ASSESSMENT OF ENGLISH LEARNERS : GUIDELINES FOR BEST PRACTICES

advertisement

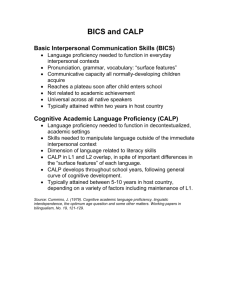

ASSESSMENT OF ENGLISH LEARNERS: GUIDELINES FOR BEST PRACTICES Natalia Borisov & Megan Landreth Purpose of This Workshop This information is designed to guide school psychologists and special education program specialists practicing in the field today when assessing EL students in an effort to better serve this growing, at-risk population of students. Presentation Outline 1. Why Focus on EL Students? 2. Legal History of Assessment 3. Current Regulations 4. EL Learning Trajectory 5. Importance of Native Language 6. Overrepresentation in Special Education: SLD & ID 7. Current Assessment Methods 8. Best Practice Methods & Tools 9. Case Studies 1 & 2 10. Q&A Why Focus on EL Students? Growing numbers of ELs in U.S. schools From 1997-98 to the 2008-09 school years, the number of EL students increased from 3.5 million to 5.3 million, a 51 percent increase Uneven literacy performance of EL 4th graders reaching basic reading competency compared to 70% for non-EL 29% of EL 8th graders compared to 77% of non-EL 30% Why Focus on EL Students? cont. The dropout rate for EL students is 15 to 20 percent higher than for the general student population EL students are overrepresented in special education programs EL students have lower academic achievement as compared to non-EL students There is a lack of research, best practice guidelines, or “definitive“ protocol for this population Legal History for Assessing Minority & Disabled Individuals Civil Rights Act of 1964 U.S. Department of Health, Education, & Welfare Memorandum, May 1970 School take districts must: steps to rectify the language deficiency in order to open the instructional program to the students Avoid labeling students as mentally retarded based on criteria that reflected their limited English proficiency Ensure that “ability grouping” or tracking system used by the school is not a “dead-end” Notify minority parents of school activities in the appropriate language Legal History for Assessing Minority & Disabled Individuals, cont. Education for All Handicapped Children, 1975 Ensured that all students with disabilities would receive school services Lawsuits Legal History for Assessing Minority & Disabled Individuals, cont. Diana vs. State Board of Education, 1970 Children could not be identified as mentally retarded based on culturally biased tests given in a language other than the child’s native language. Larry P. vs. Riles, 1979 Court ruled that IQ tests that have been normed on all-white population could not be used for special education eligibility for minority students. IDEA, 1989 The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act This law applies to state agencies that accept federal funding Requires these agencies to provide early intervention, special education, and related services to children with disabilities. IDEA 1997 & 2004 Amendments Limited English proficient students cannot be found eligible for service if the primary reason for their learning problems are the result of environment, cultural, or economic disadvantage. IDEA Assessment Guidelines Evaluation and placement procedures must be conducted in the child’s native language, unless it is clearly not feasible to do so. Assessment results must be considered by individuals who are knowledgeable about the child, assessment, and placement alternatives . Parents must understand the proceeding of IEP meetings and also have the right to an interpreter at the cost of the district; and The multidisciplinary team must consider the language needs of students when developing, reviewing, or revising IEPs. Why So Vague, IDEA? Guidelines are left intentionally vague to allow more freedom in assessment practices. However, that frequently results in confusion and biased testing. Federal and California Code of Regulations to Protect ELs FCR: “A child may not be determined to be eligible… if the determinant factor for that eligibility determination is… lack of instruction in reading or math, limited English proficiency… and the child does not otherwise meet the eligibility criteria under 300.7” CCR: “The normal process of second language acquisition, as well as manifestation of dialect and sociolinguistic variance shall not be diagnosed as a handicapping condition.” NASP’s Ethical & Legal Standards NASP Guidelines School psychologists pursue awareness and knowledge of how diversity factors may influence child development, behavior, and school learning. In conducting psychological, educational, or behavioral evaluations or in providing interventions, therapy, counseling, or consultation services, the school psychologist takes into account individual characteristics… Practitioners are obligated to pursue knowledge and understanding of the diverse cultural, linguistic, and experiential backgrounds of students, families,… School psychologists conduct valid and fair assessments. They actively pursue knowledge of the student’s disabilities and developmental, cultural, linguistic, and experiential background,… So are we ready to work with ELs? Many special education team members feel underprepared for working with EL students (Mueller, Singer, Carranza, 2006) The results of a survey of current practices with ELs indicate that school psychologists select, administer and interpret tests for minority students in the same way as they do with monolingual students (Ochoa, Riccio, Jimenez, Garcia de Alba, & Sines, 2004) Learning Trajectory for EL Students Expected Trajectory: BICS vs. CALP Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS) Typically acquired in 1-2 years Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) Typically acquired in 2-7 years Source: Collier, V. P. (1989). How long? A synthesis of research on academic achievement in a second language. TESOL Quarterly, 21(4), 617-624. L2 Acquisition Stages • Silent Period • Focusing on Comprehension Stage 1: Preproduction (first 3 months) Stage 2: Early Production (3-6 months) Stage 4: Intermediate Fluency (2-3 years) Stage 3: Speech Emergence (6 months – 2 years) • Improved comprehension • Adequate face-to-face conversational proficiency • More extensive vocabulary • Few grammatical errors Source: Rhodes, R.L., Ochoa, S.H.S, Ortiz, O. (2005). • Focusing on comprehension • Using 1-3 word phrases • May be using routine/formulas (e.g., “gimme five”) • • • • Increased comprehension Using simple sentences Expanded vocabulary Continued grammatical errors Possible Factors Contributing to Delayed L2 Acquisition Mostly, it’s due to: But sometimes, it’s due to: Cultural Factors Deficits in Phonological Skills Delayed Second Language Acquisition Family Factors Personal and Intrinsic Factors Environmental Factors L1 Schooling Quality and Quantity Factors Contributing to Delayed L2 Acquisition Poor self-concept Withdrawn Personality Anxiety Lack of Motivation Traumatic Life Experience Difficult Family Situation Different Cultural Expectations Limited Literacy of Parents in Native Language Poor Instructional Match Unaccepting Teachers and/or School Community Importance of Home Support… Factors Contributing to Delayed L2 Acquisition, cont. Deficit in phonological skills (both for L1 and L2) is indicative of dyslexia Later exposure to L2 Research shows that children who are exposed to L2 before age 3 have better reading performance than children exposed to L2 in 2nd and 3rd grade. Collier & Thomas’ L2 Acquisition Model Sociocultural Processes Cognitive Processes L2 Acquisition Academic Processes Linguistic Processes These components are interdependent, so if one is developed to the neglect of another, it may prove to be detrimental to the student’s overall growth and success. School psychologists should examiner every component when dealing with low academic performance in ELs. Importance of Native Language Basics of Language Acquisition Regardless of the dialect, in the first 5 years of life, all humans begin to develop a complex oral language system. Between ages 6-12, children continue acquiring increasinglycomplex vocabulary, pragmatics, semantics, syntax, etc. Through formal education, reading and writing are added to the language system in addition to listening and speaking. Basics of Language Acquisition When children (or adults) are required to acquire a second language, they use the same innate process they used to acquire their first language. Cross-Linguistic Transfer If students have certain strengths in their L1, and those strengths are known to transfer across languages, then we can expect that the students will develop those proficiencies in their L2 as their L2 proficiency develops Domains of Cross-Linguistic Transfer: Phonological Awareness Syntactic Awareness Functional Awareness Decoding Use of Formal Definitions and Decontextualized Language Importance of Native Language Literacy In U.S. schools where all instruction is given in English, EL student with no schooling in their first language take 7-10 years or more to reach age and grade-level norms of their native English-speaking peers. Immigrant students who have had 2-3 years of first language schooling in their home country before they come to the U.S. take at least 5-7 years to reach typical native-speaker performance. Source: Collier, V. (1995). Acquiring a second language for school (electronic version.) Direction in Language and Education, 1(4). Good to Know… Concepts learned well in one language can be transferred to another Knowledge of phonemes may be absent for English Learners Training helps Children with no phonological problems catch up with their peers in phonological processing in 1 to 2 years Good to Know… Studies show that students whose primary language is alphabetic with letter-sound correspondence (e.g., Spanish) have an advantage in learning English as opposed to students who speak non-alphabetic languages (e.g., Chinese). Given what we know… Look for patterns… Whenever possible, look for patterns of language acquisition difficulties in student’s native language. Play detective… Obtain records from the student’s native country, review current records, interview parents, etc. Given what we know… School psychologists should encourage EL students and their families to continue L1 development. Cummins (1981) proposed that the best way for students to develop CALP in L2 is to first develop CALP in L1. Overrepresentation of ELs in Special Ed. EL Students and Overrepresentation ELs are twice as likely to be identified as having a learning disability, intellectual disability or speech/language impairment as non-ELs. For this project, we will focus on SLD and ID. Specific Learning Disability SLD & SLI are the most frequent eligibility categories under which EL students qualify for special education Difficulties with Assessing ELs with SLD Lack of appropriately standardized tests for the EL population Test items are culturally loaded so results cannot be taken at their face value Difficult to discern between an EL’s language deficiencies and learning disability Factors Contributing to Difficulties when Assessing ELs with LD Typical EL students and EL’s with LD share many characteristics: Poor comprehension Difficulty following directions Syntactical and grammatical errors Difficulty completing tasks Poor Motivation Low Self-Esteem Poor Oral Language Skills It has been suggested that linguistic diversity may increase assessment errors and reduce the reliability of assessments Lack of teachers trained in bilingual and multicultural education to meet and assess EL students’ needs Mistaking basic interpersonal communication skills (BICS) for cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP) So what’s the big deal? Research shows that inappropriate placement into special education programs results in academic regression over time (Garcia & Ortiz, 2004) Intellectual Disability EL students are also overrepresented in this category. This may be due to: lack of understanding by the IEP team of the typical timeline of language acquisition for ELs lack of instruction that has research-based evidence showing its effectiveness for ELs and use of assessment methods that lack reliability and validity for ELs as a population Current Methods of Assessment Assessment in English Pro’s: Con’s: Accommodations can be made (to test itself or to test procedure) to provide a more valid picture of the EL student’s abilities: Provides information about the student’s level of functioning/ability in an English-speaking environment Student’s may not thoroughly understand task instructions or particular test items due to limited English proficiency Compromises test validity: Student not represented in the norm group Changing/simplifying language to improve understanding of test instructions breaks standardization Students demonstrate slower processing speeds and are more easily distracted during assessments conducted in a language with which they are less familiar ELs performed one full standard deviation below native speakers Assessment in English Checklist of Test Accommodations Before Conducting the Test: Make sure that the student has had experience with content or tasks assessed by the test Modify linguistic complexity and text direction Prepare additional example items/tasks During the Test: Allow student to label items in receptive vocabulary tests to determine appropriateness of stimuli Ask student to identify actual objects or items if they have limited experience with books and pictures Use additional demonstration items Record all responses and prompts Test beyond the ceiling Provide additional time to respond/extra testing time Reword or expand instructions Provide visual supports Provide dictionaries Read questions and explanations aloud (in English) Put written answers directly in test booklet (modified from Szu-Yin & Flores, 2011) Assessment in Native Language Pro’s: May provide a more accurate inventory of student’s knowledge and skills Interpreters can be utilized to facilitate testing if psychologist does not speak the student’s native language Con’s: Language-specific assessment for each and every student are not available If they are unfamiliar with the educational context, using interpreters may compromise test validity School psychologist must speak the language of the student Normed on the population of monolingual speakers from that country Nonverbal Assessment Pro’s: Attempts to eliminate language proficiency as a factor in the assessment May provide a better/more accurate estimate of student’s cognitive abilities Con’s Often does not fully eliminate language Offers a limited perspective of a student’s academic potential Fails to provide information about linguistic proficiency in student’s native language or in English Cultural context is still embedded within the test items Cannot measure certain abilities (language arts, reading, etc.) Best Practices Best Practices & Interventions Four methods will be presented: 1. 2. 3. 4. Assessment in both native language and English The Multidimensional Assessment Model for Bilingual Individuals (MAMBI) Cultural-Language Interpretive Matrix (C-LIM) Alvarado’s four steps to bilingual assessment Alternative Assessment for ELs Evidence-Based Interventions Assess in L1 and L2 Assess both in the native language and in English. English language performance: Will help the practitioner understand the student’s current level of English proficiency, and Will give the IEP team an idea of how well the student can understand the every day English instruction in the classroom Native language performance: Will help the practitioner gain a better understanding of the student’s knowledge and skills Multidimensional Assessment Model for Bilingual Individuals (MAMBI) A grid that provides 9 profiles for a practitioner to choose from and takes into consideration 4 major variables about the student: The student’s proficiency in L1 and L2 Current grade level Type of educational program Length of student’s instruction in the program Once these variables are accounted for, the practitioner is left with the method of evaluation that is most likely to yield valid results: Nonverbal Assessment Assessment primarily in L1 Assessment primarily in L2 Bilingual assessment both in L1 and L2 MAMBI: Step 1 Assess the student’s proficiency in L1 and L2 Can be obtained from multiple sources, including: CALP score from the Woodcock-Johnson Munoz Language Survey or the Bilingual Verbal Ability Test (BVAT) Teacher and parent questionnaires Observations (classroom, playground/recess, home, etc.) Formal and informal interviews with parents, teachers, and student. Once this information is obtained, choose one of the 9 profiles from the Language Profiles of English Learners Table Language Profile L1 Proficiency Level L2 Proficiency Level Profile 1 Minimal Minimal Profile 2 Emergent Minimal Profile 3 Profile 4 Profile 5 Profile 6 Profile 7 Profile 8 Profile 9 Fluent Minimal Emergent Fluent Minimal Emergent Fluent Description CALP level in L1 and L2 are both in the 1-2 range – individual has no significant dominant language, and proficiency and skills in both languages are extremely limited. CALP level in L1 is in the 3 range and English is in the 1-2 range – individual is relatively more dominant in L1, and proficiency and skills are developing but limited; L2 proficiency and skills remain extremely limited. Minimal CALP level in L1 is in the 4-5 range and L2 is in the 1-2 range – individual is highly dominant and very proficient in L1; L2 proficiency and skills remain extremely limited. Emergent CALP level in L1 is in the 1-2 range and L2 is in the 3 range – individual is relatively more dominant in L2, with developing but limited proficiency and skills; L1 proficiency and skills are extremely limited. Emergent CALP level in L1 is in the 3 range and L2 is in the 3 range – individual has no significant language dominance and is developing proficiency and skills in both but is still limited in both. Emergent CALP level in L1 is in the 4-5 range and L2 is in the 3 range – individual is relative more dominant in L1, with high proficiency and skills; L2 proficiency and skills are developing but still limited. Fluent CALP level in L1 is in the 1-2 range and L2 is in the 4-5 range – individual is highly dominant and very proficient in L2; L1 proficiency and skills are extremely limited. Fluent CALP level in L1 is in the 3 range and L2 is in the 4-5 range – individual is dominant and very proficient in L2; L1 language proficiency and skills are developing but limited. Fluent CALP level in L1 and L2 are both in the 4-5 range – individual has no significant dominant language and is very fluent and very proficient in both. Source: Ochoa & Ortiz, 2005 MAMBI: Step 2 Find out what kind of program the student has been a part of in the past and is in currently. Choose from one of the three educational circumstances: 1. 2. 3. Bilingual education in lieu of, or in addition to receiving ESL services Previously been in bilingual education but who are now receiving English-only instruction or ESL services All instruction has occurred in an English-only program with or without ESL services MAMBI: Steps 3 & 4 Step 3: Know the student’s current grade level and select between two options: – 4th grades 5th – 7th grades K Step 4: Select the appropriate testing modality from the MAMBI grid which include four options: Nonverbal assessment, assessment in L1, assessment in L2, or assessment in L1 and L2 MAMBI Grid The Ochoa and Ortiz Multidimensional Assessment Model for Bilingual Individuals, Ochoa, S.H. & Ortiz, S.O. 2005. Copyright Guilford Press. Reprinted with permission of The Guilford Press. Culture-Language Test Classifications and the Culture-Language Interpretive Matrix C-LTC- a data-driven classification system for the subtests of cognitive assessment measures based on two critical test dimensions: Degree of Cultural Loading Degree of Linguistic Demand Each dimension has three levels or degrees which are “High”, “Moderate”, and “Low” How were the C-LTC & C-LIM Developed? The two dimensions of these tools were chosen due to their repeated identification in the research literature as factors having significant relationships to test performance for culturally and linguistically diverse populations as well as factors which could invalidate test results. Classifications within these tools are data-driven and organized by the empirical studies on testing done in English with bilingual individuals. Purpose of the C-LTC & C-LIM To evaluate the extent of the effect of differences in language proficiency and level of acculturation on the validity of scores obtained from standardized tests. Seeks to identify tests with the lowest levels of cultural loading and linguistic demand to help us choose tests with the highest likelihood of valid scores. NOT DISGNOSTIC TOOLS IN AND OF THEMSELVES!!! CHC Culture-Language Interpretive Matrix Pattern of Expected Performance for Individuals From Diverse Cultural and Linguistic Backgrounds DEGREE OF LINGUISTIC DEMAND PERFORMANCE LEAST AFFECTED MODERATE HIGH INCREASING EFFECT OF LANGUAGE DIFFERENCE MODERAT E HIGH DEGREE OF CULTURAL LOADING LOW LOW INCREASING EFFECT OF CULTURAL DIFFERENCE PERFORMANCE MOST AFFECTED (COMBINED EFFECT OF CULTURAL & LANGUAGE DIFFERENCES) Flanagan, D. P., Ortiz, S. O., & Alfonso, V. C., Essentials of cross-battery assessment (Vol. 84). Copyright John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [2013, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.]. This material is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. General Guidelines for Expected Patterns of Test Performance for Diverse Individuals Slightly Different: Includes individuals with high levels of English language proficiency (e.g., advanced BICS/emerging CALP) and high acculturation, but still not entirely comparable to mainstream U.S. English speakers. Examples include individuals who have resided in the U.S. for more than 7 years or who have parents with at least a high school education, and who demonstrate native-like proficiency in English language conversation and solid literacy skills. Different: Includes individuals with moderate levels of English language proficiency (e.g., intermediate to advanced BICS) and moderate levels of acculturation. Examples include individuals who have resided in the U.S. for 3-7 years and who have learned English well enough to communicate, but whose parents are limited English speakers with only some formal schooling, and improving but below grade level literacy skills. Markedly Different: Includes individuals with low to very low levels of English language proficiency (e.g., early BICS) and low or very low levels of acculturation. Examples include individuals who recently arrived in the U.S. or who may have been in the U.S. 3 years or less, with little or no prior formal education, who are just beginning to develop conversational abilities and whose literacy skills are also just emerging. Flanagan, D. P., Ortiz, S. O., & Alfonso, V. C., Essentials of cross-battery assessment (Vol. 84). Copyright John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [2013, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.]. This material is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. General Guidelines for Expected Patterns of Test Performance for Diverse Individuals, cont’d. Degree of Linguistic Demand Low Moderate High Degree of Cultural Loading Low Moderate High Slightly Different: 3-5 points Slightly Different: 5-7 points Slightly Different: 7-10 points Different: 5-7 points Different: 7-10 points Different: 10-15 points Markedly Different: 7-10 points Markedly Different: 10-15 points Markedly Different: 15-20 points Slightly Different: 5-7 points Slightly Different: 7-10 points Slightly Different: 10-15 points Different: 7-10 points Different: 10-15 points Different: 15-20 points Markedly Different: 10-15 points Markedly Different: 15-20 points Markedly Different: 20-25 points Slightly Different: 7-10 points Slightly Different: 10-15 points Slightly Different: 15-20 points Different: 10-15 points Different: 15-20 points Different: 20-30 points Markedly Different: 15-20 points Markedly Different: 20-25 points Markedly Different: 25-35 points Flanagan, D. P., Ortiz, S. O., & Alfonso, V. C., Essentials of cross-battery assessment (Vol. 84). Copyright John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [2013, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.]. This material is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. Subtests of the WISC-IV Block Design Similarities Digit Span Picture Concepts Coding Vocabulary Letter-Number Sequence Matrix Reasoning Comprehension Symbol Search Picture Completion Cancellation Information Arithmetic Word Reasoning Culture-Language Test Classifications: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fourth Edition Degree of Linguistic Demand LOW MODERATE BLOCK DESIGN (BD) AND BD NO TIME BONUS CODING DIGIT SPAN SYMBOL SEARCH HIGH LETTER-NUMBER SEQUENCING ARITHMETIC PICTURE CONCEPTS PICTURE COMPLETION HIGH Degree of Cultural Loading LOW CANCELATION MATRIX REASONING MODERATE COMPREHENSION INFORMATION SIMILARITIES VOCABULARY WORD REASONING Flanagan, D. P., Ortiz, S. O., & Alfonso, V. C., Essentials of cross-battery assessment (Vol. 84). Copyright John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [2013, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.]. This material is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. Culture-Language Test Classifications: Bateria III Woodcock-Munoz Cognitiva MODERATE HIGH Degree of Cultural Loading LOW LOW Degree ofMODERATE Linguistic Demand HIGH Integracion de Sonidos Atencion Auditiva Reconocimiento de Dibujos Palabras Incompletas Analisis-Sintesis Rapidez en el Decision Relaciones Espaciales Formacion de Conceptos Memoria de Trabajo Auditivo Cancelacion de Pares Planeamiento Memoria Para Palabras Fluidez de Recuperacion Inversion de Numeros Rapidez en la Identificacion de Dibjuos Pareo Visual Aprendizaje Visual-Auditivo Memoria Diferida – Aprendizaje Visual Auditivo Informacion General Comprension Verbal *Note: The subtests and their classifications as shown in this matrix have not been the subject of extensive empirical investigation. The classifications herein are drawn primarily from the work of J. E. Brown (2008, 2011) and users are referred to this source for additional information. The classifications offered herein are provided primarily for the purposes of continued research and exploration. As such, their use in evaluating the validity of obtained test results and their utility in making subsequent decisions regarding the effect of cultural and linguistic variables on the test performance of ELs cannot yet be recommended as meeting an evidence-based standard at this time. The matrix and graph are intended only to promote further research on the manner in which such variables affect test performance.. Flanagan, D. P., Ortiz, S. O., & Alfonso, V. C., Essentials of cross-battery assessment (Vol. 84). Copyright John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [2013, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.]. This material is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. Great tools to use, but… Using the C-LTC and C-LIM to evaluate validity of our test results is not sufficient to establish that a fair and unbiased assessment was completed. In order to be called a nondiscriminatory assessment the entire assessment process must follow a comprehensive framework. Alvarado’s 4 Steps to Bilingual Special Education Evaluation 1. 2. 3. 4. Gathering of student information Oral language proficiency and dominance testing Achievement testing Cognitive testing The language or languages of each step is dictated by the individual student’s language exposure, language dominance, and academic background and by the objective of the assessment. Determining Language Dominance Alvarado’s model for determining language dominance: Using a test that has two language forms that have been statistically equated in order to allow comparison of abilities and skills between those two languages. Two steps are proposed: 1: the core language of the cognitive battery is determined on the basis of the student’s dominant language 2: the appropriate scale is selected on the basis of the student’s language status in his/her dominant language In the Woodcock tests, the Batería III COG is statistically equated to the WJ III COG. Likewise the Batería III APROV is statistically equated to the WJ III ACH. Informal Ways to Assess Language Dominance Language student prefers talking in Which language produces better phrasing Speech therapists can test What movies do they watch (English or Spanish) Friends on playground Alternative Assessment Methods How CBM Can Help EL Students Determine whether instructional programs are addressing needs of EL population as a whole Inform instructional decisions for struggling EL students Compare target students to EL and non-EL peers Using CBM/RTI with ELs Used to: Screen for students at risk of learning difficulties Monitor progress of all students Monitor progress of selected students Determine whether instruction/intervention is effective Making special education decisions Using CBM/RTI with ELs Useful but needs more research!!! Some current research on the use of reading CBM/RTI methods Little research on CBM for math skills with ELs Provides more qualitative than quantitative data Doesn’t work well if using the discrepancy model Challenges With CBM/RTI and ELs Difficulty in determining: benchmarks expectations appropriate growth rate Lack of growth can be due to variety of factors, such as: Language SES Instruction True Learning Disability Interventions The following reading interventions are recommended by What Works Clearinghouse for use with EL students: Enhanced Proactive Reading Read Well SRA Reading Mastery/SRA Corrective Reading Common elements in the above intervention programs: formed a central aspect of daily reading instruction between 30 and 50 minutes to implement per day intensive small-group instruction following the principles of direct and explicit instruction in the core areas of reading extensive training of the teachers and interventionists Interventions AIM for the BESt: Assessment and Intervention Model for the Bilingual Exceptional Student Incorporates pre-referral intervention, assessment, and intervention strategies Uses nonbiased measures Aims to improve academic performance for culturally and linguistically diverse students and aims to reduce inappropriate referrals to special education How? Use of instructional strategies proven to be effective with languageminority students Allows teachers flexibility to modify instruction for struggling students Supports teachers with a team of professionals Uses CBM and criterion-referenced tests to assess in addition to standardized test data Model holds promise for improving educational services provided to limited English-proficient students(Ortiz et al., 2011) Case Study #1: Jorge The Facts Age: 10 years old Grade: 5th Native language: Spanish Program: SDC Initial Eligibility Category: Significant Adaptive and Intellectual Disability Current Eligibility Category: Specific Learning Disability Case Study #1: Jorge Initial Evaluation 2005 Differential Ability Scales (DAS Preschool Version) (Average scores between 90-110) General Conceptual Ability: 59 Verbal: 55 Performance Standard Score: 62 Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales – Survey Edition (Average scores between 85-115) Communication: 63 Daily Living Skills: 65 Socialization: 70 Adaptive Behavior: 54 Eligibility: “Significant Adaptive and Intellectual Disability” Questions for Discussion What mistakes, if any, did the examiner make when assessing Jorge? Using the tools discussed in this training, come up with the best assessment method for Jorge. Case Study #1: Jorge Subsequent Evaluations 2008 Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd Edition (KABC-II) (Average scores between 85-115) The Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (ABAS-II) Behavior Assessment System for Children, 2nd Edition (BASC-2) Test of Auditory Processing Skills (TAPS-3) (Average scores between 85-115) Test of Word Reading Efficiency (TOWRE) (Average scores between 85-115) Sequential: 66 Simultaneous: 84 Learning: 86 Planning: 72 Knowledge: 72 Nonverbal Index: 76 Parent/Teacher Ratings: GAC: 41 / 57 Conceptual: 50 / 61 Social: 55 / 75 Practical: 42 / 51 Clinically Significant Areas: Parent – social skills, activities of daily living, functional communication Teacher – aggression Phonological: 73 Memory: 64 Cohesion: 73 Overall: 70 Sight Words: 75 Phonemic Decoding: 85 Case Study #1: Jorge Subsequent Evaluations 2011 Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd Edition (KABC-II) (Average scores between 85-115) Sequential: 74 Simultaneous: 105 Learning: 100 Planning: 93 Knowledge: 102 MPI: 90 Naglieri Nonverbal Ability Test- Individual Administration (NNAT-I) (Average scores between 85-115) General Ability: 91 Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (CTOPP) (Average scores between 90-110) Phonological Awareness: 91 Phonological Memory: 64 Rapid Naming: 79 Alternate Phonological Awareness: 76 Alternate Rapid Naming: 79 Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning (WRAML) (Average scores between 85-115) Verbal Memory: 80 Visual Memory: 106 Attention-Concentration: 57 General Memory: 74 Case Study #2: Miguel The Facts Age: 10 years old Grade: 5th Native language: Spanish Program: SDC Initial Eligibility Category: Speech and Language Impairment Current Eligibility Category: Intellectual Disability Case Study #2: Miguel Initial Evaluation 2011 Full Scale IQ (Standard Score): 67 Wechsler Nonverbal Scale of Abiltiy (Average standard scores between 90-110, TScores between 40-60) Subtest Scores (T-Scores) Matrices: 31 Object Assembly: 30 Coding: 39 Recognition: 35 Teacher Ratings The Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (ABAS-II) (Average standard scores between 90-109) Global Adaptive Composite score: 42 (Very Low) Conceptual Domain: 52 Practical Domain: 43 Social Domain: 55 Case Study #2: Miguel Initial Evaluation Bilingual Verbal Ability: 70 Bilingual Verbal Ability Test (Average standard scores between 90-109) English Language Proficiency: 63 CALP Level: 2 (Very Limited) Language Use Inventory Miguel was asked questions in both Spanish and English about what language he used in various environments (home, school, playground, etc.). He reportedly had a hard time understanding most of these questions but was able to communicate to the examiner that he used both English and Spanish at home. He also shared that he only spoke Spanish with his mother and that he preferred to speak in Spanish. Speaking – Early Intermediate California English Language Development Test Listening – Beginning Reading – Early Intermediate Writing – Beginning Questions for Discussion: What, if any, mistakes did the examiner make when assessing Miguel? Using the tools discussed in this training, come up with the best assessment method for Miguel. References Abedi, J. 2006. Psychometric issues in the EL assessment and special education eligibility. Teachers College Record, 108(11), 2282-2303. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00782.x Abedi, J., & Gandara, P. (2006). Performance of English language learners as a subgroup in a large-scale assessment: Interaction of research and policy. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practices, pp. 36-46. Alvarado, C.G. (n.d.). Bilingual special education evaluation of culturally and linguistically diverse individuals using Woodcock tests. Retrieved from http://www.educationeval .com/files/BilingualSpEdEvalofCLDIndividualsUsingWoodcockTests.doc Artiles, A. J., Rueda, R., Salazar, J. J., & Higareda, I. (2005). Within-group diversity in minority disproportionate representation: English language learners in urban school districts. Exceptional Children, 71, 283-300. Artiles, A. J., & Ortiz, A. A. (2002). Before assessing a child for special education, first assess the instructional program: A summary of language learners with special educational needs. Retrieved from http://www.misd.net/bilingual/ellandspedcal.pdf Baker, S. K., & Good, R. H. (1995). Curriculum-based measurement of English reading with bilingual Hispanic students: A validation study with second-grade students. School Psychology Review 24(4), 561-578. Batalova, J., & Terrazas, A. (2010). Frequently requested statistics on immigrants and immigration in the United States. Retrieved on October 21, 2013 from http://www.migrationinformation.org/USFocus/display.cfm?ID=818#1a References cont. Bentz, J. & Pavri, S. (2000). Curriculum-based measurement in assessing bilingual students: A promising new direction. Diagnostique 25(3), 229-248. Berko Gleason, J. (1993). The development of language (3rd ed.). New York: Macmillan. Brooks, K., Adams, S.R., & Morita-Mullaney, T. (2010). Creating inclusive learning commuinities for EL students: Transforming school principals’ perspectives. Theory Into Practice, 49(2), 145-151. Butler, F.A. & Stevens, R. (2001). Standardized assessment of the content knowledge of English language learners K-12: Current research trends and old dilemmas. Language Testing 18(4), 409-427. doi: 10.1191/026553201682430111 Bylund, J. (2011, January/February). Thought and second language: A Vygotskian framework for understanding BICS and CALP. NASP Communique, 39(5). California Department of Education (2004). California Code of Regulations (CCR), Title 5, 3023(b). Collier, V. P. (1995). Acquiring a second language for school. Direction in Language and Education, 1(4), 1-8. For National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education. Retrieved from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/files/rcd/BE020668/Acquiring_a_Second_Language_.pdf Collier, V. P., & Thomas, W. P. (1989). How quickly can immigrants become proficient in school English? Journal of Educational Issues of Language Minority Students, 5, 26-38. Cummins, J. (1981). Empirical and theoretical underpinnings of bilingual education. Journal of Education, 163, 16-30. De Valenzuela, J.S., Copeland, S.R., & Qi, C.H. (2006). Examining educational equity: Revisiting the disproportionate representation of minority students in special education. Exceptional Children 72(4), 425441. References cont. Dixon, L. Q., Chuang, H.-K., & Quiroz, B. (2012). English phonological awareness in bilinguals: a crosslinguistic study of Tamil, Malay and Chinese English-language learners. Journal of Research in Reading, 35(4), 372-392. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9817.2010.01471.x Ed-Data (2014). State of California Education Profile. Fiscal Year: 2012-13. Retrieved on February 17, 2014 from http://www.eddata.k12.ca.us/App_Resx/EdDataClassic/fsTwoPanel.aspx?#!bottom=/_layouts/EdDataClassic/profile.asp ?Tab=1&level=04&reportNumber=16#englishlearners Ellis, R. (1985). Understanding second language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Flanagan, D. P., & Ortiz, S. O. (2001). The culture-language interpretive matrix (C-LIM). In Contemporary intellectual assessments (third edition), ed. Flanagan, D. P., & Harrison, P. L., 548. New York: Guilford Press. Garcia, S. B., & Ortiz, A. A. (2004). Preventing inappropriate referrals of language minority sutdents to special education. National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition: Washington, D.C. Gonzalez, V., Brusca-Vega, R., & Yawkey, T. (1997). Assessment and instruction of culturally and linguistically diverse students with or at-risk of learning problems: From research to practice. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Guajardo Alvarado, C. (2011). Best practices in the special education evaluation of culturally and linguistically diverse students. Retrieved from http://www.educationeval.com/files/ Best_Practices_2011.pdf Huang, J., Clarke, K., Milczarski, E., & Raby, C. (2011). The assessment of English language learners with learning disabilities: issues, concerns, and implications. Education, 131(4), 732-739. References cont. Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (2004). Pub. L. No. 108-446, (2004). Retrieved [summary] March 3, 2014, from http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d108:HR01350:@@@L&summ2=m& Larry P. vs. Riles. Citation. 793 F.2d 969 (9th Cir.October 16, 1979). As retrieved 3/3/2014 from http://scholar.google.com Liu, L. L., Benner, A. D., Lau, A S., & Kim, S. Y. (2009). Mother-adolescent language proficiency and adolescent academic and emotional adjustment among Chinese American Families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 572586. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9358-8 Mueller, T. G., Singer, G. S. H., & Carranza, F. D. (2006). A national survey of the educational planning and language instruction practices for students with moderate to severe disabilities who are English language learners. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 31(3), 242-254. National Association of School Psychologists (2010). Principles for professional ethics. Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/standards/2010standards/ 1_%20Ethical%20Principles.pdf National Association of School Psychologists. (2012). Racism, prejudice, and discrimination. [Position Statement]. National Council of Teachers of English. (2008). English language learners: A policy research brief. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/PolicyResearch/ELResearchBrief.pdf Ortiz, A. A., & Maldonado-Colon, E. (1986). Reducing inappropriate referrals of language minority students to special education. In Bilingualism and learning disabilities, ed. Willing, A. C., & Greenberg, H. F., 37-50. New York: American Library. Ortiz, A. A., & Yates, J. R. (2001). A framework for serving English language learners with disabilities. Journal of Special Education Leadership, 14(2), 72-80. References cont. Ochoa, S.H. (2005a). Representation of Diverse Students in Special Education. In Assessing culturally and linguistically diverse students: A practical guide (pp. 15-41). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. Ochoa, S.H. (2005b). Bilingual education and second-language acquisition. In Rhodes, R. L., Ochoa, S. H, & Ortiz, S. O. (Eds.), Assessing culturally and linguistically diverse individuals: A practical guide (pp. 57-75). New York: Guilford Press. Ochoa, S.H., Gonzalez, D., Galarza, A., & Guillemard, L. (1996). The training and use of interpreters in bilingual psycho-educational assessment: An alternative in need of study. Diagnostique, 21(3), 19-40. Ochoa, S. H., & Ortiz, S. O. (2005). Cognitive assessment of culturally and linguistically diverse individuals: An integrative approach. In Rhodes, R. L., Ochoa, S. H, & Ortiz, S. O. (Eds.), Assessing culturally and linguistically diverse individuals: A practical guide (pp. 168-201). New York: Guilford Press. Ochoa, S.H., Riccio, C. A., Jimenez, S., Garcia de Alba, R., & Sines, M. (2004). Psychological assessment of limited English proficient and/or bilingual students: An investigation of school psychologists’ current practices. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 22, 93-105. Ortiz, S.O., Ochoa, S.H., & Dynda, A.M. (2012). Testing with culturally and linguistically diverse populations: Moving beyond the verbal-performance dichotomy into evidence-based practice. In D.P. Flanagan & P.L. Harrison (Eds.), Contemporary intellectual assessment: Theories, tests, and issues (3rd ed.) (pp.526-552). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. Petitto, L.A. (2009). New discoveries from the bilingual brain and mind across the life span: Implications for education. Mind, Brain, and Education, 3, 185-197. Rhodes, R.L. (2005a). Legal and ethical requirements for the assessment of culturally and linguistically diverse students. In Rhodes, R. L., Ochoa, S. H, & Ortiz, S. O. (Eds.), Assessing culturally and linguistically diverse individuals: A practical guide (pp. 42-56). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. Rhodes, R.L. (2005b). Use of interpreters in assessment and practice. In Rhodes, R. L., Ochoa, S. H, & Ortiz, S. O. (Eds.), Assessing culturally and linguistically diverse individuals: A practical guide (pp. 91-102). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. Rhodes, R. L., Ochoa, S. H., & Ortiz, S. O. (2005). Assessing culturally and linguistically diverse students: A practical References cont. Richards-Tutor, C., Solari, E.J., Leafstedt, J.M., Gerber, M.M., Filippini, A., & Aceves, T.C. (2012). Response to intervention for English learners: Examining models for determining response and nonresponse. Assessment for Effective Intervention 38(3), 72-84. doi:10.1177/1534508412461522 Sheng, Z., Sheng, Y., & Anderson, C.J. (2011). Dropping out of school among EL students: Implications to schools and teacher education. Clearing House, 84(3), 98-103. Sotelo-Dynega, M., Cuskley, T., Geddes, L., McSwiggan, K., & Soldano, A. (2011). Cognitive assessment: A survey of current school psychologists’ practices. Poster presented at the National Association of School Psychologists, San Francisco. Sullivan, A. L. (2011). Disproportionality in Special Education Identification and Placement of English Language Learners. Exceptional Children, 77(3), 317-334. Texas Council for Developmental Disabilities (2013). Special Education Public Policy. Retrieved on February 17, 2014 from http://www.projectidealonline.org/v/special-education-public-policy/ Thomas, A. & Grimes, J. (eds.) (2008). Appendix II – Guidelines for the provision of school psychological services. Best practices in school psychology V. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Thomas, W. P., & Collier, V. P. (2002). A national study of school effectiveness for language minority students’ long-term academic achievement: Executive summary. Santa Cruz, CA: Center for Research on Education, Diversity, and Excellence. Retrieved on November 4, 2011 from http://www.usc.edu/dept/education/CMMR/ CollierThomasExReport.pdf U.S. Census Bureau (2010). Census population profile maps. Retreived on October 21, 2013 from http://www.census.gov/geo/www/maps/2010_census_profile_maps/census_profile_2010_main.html U.S. Department of Education (2006a). Topic: part c amendments in IDEA 2004. Retrieved on March 3, 2014 from http://idea.ed.gov/explore/view/p/ %2Croot%2Cdynamic%2CTopicalBrief%2C13%2C U.S. Department of Education (2006b). DHEW memo regarding language minority children. From the Office of Civil Rights. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/about/ offices/list/ocr/docs/lau1970.html U.S. Department of Education. (2006c). Specific learning disability, 34 CFR 300.8(c) (10). Retrieved from http://idea.ed.gov/explore/view/p/ %2Croot%2Cstatute%2CI%2CA%2C602%2C30%2C Protections for Children not Determined Eligible for Special Education and Related Services, 34 CFR § 300.534 (2006). Worthington, E., Maude, S., Hughes, K., Luze, G., Peterson, C., Brotherson, M., Bruna, K., & Luchtel, M. (2011). A qualitative examination for the challenges, resources, and strategies for serving children learning English in Head Start. Early Childhood Education, 39, 51-60.