is always made on myself. The experience of making is immeasurably cathartic. My work affects me as much as I affect it, delving into crevices of ego and self-deprecation. It finds tangled knots of experience and memory and sorts through it, so that I can see where they begin and end while examining every kink and twist along their length. It actively affects the way that I see myself and the people around me. It is an unending source of advice that can only result in growth as an artist and as a person sharing the world with everyone around me. 19 WORKS CITED 1. Segment: Bruce Nauman in “Identity,” Art 21, Accessed April 5, 2014, http://www.pbs.org/art21/artists/nauman 2. Dan Harmon, “Story Structure 101”. Channel 101. Accessed April 6, 2014, http://channel101.wikia.com/wiki/Story_Structure_101:_Super_Basic_Shit