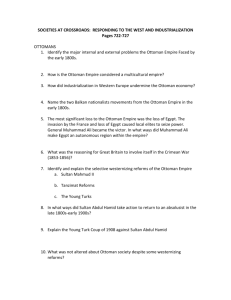

5 • The Era of the Tanzimat, 1839-71

advertisement

5 • The Era of the Tanzimat, 1839-71

Sultan Mahmut II died of tuberculosis on 30 June 1839, before

the news of the Ottoman defeat by the Egyptians at Nizip had

reached Istanbul. His elder son, Abdiilmecit, who succeeded

him, was to reign from 1839 to 1861. Mahmut’s death did not

mark the beginning of a period of reaction, as Selim Ill’s

death had in 1807. The centralizing and modernizing reforms

were continued essentially in the same vein for another

generation. Indeed, the period from 1839 to 1876 is known in

Turkish historiography as the period of the Tanzimat (reforms)

par excellence, although one could well argue that in fact the

period of the reforms ended in 1871. The term Tanzimat-i

Hayriye (beneficial reforms) had been used even before 1839,

for instance in the imperial order establishing the Supreme

Council for Judicial Regulations (Meclis-i Vala-i Ahkam-i

Adliye).' This illustrates the continuity between the period

of Mahmut II and that of his successors. The main difference

was that the centre of power now shifted from the palace to

the Porte, the bureaucracy. In order to create a strong and

modem apparatus with which to govern the empire, Mahmut had

helped to start transforming the traditional scribal

institution into something resembling a modem bureaucracy,

thereby so strengthening it that his weaker successors lost

control of the bureaucratic apparatus for much of the time.

The reform edict of GOlhane

Under Mahmud’s successors foreign, especially British,

influence on policy-making in Istanbul vastly increased. For a

generation after the second Egyptian crisis, Britain supported

the Ottoman Empire’s continued existence as a buffer against

what was perceived in London as dangerous Russian

expansionism. The Russophobe Stratford Canning (from 1852 Lord

Stratford de Redcliffe), who was British ambassador in

Istanbul from 1841 to 1858 and was on close terms with many of

the leading Ottoman reformers, played a crucial role in this

British support.

The beginnings of the Tanzimat coincided with the attempts to

solve

THE ERA OF THE TANZIMAT, 1839-71

51

the second Egyptian crisis. When Ottoman fortunes were at

their lowest ebb, on 3 November 1839, an imperial edict

written by the leading reformer and foreign minister, Re§it

Pasha, but promulgated in the name of the new sultan, was read

outside the palace gates (at the Square of the Rose Garden,

hence its name Gulhane Hatt-i §erifi (the Noble Edict of the

Rose Garden) to an assembly of Ottoman dignitaries and foreign

diplomats. It was a statement of intent on the part of the

Ottoman government, promising in effect four basic reforms:

• The establishment of guarantees for the life, honour and

property of the sultan’s subjects;

• An orderly system of taxation to replace the system of tax

farming;

• A system of conscription for the army; and

• Equality before the law of all subjects, whatever their

religion (although this was formulated somewhat ambiguously

in the document).2

Controversy has raged ever since its promulgation over the

character and especially the sincerity of the edict and the

Tanzimat policies based on it. It is undoubtedly true that the

promulgation of the edict at that specific time was a

diplomatic move, aimed at gaining the support of the European

powers, and especially Britain, for the empire in its struggle

with Mehmet Ali. It is equally true, however, that the text

reflected the genuine concerns of the group of reformers led

by Re?it Pasha. The promised reforms were clearly a

continuation of Mahmut II’s policies. The call for guarantees

for the life, honour and property of the subjects, apart from

echoing classic liberal thought as understood by the Ottoman

statesmen who had been to Europe and knew European languages,

also reflected the Ottoman bureaucrats’ desire to escape their

vulnerable position as slaves of the sultan. Taxation and

conscription, of course, had been two of Mahmut’s most urgent

concerns. The promise of equal rights to Ottoman Christians,

ambiguously as it was formulated, was certainly meant in part

for foreign consumption. On the other hand, it is clear that

Re§it Pasha and a number of his colleagues believed, or at

least hoped, that it would halt the growth of nationalism and

separatism among the Christian communities and that it would

remove pretexts for foreign, especially Russian, intervention.

In the short run the Gulhane edict certainly served its

purpose, although it is hard to say how much it contributed to

the decision of the powers to save the empire.

A solution to the Egyptian crisis

The defeat at Nizip had left the empire practically

defenceless and it

52

TURKEY: A MODERN HISTORY

would have had to give in to the demands of Mehmet Ali

(hereditary possession of Egypt, Syria and Adana) had not the

great powers intervened. Britain reacted quickly, giving its

fleet orders to cut communications between Egypt and Syria and

taking the initiative for contacts between the five major

powers (Russia, Austria, Prussia, France and Britain itself).

Diplomatic consultations lasted for over a year, with Russia

and Britain jointly pressing for an Egyptian evacuation of

Syria, while France increasingly came out in support of Mehmet

Ali. In the end, the other powers despaired of getting French

cooperation and on 15 July 1840 Russia, Prussia, Austria and

Britain signed an agreement with the Porte envisaging armed

support for the sultan. Late in 1840 the British navy

bombarded Egyptian positions in and around Beirut and landed

an expeditionary force, which, in conjunction with widespread

insurrections against his oppressive rule, forced Ibrahim

Pasha to withdraw from Syria. Diplomatic haggling went on for

some time longer, but basically the issue had now been

settled. In June 1841 Mehmet Ali accepted the loss of his

Syrian provinces in exchange for the hereditary governorship

of Egypt, which remained nominally part of the Ottoman Empire

until 1914.

Internal unrest and international politics

With the end of the second Egyptian crisis a noticeable

lessening of tension in the Middle East set in. The

fundamental problems of the empire, caused by rising tension

between the different nationalities and communities, which the

central government was unable to solve or control, had not

gone away, but for about 15 years they did not lead to largescale intervention on the part of the great powers of Europe.

The most violent inter-communal conflict of these years was

fought out in the Lebanon. The strong man of the area was the

Emir Bashir II, who belonged to the small religious community

of the Druzes,3 but had converted to Christianity and ruled

the Lebanon from his stronghold in the Shuf mountains for 50

years. He had linked his fate closely to that of the Egyptian

occupation forces, and when the latter had to leave Syria, his

position became untenable and he was ousted by his enemies

among the Druze tribal chiefs. After his demise in 1843, the

Ottoman government introduced a cantonal system, whereby

Lebanon north of the Beirut-Damascus highway was governed by a

Christian kaymakam (governor), while the area to the south of

the road was ruled by a Druze one, both under the jurisdiction

of the governor-general of Sidon, whose seat was now moved to

Beirut.

Because this division took no account of the mixed character

of the population in the south and the north, tensions soon

rose and in 1845

THE ERA OF THE TANZIMAT, 1839-71

53

they erupted in large-scale fighting, with the Druzes burning

down numerous Maronite Christian villages. Under pressure from

the powers — the French had established a de facto

protectorate over the Maronite Christians of the Lebanon (who

were uniate, that is, they recognized the pope and were

therefore officially regarded as Catholics), the British over

the Druzes, and the Russians over the Orthodox Christians the Ottomans severely punished the Druze leaders and set up

consultative assemblies representing the communities in both

cantons. This time the powers refrained from direct

intervention.

The Crimean War

The one great international conflict of these years, the

Crimean War (1853—56), had as its ostensible cause a dispute

over whether the Catholic or the Orthodox Church should

control the holy places in Palestine, especially the Church of

the Nativity in Bethlehem. France interceded on behalf of the

Catholics, while Russia defended the rights of the Orthodox.

The Catholic Church had been granted pre-eminence in 1740, but

the fact that many times more Orthodox than Catholic pilgrims

visited the holy land over time strengthened the Orthodox

Church’s position. France, supported by Austria, now demanded

reassertion of the pre-eminence of the Catholics. Russia

wanted the status quo to remain in force. The bewildered Porte

tried to please everyone at the same time.

The Teal reasons behind the aggressive attitude of France

and Russia were almost wholly domestic. Both the newly

established Second Republic in France, headed by Napoleon

Bonaparte (soon to be Emperor Napoleon III), and the Russian

tsar were trying to gain popular support by appealing to

religious fervour.

A dangerous escalation began when, on 5 May 1853, the

Russian envoy to Istanbul demanded the right to protect not

only the Orthodox Church (a claim based on a very partisan

reading of the privileges that had been granted in 1774) but

also the Orthodox population of the empire, more than a third

of its inhabitants. Supported by the French and British

ambassadors, the Porte refused to give in. Russia announced it

would occupy the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia if

the Porte did not accept its demands, and in July its troops

crossed into the principalities. A last-minute attempt at

mediation by France, Britain, Austria and Prussia failed. The

Ottomans demanded the evacuation of the principalities and,

when this was not forthcoming, declared war on Russia in

October. Under pressure from violently anti-Russian public

opinion and from the French government, the British cabinet

now opted for war and on 28 March 1854 war was officially

declared. None of the

54

TURKEY: A MODERN HISTORY

great powers wanted war, but all had backed themselves into a

comer they could not leave without serious loss of face.

Austria’s attitude in the conflict had been ambivalent from

the beginning and gradually became more and more anti-Russian,

so much so that the risk of an Austrian attack forced the

Russians to withdraw from the principalities in July. So the

French/British expeditionary force, which was sent to the

Levant in the expectation of having to fight in the Balkans,

was left without a target and landed in the Crimea instead,

hence ‘the Crimean War’. The war brought nobody much credit or

profit. The allies’ only major success was the taking of the

Russian fortress city of Sebastopol, but the price paid in

terms of suffering and casualties during the winter of 1854—5

(when Florence Nightingale reorganized the hospital the

British army had established in the Selimiye barracks in the

Istanbul suburb of Uskudar) was very high. In 1855, therefore,

all the belligerents were ready to talk. A peace conference

was held in Paris in February-March 1856 and produced a treaty

that embodied the main demands of France, Britain and Austria.

Although the war had been fought to defend the Ottoman

Empire, it was not consulted officially on the peace terms and

had to accept them as they were. The most important items in

the peace treaty were:

• Demilitarization of the Black Sea (also on the Turkish

side!);

• An end to Russian influence in Moldavia and Wallachia; and

• A guarantee of the independence and integrity of the Ottoman

Empire on the part of all the major European powers.

As a signatory to the Treaty of Paris the empire was now

formally admitted to the ‘Concert of Europe’, the Great

Powers’ system that had since Napoleon’s defeat and the

Congress of Vienna tried to maintain the European balance of

power. The financial and military weakness of the Ottomans

meant, however, that they remained an object of European

diplomatic intrigue rather that an active participant in it. A

new reform decree elaborating promises made in 1839 and

largely dictated by the French and British ambassadors in

Istanbul, was published to coincide with the peace conference

and to boost Ottoman prestige. The European powers officially

took note of the declaration and stated that it removed any

pretext for European intervention in relations between the

sultan and his subjects.4 This guarantee would prove a dead

letter.

The Crimean War was to have far-reaching consequences for

reforms within the empire and for its finances, but we shall

come to those later. For now, the integrity of the empire was

indeed saved and it would be another 20 years before its

existence was threatened again.

THE ERA OF THE TANZIMAT, 1839 -71

55

The Eastern Question again

In the meantime the old pattern of the politics and diplomacy

of the Eastern Question took shape again. As in the Serbian,

Greek and Lebanese crises, the pattern was basically always

the same: the discontent of (mostly Christian) communities in

the empire erupted into regional insurrections, caused partly

by bad government and partly by the different nationalisms

that were spreading at the time. One of the powers then

intervened diplomatically, or even militarily, to defend the

position of the local Christians. In the prevailing conditions

of interpower rivalry this caused the other major powers to

intervene to reestablish ‘the balance of power’. Usually, the

end result was a loss of control on the part of the central

Ottoman government.

This was what happened when the problems between Maronite

Christians and Druzes in Lebanon developed into a civil war

again in 1860. Maronite peasants, supported by their clergy,

revolted against their landlords (both Maronite and Druze) and

Druze fighters intervened, killing thousands of Maronite

peasants. Shortly afterwards, in July 1860, a Muslim mob,

incited by Druzes, killed more than 5000 local Christians in

Damascus. This caused the Powers to intervene on the

initiative of France. An expeditionary force, half of which

France supplied, landed in Beirut, despite Ottoman efforts to

pre-empt its arrival by draconic disciplinary measures.

France’s efforts to restructure the entire administration of

Syria were then blocked by the Porte with British support. In

the end, the mainly Christian parts of the Lebanese coast and

mountains became an autonomous province under a Christian

mutasarrif (collector), who had to be appointed with the

assent of the Powers.

The pattern was repeated when a revolt broke out in Crete in

1866. What began as a protest against Ottoman mismanagement of

affairs on the island, turned into a nationalist movement for

union with Greece. The conflict aroused public opinion both in

Greece, where volunteers were openly recruited for the

struggle on the island, and among the Muslims in the Ottoman

Empire (Crete had a significant Muslim minority) and by 1867

the two countries were on the brink of war. Russia, where

solidarity with the Greek Orthodox subjects of the sultan was

widely felt, urged European intervention on behalf of the

rebels and the cession of Crete to Greece, but the hesitations

of the other powers prevented the Powers from taking direct

action. Their combined pressure forced the Porte to declare an

amnesty for the rebels and to announce reforms in the

provincial administration of Crete giving the Christians more

influence, but foreign intervention went no further and by the

end of 1868 the rebellion was at an end.

In the Balkans, meanwhile, nationalist fervour was also

spreading,

56

TURKEY: A MODERN HISTORY

encouraged by the rise of the ‘pan-Slav’ movement in Russia

(the influential Russian ambassador in Istanbul, Ignatiev, was

an ardent supporter) and with Serbia as the epicentre of

agitation. When revolts broke out among the Christian peasants

of neighbouring Bosnia and Herzegovina against local Muslim

landlords, Serbian and Montenegrin agitation turned these

riots into nationalist movements. This was in 1853, in 1860-62

and again in 1875. In 1860 the Montenegrins actively supported

a rebellion in Bosnia-Herzegovina. When the Ottoman governor

of Bosnia suppressed the rebellion and then invaded

Montenegro, the powers intervened to save the autonomous

status of the small mountain principality. When the 1875

rebellion broke out, it set in motion a train of events that

nearly ended the Ottoman Empire’s presence in Europe.

The Tanzimat

There can be no doubt that the continuous external pressure

was an important incentive for the internal administrative and

legal reforms announced during the period of the Tanzimat

(1839-71). This is especially true for those reforms that had

to do with the position of the Christian minorities of the

empire. The European powers pressed for improvements in the

position of these communities, which in the classical Ottoman

structure had been that of second-class subjects. Slowly but

surely they achieved equality with the Muslim majority, at

least on paper. This, however, never induced them (or the

powers) to forgo the prerogatives they had under the older

millet system. The powers were certainly motivated in part by

the desire to extend their influence through the promotion of

client groups - Catholics and Uniates (members of the Eastern

churches who recognized the authority of the Pope) for the

French and the Austrians, Orthodox for the Russians, Druzes

and Protestants for the British - but genuine Christian

solidarity played a role, too. The Victorian age saw a marked

increase in piety and in the activity of missionary societies

and Christian fundamentalist movements. The missionaries were

increasingly active in the Ottoman Empire and they provided

their supporters at home with - often biased - information on

current affairs in the empire, so creating a great deal of

involvement on the part of public opinion.

It would be wrong, however, to attribute the reforms to

foreign pressure alone. Like the Gulhane edict of 1839, they

were used to gain foreign support or to avert foreign

intervention, but they were also the result of a genuine

belief that the only way to save the empire was to introduce

European-style reforms.

The post-1839 reforms covered the same areas as Mahmut IPs

programme: the army, the central bureaucracy, the provincial

administration,

6 ■ The Crisis of 1873-78 and its Aftermath

The Young Ottomans returned to Istanbul motivated by an

astonishingly naive belief that with the deaths of Fuat Pasha

(in 1869) and Ali Pasha (in 1871), the obstacles to democratic

reform would disappear. They soon found out that, quite to the

contrary, the death of Ali Pasha was the first stage in a

development that in the course of a few years would lead to a

crisis of unprecedented proportions in the empire.

A number of developments coincided to cause this crisis.

Internationally, the empire’s position had begun to change

even before Ali Pasha’s death. The opening of the Suez Canal

in 1869 meant that Egypt, rather than the empire, became the

focus of interest for the main liberal powers, France and

Britain. The clear and unexpected defeat of France by Prussia

in the war of 1870—71 meant a change in the balance of power

in Europe; France, the power most closely associated with the

Ottoman reformers since the Crimean War, was in temporary

eclipse. This in itself strengthened the hand of the partisans

of the authoritarian and conservative powers (most of all

Russia) in Istanbul. At the same time, the sultan, who had

already shown signs of impatience at the way Fuat and Ali kept

him out of the conduct of public affairs, used Ali’s death to

exercise power himself, something for which he was by now illsuited because of his increasingly idiosyncratic behaviour and

emerging megalomania. One way he tried to exercise control was

by not letting any official become entrenched in his post,

shuffling them around at a frantic pace. The sultan’s righthand man in 1871-72 and 1875—76 was Mahmut Nedim Pasha, who

went to extraordinary lengths in seeking the sultan’s favour

and who was so openly in the pay of the Russian embassy that

he earned himself the nickname ‘NedimofP.1 Nedim Pasha had no

experience of Europe nor did he know a European language and

was thus ill equipped to lead the empire in times of crisis.

Economic causes and political effects

The crisis that developed in the 1870s was economic as much as

it was

72

TURKEY: A MODERN HISTORY

(or became) political. A combination of drought and floods led

to a catastrophic famine in Anatolia in 1873 and 1874. This

caused , the killing-off of livestock and a depopulation of

the rural areas through death and migration to the towns.

Apart from human misery, the result was a fall in tax income,

which the government tried to compensate for by raising taxes

on the surviving population, thus contributing to its misery.

As had become its practice since the Crimean War, it also

looked to the European markets to provide it with loans, but

they were not forthcoming. A crash on the international stock

exchanges in 1873, which marked the beginning of the ‘Great

Depression’ in the European economy and which lasted until

1896,2 made it impossible for dubious debtors like the Ottoman

Empire to raise money. As a result, the empire could no longer

pay the interest on older loans and had to default on its

debt, which by now stood at £200 million.3

With the increased pressure of taxation, the unrest in the

empire’s Balkan provinces (which had not been affected by the

famine) escalated into a full-scale rebellion of the Christian

peasants, first in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and from April 1876

also in Bulgaria. When Ottoman troops suppressed the

rebellion, killing 12,000 to 15,000 Bulgarians,4 a shock wave

swept through Europe, which virtually ignored the large- scale

killings of Muslims by Christians that were also part of the

picture. Especially in England, where Gladstone’s Liberal

opposition used the ‘Bulgarian Massacres’ as propaganda

against the Conservative government of Disraeli (which was

accused of being pro-Turkish and thus an accessory to the

killings), the Turkophile atmosphere, which had prevailed

since before the Crimean War, disappeared.

Russia and Austria-Hungary had been involved in intensive

discussions on the ‘Eastern Question’ since late 1875. Austria

still regarded the survival of the Ottoman Empire as a vital

interest. Besides, its military authorities strongly advocated

the occupation of Bosnia- Herzegovina in case Ottoman control

there faltered. In Russia, on the other hand, pan-Slav

solidarity with the southern Slavs was now widespread and the

Russian ambassador in Istanbul, Ignatiev, was an ardent

supporter of the movement. The Russian—Austrian discussions

resulted in the ‘Andrassy note’ (called after the Austrian

Foreign Minister) of 30 December 1875. This was a set of

proposals for far- reaching reforms in Bosnia-Herzegovina

under foreign supervision. The Porte accepted it in February,

but the rebels refused to give up their fight. A short

armistice in April was soon breached.

The constitutional revolution

In this ominous political and financial chaos, a group of

leading

THE CRISIS OF 1873-78 AND ITS AFTERMATH 73

Ottoman politicians, including the provincial reformer Mithat

Pasha (now minister without portfolio), the Minister of War,

Htlseyin Avni Pasha, the director of the military academy,

Suleyman Pasha, and the §eyhiilislam Hayrullah Efendi, carried

out a coup d’etat, deposing Sultan Abdiilaziz on 30 May 1876.

In his place, Crown Prince Murat, who was close to the Young

Ottomans and who had been in touch with Mithat Pasha through

Namik Kemal and Ziya Pasha, came to the throne as Sultan Murat

V.

Before his accession, Murat had promised to promulgate a

constitution as soon as possible, and it seemed as if the

Young Ottoman programme (constitution and parliament) would

now be implemented in full. Namik Kemal and Ziya Pasha were

appointed as palace secretaries. Once on the throne, however,

Murat listened to Grand Vizier Ru§tu Pasha, who urged caution.

Instead of a concrete promise of a constitution, as advocated

by Mithat Pasha and the Young Ottomans, only a vague statement

on reforms was included in the Hatt-i Humayun (imperial

decree) after Murat’s accession.

On 5 June 1876 ex-Sultan Abdiilaziz committed suicide. Then,

on 15 June, a Circassian army captain called Hasan, motivated

by personal grievances, shot and killed Hiiseyin Avni Pasha,

Minister of Foreign Affairs Re§it Pasha and several others

during a cabinet meeting. This changed the balance of power in

favour of the more radical reformers. On 15 July the first

meeting of the new Grand Council decided to proclaim a

constitution. This could not be carried through, however,

because of the rapidly deteriorating mental state of Sultan

Murat.

Murat, who was by now an alcoholic, had shown signs of

extreme

nervousness when he was taken from the palace on the night of

30 May

to take the oath of allegiance from the high dignitaries of

state at the

Porte (he was convinced that he was being taken to his

execution).5 The

suicide of his uncle and the murder of several members of his

cabinet

seem to have led to a severe nervous breakdown. After having

the

sultan examined by Ottoman and foreign medical experts, the

cabinet

had to conclude that he was unfit to rule. It first tried to

get his younger

brother, Hamit Efendi, to act as regent, but when he refused

had no

choice but to depose Murat and replace him with Hamit, who

ascended

the throne as Abdtilhamit II on 1 September 1876. Murat was

taken to

the Ciragan palace on the Bosphorus, where he lived in

captivity for nearly 30 years.

The Bulgarian crisis escalates: war with Russia Meanwhile tile

situation in the Balkans had gone &om bad to worse m had

declared war on the empire on 30 June 1876 but, faced with

74

TURKEY: A MODERN HISTORY

the superior strength of the Ottoman army, it had to sue for

an armistice by September. By this time, however, pan-Slav

feeling in Russia had reached a fever pitch. Disappointed in

Serbia, the Russian pan-Slavists now concentrated on the

Bulgarians and the Russian government put pressure on Istanbul

to introduce wide-ranging reforms and virtual autonomy in the

areas inhabited by Bulgarians, threatening war if its demands

were not met. Britain now tried to defuse the growing crisis

by proposing an international conference on the Balkans. When

the conference met for the first time, in Istanbul on 23

December 1876, the delegates were startled by the Ottoman

delegate’s announcement that a constitution had now been

promulgated. It was based primarily on the Belgian

constitution of 1831, but a number of its articles (or

omissions) gave it a more authoritarian character and left the

sultan important prerogatives, which he was later to use to

the detriment of the constitutional government. The

authoritarian traits of the constitution were modelled after

the Prussian constitution of 1850.

The promulgation of the constitution, from the Ottoman

standpoint, made all discussions of reforms in the Christian

areas of the empire superfluous, since all subjects were now

granted constitutional rights. The Porte rejected all further

proposals by the powers. As a result the conference failed and

on 24 April 1877 Russia declared war, having first bought

Austria’s neutrality by agreeing to its occupation of Bosnia

and Herzegovina. At first the Russian armies met little

resistance, but then they were unexpectedly checked at Plevna

in Bulgaria, where the Ottomans withstood a number of Russian

assaults from May until December.

When the Russians finally broke through it meant the end of

effective Ottoman resistance and, by the end of February, the

Russians were at San Stefano (modem Ye§ilkoy), only 12

kilometres outside Istanbul. On 3 March 1878 a peace treaty

was signed there, which was an unmitigated disaster for the

Ottomans. It included the creation of a large autonomous

Bulgarian state between the Aegean and the Black Sea, enormous

territorial gains for Montenegro (which became three times its

prewar size) and smaller ones for Serbia. Serbia, Montenegro

and Romania became independent. Far-reaching reforms were to

be carried through in Thessalia and Epirus. In Asia, Batum,

Kars, Ardahan and Dogubeyazit were ceded to Russia and reforms

were to be introduced in Armenia. Furthermore, the new

Bulgarian state was to remain under Russian occupation for two

years. Obviously, it remained under Russian influence even

after that period.

The signing of the treaty produced the shock effect needed

to prod the other European powers, notably Austria and

Britain, into action, not

THE CRISIS OF 1873-78 AND ITS AFTERMATH

75

because of any sympathy for the Ottomans, but because Russian

domination of the Balkans and Asia Minor was unacceptable if

the European balance of power was to remain in force. Pressure

and sabre-rattling on the part of Austria and Britain led to

the holding of a conference in Berlin in June 1878, to find an

acceptable solution to the ‘Eastern crisis’ as the ‘Eastern

Question’ had now become. It was to be the last in the series

of great conferences attended by all the major European

powers, which had started in Vienna in 1814. Needless to say,

the influence of the Balkan peoples and governments at the

conference was negligible.

The end result of the conference, the Treaty of Berlin,

mitigated, but did not nullify, the provisions of San Stefano.

Romania, Serbia and Montenegro still gained their

independence, but the territorial gains of the latter two were

much reduced. An autonomous Bulgaria was created, but it was

much smaller than originally envisaged and it was split in two

along the Balkan mountain ridge, the southern part remaining

an Ottoman province under a special regime with a Christian

governor. In Asia, most of Russia’s acquisitions, including

the port of Batum, remained in place. Moreover, both Austria

and Britain had exacted a price for their intervention Austria now occupied Bosnia- Herzegovina (which technically

remained part of the Ottoman Empire) and Britain did the same

with Cyprus. The sultan had no choice but to acquiesce.

2

The Tanzimat

CARTEL VAUGHN FINDLEY

In Ottoman history, the term 'Vanzimat i literally 'the

reforms'j designates a period that began in 1839 and ended by

Literary scholars speak of'Tanzimat literature' produced long

after arguing thar the literatim: displays continuities that

warrant such usage. Reform policy also display* continuities

after 1876. Vet the answer to the critical question of 'who

governs’ changed. The death of the Ism dominant Tan&imaJ

statesman, Mehmed Cmin Ali Pa$a (1871), and the accession of

the last dominant Ottoman sultan. AbdtHhamid II (1876).

decisively changed the answer to that question.

Background

No disagreement surrounds the beginning of the Tanzimat, f<«*

several watershed events occurred in 1-839, including a change

in who governed’.1 However, Ottoman efforts at modernising

reform had begun much earlier, The catastrophes that alerted

Ottomans nr) the menace of European imperialism began with the

Russo-Ottom.an War of iy^-74, ending with the disastrous

Treaty of Kti^iik Kaynarca. That treaty launched the series

o/criscs known to Europeans as the 'Eastern Question’, over

how to dispose of the lands under* Ottoman rule. Napoleon's

invasion of Egypt <1798) was equally traumatic, although

temporary in its effects compared to Kii<;Uk Kaynarca. as it

showed that the imperialist threat wm not localised in the

European borderlands but could make itself felt anywhere.

These crises stimulated demands in both Istanbul and the

provinces ■ ibr example at Mosul ibr an end to the political

decentralisation of the preceding two centuries and a re

assertion of sultamc authority*

1 This chapter is. adapted from Carter Vaughn

‘Turkey.

KUni, N4fkwwli<r», and

Modernity', ch. a {forthcoming! i Dina Rkk Khtwry, $UU* <ttut

I'mrofW $<vie?y f<? the Otlowtan Empire;

> f S;.j

(Cambridge: Cambridge Unm-tsny Press, wv'u =60 78, pp

11

CARTER VAUGHN PINOtB*

Sultans Setim HI (1789-1807) and Mahmud U (J#Q8~>9) responded

with reform programmes that opened the Ottoman reform era

(1789-192,2).

Seliro's 'New Order' (Nizanvi Cedid) aimed first at military

reform. As in other stales, military reform required more

revenue, and more revenue required more efficient government

overall. Pacing that fact, Ottoman statesmen came to realise

rhar a governmental system previously guided by custom had to

be reconsidered as the object of rational planning and

systemarisa* tion. Lacking precedents to follow, rhe resulting

new programmes required plans, regulations and laws ro guide

them. There would be no Nizam-i Cedid without

(regulations, literally writings about order). The

plans

and regulations that defined Sclims New Order mark the point

at which the Enlightenment s svstematising spirit (esprit de

syslctne) appeared in Ottoman policy; Selim's decision to

inaugurate permanent diplomatic representation in Europe

(1793) furthered this rapprochement between Ottoman and

European modes of thought. In Weberian terms, the perception

that the New Order required planning and regulation marks the

beginnings of the transition from 'traditional' towards

rational legal' authority. In Ottoman terms, finally it was

the sultans command that gave the new regulations the force of

law. The warlords who had wielded power by default during the

period of decentralisation could nos wield power by right. The

sukan could do so, if he possessed sufficient strength of

will, and the re assert ion of his right meant centralisation

and an end to warlordism.

In attempting to create new institutions while unable to

abolish old ones, Selim II f left himself open to attack by

vested interests threatened by his reforms. Jits overthrow

i^esuired from this fact. To avoid repeating Selims mistake,

Mahmud II prepared carefully. Me neutralised provincial

warlords where he could, although the biggest of them, Egypt’s

Mehmed Ali, eluded him. By iBz6 Mahmud was strong enough to

abolish the Janissaries, the once- famou* infantry corps that

had become undisciplined and ineffective to the point of being

a Habiliry: The fact that Sultan Mahmud's forces performed

poorly against the Greek revolutionaries, while Mehmed Ali

Pa$a‘s Egyptian troops performed well, heightened the sense of

urgency in Istanbul. The aho Hi tion of the Janissaries, the

most dangerous vested interest opposing reform, made it

possible for Mahmud to revive Selim’s programme and go beyond

it.* Beginning with a new array and reorganised support corps,

Mahmud went on

5 AvSgdor Levy, "Th« Military Policy of Sultan Mahmud 11’

{Ph.D. thesis. Harvard University, pp. tot- »4

i%

The Tanziirmi

to found new schools, revive diplomatic representation, and

rationalise civil and military institutions overall

Ottoman statesmen under Selim and Mahmud realised that the

empire could no longer defend its interests militarily without

external aid, This realisation raised the importance of

diplomacy and cemented the tie between defensive modernisation

and reforms intended to appeal to European interests. Two

measures from Mahmud’s last years prove the extent ofhis

attempts to align Ottoman and European practice. Dependent on

British support in the last phase of his conflict with Egypt's

Mehmed Ali Pa$a, Mahmud concluded the Ottoman-British

commercial treaty of 1838, which essentially introduced free

trade. The I maty has often been interpreted as ruining

Ottoman manufactures. In fact, the Ottomans' dependent

integration into the world economy had already begun. Both

Ottoman and British negotiators understood the treaty as an

agreement aimed against the interests of Mehmed Ali, a rebel

but still an Ottoman subject and thus bound by the treaty. If

Liberal ideas were introduced in economics, they would have to

be introduced in politics as well. The Gulhane decree 0/1859,

promulgated after Mahmud's death but prepared before it, took

that step. The decree is usually understood as inaugurating

equality among ail the sultan's subjects, whether Muslim or

non-Muslim, bur that interpretation is not entirely accurate

or complete.

What was the Tanzimat?

Between Mahmud's death (18391 and Abdulhamid’s accession

{187^, no sultan dominated policy consistently, Selim and

Mahmud's new elites filled the gap. Because defence depended

011 diplomacy, it was nor the military bur rather the civil

elite, especially the diplomats, who became most influential

The centre of power shifted from the paiacc to the civil

bureaucratic headquarters at the Sublime Porte (Bab-i Ali).

During the Tanzimat, it became common for the foreign minister

to go on to serve as grand vex jr. Dominating this combination

of posts. Mustafa Re$td (j*oo~$8), Rc^ecizade Fuad (1815-69)

and Mehmed Emin Ali Pa?as (1815-71) shaped the period. Their

associates formed a revolving imerministerial elite, rotating

among ministries and provincial governorships.

Tanzimat policy represents « continuation and intensification

of reform. Both the name Tanzimat and the term nismn ('order")

had entered Turkish as loanwords from Arabic: and bolh terms

derive from the same Arabic root, which denotes ‘ordering' A

causative or intensive form of this root, Tanzimat implies the

expansion or intensification of ordering or reform, and that

was

ti

CARYHR VAUGHN FfNOLgV

exactly what happened during the Tanzimat. Ottoman policies

during chat period responded to emerging global modernity in

both its Janus-like faces, the threatening aspect (separatist

nationalism in the Balkans, imperialism in Asia and Africa)

and the attractive aspect (die hope of overcoming Ottoman

backwardness by emulating European progress). The Tanzimat was

both a rime of crises, which implied impending collapse, and

of accelerating reforms, which signified renewal.

As greatly as government policy defined this period, the

formation of new elites and the propagation of new ideas also

slipped beyond government control. Here the most significant

factor was the rise of the modern print media. As government

policy moved further into realms not sanctioned by custom,

critics found more to contest. Consequently, the rise of the

print media was soon followed by that of a.modern opposition

intelligentsia, which used the media to appeal to the emergent

reading public. Less conspicuously, a conservative current,

appealing to propertied interests and grouped most noticeably

around reformist religious movements, was also taking shape,

'{lie conservative trend gained momentum, particularly with

the emergence from Ottoman Iraq of the KhalidiyyaNaqshbandiyya. founded by S’haykh Khaiid al-Naqshbandi (17771826), known as the 'renewer‘ (mujaddiet) of his century The

remainder of this chapter examines the Tanzimat more fully.

Crisis and contraction

The period began and ended with the empire’s survival more

threatened than at any other time in the nineteenth century.

When Mahmud II died in 1&39, he and Mehmed Ali were at war The

latter controlled Crete and Syria as well as Egypt, and had

just defeated che Ottoman army inside Anatolia; die Ottoman

fleet had also defected to Egypt, ’fhe European powers found

the imminent prospect of Ottoman collapse so destabilising

that they intervened in Istanbul's favour. Mehmed Ali was

pushed back, left as hereditary governor of Egypt, and

deprived of his other territorial Egypt j-emained under

nominal Ottoman sovereignty until X914. Under MehmedA&'f

successors, Egypt became increas- ingly both autonomous from

Istanbul and economically dependent on Rurope. Both cotton

exports and the Suez Canal (1869) increased European

investment and strategic interest in the country, setting the

course that led die British to occupy Egypt in i#Hz.

Following the Egyptian crisis of r840-t, the Ottoman Empire

endured a series of local crises that expressed the growing

politicisation of religious and ethnic differences among its

subject populations. Crete and Lebanon sankinto

M

The Taiwtmji:

crises of this type follow nu. iIm t reversion from. Egyptian

to Ottoman rule. Cretan Christians wanted wm>h with

independent Greece, ami the islands historical Chrisd;m-Mtnimi

vj mnosis dissipated into viokn.ce, leading to the revolt

ot'1866. In Lebanon, the okl net work of relationships that

bridged differences of religion and class Had alre ady been

destabilised under f.lgy pcian rule in the 3830s. These

relationships collapsed totally under restored Ottoman ruk

from the impact of both the Tanzimat reforms and the

increased, penetration by Europeans especially missionaries,

who cxtmA new religious differences and politicised old ones.

Sectarian contacts broke out in Lebanon in the 1840s, followed

hy rfms-bzsed conflict?. Damascus lapsed into sect&naiJ

violence in the i$&os. Hie Lebanese crisis led the Ottomans,

in agreement with major European powers, to introduce special

regulations, under which Mount Lebanon would have a special

administrative system, headed by a non* Lebane.se Christian

governor, This? system brought security at the pricct of

lastingly imprinting the new sectarianism on Lebanese

politics.'1 In Damascus, the Ottomans banished the old elites

who had failed, ro restrain the violence of i&ftn thus

fedUtating the rise of a new local elite with interests in

landholding and office-holding.'

In die Balkans, after Serbia won autonomy -1815) and Greece

won independence ifS.io). separatist nationalism continued to

p * <d ufgam flourished economically under Ottoman rule,

despite exp*raring twelve minor insurrections between 1835

find i.Hyti6 At first, the mo »t £.ii«vn? Balkan issue

concerned the Romanian principalities of WaBachia and Mold

rvia. Desiring unification, Romania became the only part of

the Ottoman fcmpine to get caught up m the European

?*vo!urionary wave ofr$4#. Romanian nadsmalism was repressed

then, but unification (t8rt? * and independence (tR?#* were

only questions of time. Alter 1848, the Ottomans also gave

asylum to both Polish and f luntgarian revolutionaries of

184$, whose contribution to Ottoman defence and culture proved

sigysifkant, despite the resulting tensions in relations with

Russia and Austria."

4 Ussama^fakdlsi.

s *\ »i> i 1Hwon f (V >i ) «'* (tenth

WsaHe’M’Berk«ieyaiidl.u A <•»«!< I niversir f htnii

won):

BrtgittAkadi/IlifU'iigPiWf.iXbi.-itjznfhe.H' v a ) i

losAjigcfox * >tw r i \ i< <itforai<? Press, 5«»);j.CH!ir it

lUtP f i in > ?r h tn at {ranti 1 o tcntaryr Record (New Haven

liw t in k i i

( [ f *44-«5 Philipp. Khoury. Utl « 4 abt t i \i M l! tih n h

hhticsajftetiMMwx, fts'j-tzsa ^Cambridge; C<*mla ^ C is u in

* 1

6 Michael PalaireE. Tic r* U T 1 m > 4 I Mien mthw Dtwhpmeni

(Cs»Tnbtit$gc: Czmi sdt i m u !u s f-\ ** 3. &7 (Ilxi- Onsyis. Jmptti ?? j ^ t v ■* \ t I n U HI >tr'<p]>.

'4<\ *<«-•;*•

*•>

CAftTRft VAUGHN VMTilsgY

Balkan tensions did not produce a major war until i$y?, but

the same issues soon caused war over the Christian holy

places. The crisis grew out ofa dis- p\x\:t between Catholic

and Orthodox ttergy over the keys to the Church of the

Nativity in Bethlehem/ Such issues were not new, but the:

growing politi- dMtion of religious difference made them iesv

n anageable than in the past, as did the European powers*

competition to dump*on the interests of different religious,

cotnmuniti.es. Claiming protectorship of Orthodoxy, Russia

issued •an ultimatum. In return for Ottoman promises of

further egalitarian reforms, France and Brium declared war on

Russia. The war was fought in the Balkans and the Crimea and

became known as the Crimean War (i&b-*’)- further

acr.elcra.ting the Ottoman onrush into modernity, the war

brought with it the huge casualties caused by new weapons, the

improvements in medical care symbolised by Florence

Nightingale's pioneering efforts to provide nursing care for

the wounded and advanced commumcationx in the form of both pho

tograph and telegraph, which readied Istanbul during the war.

At the war’s end, the. sultan issued his promised reform

decree of *80, discussed below; and the Treaty of Paris

formally admitted the Ottoman Empire to the concert of Europe.

The Ottoman Empire thus became die first non-Western state co

conclude a treaty with the European powers on supposedly equal

terms.0 However, the treaty contained contradictory clauses,

disclaiming interference in Ottoman affairs in one, while

neutralising the Black Sea, internationalising control of the

Danube and introducing European controls in Romania and Serbia

in others. The Ottoman Empire did not lose territory in the

war, but its sovereignty was further breached.

The territorial loss averted in 1856' occurred in the t870s.

Revolt broke out in Herzegovina in &?4 and spread to Bosnia,

Montenegro and Bulgaria by 1876, The Ottoman government,

havingjust suspended payment on its foreign debt, had to face

this crisis without European support.16 Ottoman efforts to contain the simatkm raised European outcries against massacres of

Christians, even as counter-massacres in die Balkans began to

Hood Istanbul with Muslim refugees, whose plight Europeans

ignored. In Istanbul, the political situation destabilised to

the point that two sultans were deposed within three months,

and Abdlilhamid came to the throne as the third sultan to rule

in t$?6. At once

& Pawi Dumom, ‘D* p»iri«*Je tk*s Tanzimat’, in Robert Maulxan

Histtrir? 4e VBmpin.'

otKnnan (Pans: bayard, £$$91. pp. 505-09 Burewitx, Mithik ami Nerlh AJHau vol. i, pp. a.

so §cvke( Pamak, A Mmmary tti$u*ry <f tht Ottemm Empire

(Cambridge: Cambridge Itoiversiiy Press, zooa’u p. zif. Francois Georgf.on, Akiiilkamui

th Ic mluin atiifk (i$7§~i$z>9)

(Pads: V%yavd, 1003), pp. 7%- %.

f6

i

1

Tlw Tatwimas

a triumph of Ottoman reformism and. a bid to ward off European

interference, the Ottaman constitution was: adapted Deeember

?S7*s) and parliamentary elections were ordered/' No friend of

constitutions. Russia dedared war anyway, attacking in both

the Balkans and eastern Anatolia, The RussoTnrkish War (‘*8778} created, the crisis conditions that enabled Abdulhamid to

end both the bureaucratic hegemony of the Tansdmat and the

First Constitutional Period

The Russo-Turkish War brought the empire closer to

extinction than at any time since J839. Europeans who knew

nothing of the Tanzimat except the Eastern Question might have

found tt logical to dismits the empire as 'the sick man of

Europe', Only by looking srtside does it become possible; to

form a different view.

Major themes of reform

While reformist initiatives proliferated tn this period to a

degree that defies summary, they cohere around eertatn themes:

legislation: cduc&ikm and elite formation; expansion of

government; inrercommunal relations; and the transformation of

the political process. Late in the period, the reformist

momentum grew, producing systemausing measures of wide import,

fn 1&67. Sultan Abdtil.agiz became the first sultan to tour

Europe, with a large suite including foreign minister Fuad

Pa$a and Prince Abdiilhamid- This trip may have helped to

stimulate the far-reaching measures on provincial

administration, education and. the army that ensued between

5867 and 187 s.'2

Legislation

ifde facto dvil bureaucratic hegemony demarcated die Tanzimat.

chronologically, the main instrument of change was

legislation/5 In a sense, the Tmsimat. was fundamentally a

movement in legislation. In essays of the rB.ios, for example,

Sadxk Rifat Pasa< then serving as Ottoman ambassador in

Vienna, elaborated the connection between external and

internal public law, between secur- in.gthe empire's admission

into the European diplomatic system and maintain ing a just

internal order. European demands for internal reform in

exchange for international support in 1839 and 1854 made the

same point. Beginning

a Di.sm<inii T«wim;k', pp. Barbara jekvirh. History tkrHighuxnth *m<i

Ninrtttnth Centuries

Cambridge University Press. 19871,

,*u h%

w CevH-gcen, AMuikamUi U, pp. ;»~5. i.l Ovraylj,

imi'4mt#rhi$n.a> pp. t?p $o,

17

CARTER VAUCJH8 RNZH8T

with the Nizam-t Cedkf the connection between reform and the

drafting of instructions, regulations andlavsrs had t mpressed

itself on Ottoman statesmen's awareness. The fact that

instructions and laws took effect through die sultan's powers

of decree made centralisation, reform md legislation

interdependent. Whenever a given reform, required

implementation all over the empire, the necessity for dear

orders and regulations became especially obvious.

Although they were only crescs on an evef-gacheringwave of

regulation, the most important legal acts of the Tanzimat were

the Gulhane decree of 1839, the reform decree of and the

constitution of 2876. Opening the period, the GUlhane decree

proved less of a westernizing measure than has commonly been

assumed.w It called for reforms in taxation, military

recruitment and judicial procedure, and it extended guarantees

for life, honour and property to all subjects, Muslim and nonMuslim, It promised new laws to implement these reforms -■ a

promise from which a Hood, of new laws flowed. The decree

reflects British Liberal thinking in its denunciation of taxfarming and monopolies and in several specific guarantees. Yet

die repeated references to promulgating kawnin-i $cr'iyc, laws

conformable to Islamic law (jmat), to fulfil the decree's

promises also reflected the Ottoman tradition of aligning

state law (kmun. plural kavaniri) with theicria*. Although

commonly so interpreted, the decree did not say that Muslim

and non-Muslim are equal, which they are not under

%ht.j(eriat, The de ee drJ declare chat the privileges it

granted applied without exception to all s bje f :he

sultanate, both 'Muslims and members of other communities'

(em-i isiam ve miiel-i saire'). as the .state’s Jaw (fcansin)

could do. The provisions on taxation spoke of replacing old,

exorbitant taxes with 'an appropriate tax' Tbir vergO-vi

miinasih'), The intention was to consolidate and reduce taxes;

vergu was not a generic word ibr taxes, but the name of a

specific new tax. The provisions on due judicial process,

finally, had special significance for the ruling elites.

Historically bearing the legal status of slaves to the sultan,

they had been subject to his arbitrary punishment (siy&>ei) in

a way that ordinary subjects were not. The decree repudiated

such punishments. 'This provision gave the ml.i.ng elites a

vested interest in keeping the decree in force, thereby making

of the decree a milestone in the process by which *iyast.t

acquired irs modern meaning of ’politics'.

Although the Gulhane decree had not explicitly stated the

equality of non- Muslims with Muslims, the Reform decree

(fslahat fermam) of 1856 did/5 It

U Ahmtd LutB, Tarih-l Lh0 {K.«*nb«J: Muhmud Bey Mitbaaji,

vol. VI,

|>p, ^-5; Sun* KUi and A. §errf t.>#*Ub«5j?8k, Turk atutws*

matinlm, Smetii imjkkt/xn gwimiizc (Ankara: Turklye 1?

Banbts?, i$%>, pp. u-13.

Kiii -and GiSzabHyiik, Tiirk anay^m, pp. I4-j8.

j B

The Tanzimat

enumerated measures to be enacted fr»r ihe benefit ‘without

exception, of all my imperial subjects of every religion and

sect*. Reaffirming historical communal privilege*, the decree

invited non-Muslim* to form assemblies to reorganise their

aftasvs. As a result, non-Muslim communities drew up communal

regulations {nizamnamet, sometimes t ailed constitutions', and

formed representative bodies.!t' The decree libei alised the

conditions for building and repairing non-Muslim religious

buildings, fs thrbadc language or practices that held some

communities lower than others', it proclaimed Ottoman subjects

of all religions eligible for official appointment according

to their ability, and opened civil and military schools io

all. The decree extended the obligation of military service to

ncm-Mushtns hut allowed for exemption upon payment of a

substitution fee i bedel): buying exemption became the norm

for non-Muslims, and the fee replaced the azye. the tax that,

the $eriat required of non-Muslims. Court cases between

parties from different communities were co be heard before

mixed courts, although cases between coreligionists could

still be heard in communal courts.

The third fundamental act of the period, the constitution of

i#7<\ WAS a logical response both to the international

situation and to the organic regulatory acts promulgated for

various parts of Ottoman polity. In the os, in addition to

those of the non-Muslim communities, organic statures had

defined special regimes for Lebanon and Crete; at die Ottoman

peripheries, Tunisia had its constitution for a rime in the

r8<*os. and Romania acquired one in 1M6. With growing Ottoman

awareness of European practice, organic regulation of parts of

the imperial system heightened demands for a comtitunors for

the whole.17

Hastily drawn up by a commission including ulema, military

officers and civil officials, the constitution contained

compromises and imprecisions. Yet it showed the extent ro

which ideals such .is rule of law, guaranteed rights and

equality had permeated Ottoman thinking. The articles were

grouped in sections pertaining to the empires territorial

integrity, the sultanate: the subjects' rights and

obligations, the ministers; the officials; the parliament; the

courts; the provinces; and a final miscellany The articles

included provisions pregnant with future consequences. Article

7 left the sultan's prerogatives undefined, although it

mentioned many of them; these included appointing

rtf Dumont, Tanxfnt^t . pp, ..»«>?-vx*.

rt Rottelic U. Davbton, Rrfinm in t(uf On^m» Empire,

fPrmmotv l-lmto.,£.nu

University Press, tp6i\ pp. 04- !.%

Nismv •>/' the t.v,

pp. /05 w. Otter

Vaughn

ftcjortn m the Ouom,(n fimpiK; Th? Sablim? fWh’. t

r U2

iPrit’ceron: Princeton University Press, i <*&>:. pp

CABTBR VAUOMK PINOLE*

and dismissing ministers, who would consequently have no

collective responsibility.

Eiifoixremcntoffcrfatasid^anunformcdpartofthe imperial

prerogative. The constitution itself became law only by

imperial decree; the sultans right to continue legislatingby

decree was nowhere restricted; and his freedom to veto laws

passed in parliament, where the ministers retained most of the

legislative initiative, was unchecked. Article 113, inserted

at Abdulhamid's insistence, acknowledged the sultans right

under martial law to exile anyone on the basis of a police

report identifying that person as a security risk.'* Although

martial law was not in force at the time, constitutionalist

hero Midhat Pa$a went into exile in 1876 as a victim of this

provision.

If the acts of 1839,1856, and t«76 formed the crests on die

wave of legista tirnt, much of the wave’s mass consisted of

new codes. An initial penal code (18401 was revised (.1851)

and replaced wkh a code of French origin (1858). Also French

inspired were the codes of commerce (£850, j86;j). When Ali

Pasa proposed adapting the French civil code as well, the

ulema resisted, (nscead, a codification of $«rtot law was

undertaken under Ahmed Cevdet Papa's direction and published

as the Mecrtle (1870-7). Also significant was the land law

(arazi kanunmmcsi) of *858. which codified and systemarised

die historical Ottoman principles of state ownership over

agricultural lands (miri). The law attempted to protect small

cultivators (successfully or not, depending on local

conditions), clarify titles and identify the responsible

taxpayers/9 Thousands more laws and regulations affected life

in coumless ways, adapting Ottoman to international practice

in many cases, for example by prohibiting the slave trade.**

New courts were created to apply the codes, starting with

commercial courts (1840), presided over by panels of judges

named by the government. By the t86os, a network of nizatni

courts had evolved to try cases under the new codes. As m the

case of the regular (nizarni) army, the adjective (deriving

from wtoxm, ’order’) identifies the new institutions as

productsofdie mforms. The aisami courts were organised

hierarchically, with two levels of

i«*i Robert Devereiut, Ttie First Ottoman Constitutional

Period: A Study of the Mutiuit Cmshlv- turn arui Parliament

(Bitkiimo’e; JoJjjjs J lopkias Press. pp. 60 -79; Davawn,

lkj£*m, jyp, 158 -408; Gcftrgcmn Ab*iiiflmmid II. pp. 68-71.

19 Donald Qvwuert, ‘The Age of Reforms. 1X11-17x4. m

HaUlfoalok.aruJ DnnaUQuauert iciis,}. An Sivmmk ami Social

History (ifthe OtumanBmiritt, 1 4 (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1994), pp- ^5^‘6K Ortayh, hnpamtorbtgun, p

137; Muss Cadara, Titnwnat Mmwindt Hmtdoitf .wyai w yaptkn

(Ankara' I'Ckk T»i1h Kururou, «#»). p. *8.4.

20 Hhud R. Tokrdano, The Qttomart 5li»vc Trade anil iis

Supptrsshm, 1640-15<jo (Primxtwu Princeton University Press,

20

The Jjivim.tf

appeal courts above the courts of first instance; in contrast,

the jcrint courts tacked a formal appeals instance.

Many scholars have seen in the new codes and in the nizumi

courts many steps towards secularisation and breaches in the

role of Islam in the Ottoman state. Yet this assessment

overstates one issue and ignores another. In 1876,

AhdOlhamid's decree of promulgation still echoed the CJtilhane

decree’s reference to laws conformable to rhe sharia’ by

affirming the constitution's conformity to the provisions of

the jenVu {ahkam-i jcr'-i jem/}li The Mecdht formed the

clearest example of a major component of the new body of Uw

derived from the jerfctt. The land law of 185$ analogously

provided the clearest case where traditional Ottoman kmun

provided the. source for new legists* tion, The fact that

ulema continued to serve in the new courts, as in the new

schools, moderated what might other wise have, been

secularising reforms. However, as the empire gradually created

the outlines ofa modern, law-bound polity, which Turkish

legists idealise as a ‘law state' (hukuk dtvteti. compare the

German ideal of the Ra;htsshiat\. .mother problem persisted.

This consisted of the chasm between the ideal of a law state*

and rhe authoritarianism that either deified the law without

regard ?.o its human consequences, or else used law and

regulation instrumentaily to extend the reach ofa power that

placed itself above the !aw.u

Elite formation and education The need for new elites can be

gauged from rhe fact that the Ottomans created an enure new

army after abolishing the Janissaries. The civil bureaucracy

grew almost as dramatically, from roughly x000 scribes in

service as of 1770-90 to the 55.000-70,000 civil officials

serving at a time under Abduihamid. The Ottoman Rmpire was

still lightly administered compared to other states; yet this

was rapid growth.*3

With growth, disparities appeared in the extent to which

different branches of service benefited from reform, and these

differences aggravated inter-service rivalries. The elite

formation efforts primarily benefited military officers and

civil officials. However, even in those ser vices, gaps opened

between groups

xx Kill and G^Kfihuylik. 'Inrfc atutvasa, pp. JAt fa

zz Orfayfr. /mjttmr.trlugim, |ip. 7^-80; Findley. Bmravctatic

Refrrm, pp t(t\-5; Camr Vaughn PuuSey. ’Osironh xiyas^

du$utxe:vUi<J<r dcvtct ve hukuk: iusatt Haitian nu. huk.uk

d^vkts m%?‘ XH. [QnikwcO 7»»Jr T/mh Kcngrzxi, BiMiritcr f

Ankara; Turk Tsrth Kurumu, jnyaa), pp. rtpj-tzox

^3 Ftrsdtay Buresutr.uu K^lttwj, pp. :n~3, ara-tS

25

CARTfcK VAUfiHS 3PINI>i.8Y

with Afferent qualifications. Civil officials differed in

their degree of western isation, mastery of French serving as

the distinguishing trait. Military officers differed in being

cither 'school men' (mektepli), trained in the new academics,

or 'regimentals' (tdayh), who rose through the ranks and were

often illit erate.5 ? These differences created significant

tensions. Compared to the civil and military elites, the

religious establishment lost influence. The ulema still

carried weight as guardians of Islamic values, as masters of

the old religious courts and schools, as pan of the personnel

for the analogous new state institutions, and as an interest

group. Yet the reforms ended their historical dominance of

justice and education and their control of the revenues from

charitable foundations (cvkaj). Here as throughout the Islamic

world, the largest challenge to the ulema was that the

intellectual impact of modernity was transforming Islam from

the all-embracing cultural reality into one realm in the

universe of knowledge.-*

Tanzimat educational policy was largely driven by goals of

elite formation but gradually produced wider results. The

ulema's educational vested interests made the elementary

mcktchs (Quranic primary schools) and the medrcscs (higher

religious schools) virtually untouchable. The architects of

the new state, schools reacted to this situation by caking a

top-down approach to elite formation. They founded ostensible

institutions of higher learning first and added broader

outlines of a general system of schools later, with the consequence that many years passed before the new elite schools

could perform up to level. Military engineering schools were

founded early for the navy (177:0 and the army '179.I;. Mahmud

II created the military Medical School (1827) and the Military

Academy (1834), Students were sem to Europe, and an Ottoman

school briefly existed in Paris (1857Systematic efforts to

train civil officials began with the founding of the

Translation Office (Ten-time odasi) of the vSubltme Porte in

18*1; it was to train Muslims to replace the Greek translators

whom the Ottomans had employed until the Greek Revolution.

With time, founding schools to train elites became part of a

larger effort to create a network of government schools. The

first new schools for civil officials became the foundations

of the rujtltyc schools (1839), which were upper elementary

schools, intended to pick up where the Quranic mckteb left off

and educate students to about the age of fourteen. Middle

schools fidtaftye) began to be founded in 1845. initially to

prepare students for the military academy.

24 Omyii, hnfxutUorihguv, pp. 9>-iaa, 145 -5,1; Dumont.

T*a*aniat', pp. 47&#i *5 Cf. Adeeb KlvtBti, ThtPdtt&s of

Muslim Cultural R<form:JaiMtm w Centra! Asia ^Berkeley and

Laos Angeles; University of California Press, 19^8), ji 10a.

zz

The I

The first iyece isnltaniye) opened in 1H6X The most important

effort, to systematise education was the public eJuutian

regulations of i86tt (m.wrif-1 ttmumiyt New teaching methods

iuml-i calid). intended to

achieve literacy more quickly than in the mektebs, were

introduced ,is earlv as 1R47 and came into genera) use around

t«70. eventually spreading into Central Asia, There, these

methods assumed such importance in the development of cultural

modernism that the Central Asian m< idernists became known as

jddid- chilar('ne.w4$t$') because they championed this new

method' pedagogy.'8* For die Ottomans, several of rhe. new

school* became paiticulariy important m training civil

officials, notably, the Galausaray Lycce and the 5ch<x4 of

Civil Administration (Millkiye Mektebi, founded in 1859,

upgraded in f876>. Educating far more than the dices, the new

schools propagated lireracy and stimulated transformations in

individual self-consciousness and bourgeois class formation

among Ottoman Muslims by the 1870s" The schools' importance

for elite formation also included one unintended consequence.

For if Ottoman sulrans sought to cram new elites to serve them

personally, the ideas these men discovered at school led them

to transfer their loyalty from the sultan to their own ideal

of rhe state, a fact with consequences enduring to the

present.2*

G avert! m a t tal trxpans ion rrht> role of govern mem

expanded vastly during ihe Tanziraai. In Istanbul. the

expansion was physically obvious. Moving ro rhe new, oversized

Dolmahahcre palace, rhe imperial, household had its own

secretariat (tmbcyn) to communicate with the rest of the

government The civil, military and religious services had

their respective headquarters ar the Sublime J*orte i8ab-i

4Ih, Ministry of War (Bah-i Semskm), and the office of the

^yhiiltsfdm (fiab-i Ms.fihat). By 1871, the Sublime Porte

included the offices of rhe grand vezir and the council of

ministers, the foreign and interior ministries, and the most

impratam condliar bodies. Outside the Sublime Porte the civil

bureaucracy sho staffed the ministries of finance, charitable

foundations (evkafi. education, trade and agriculture,

customs, and land registry.**

26 Ibid , pp.

x? Setguk Akjirt Somd. 'Pbc Metktntxati.*»

t.iufdtkm in

thcOtu*md» Hmprr.

f*£: Islamimttm, M^mcy ami tteapliw il.ni&tn-. BriU, iooiV.

Carter Vaughn Rndtey.

Ottoman Civil Offkiakiftm: A Socud Winery (Pdmcum Princeton

University Press ry%i!>

PP- MX- 71catma MCige Gt>eck, Riif of Empire: Oticnxm Wr.<hr>ti?<ifieu

anA

SenaI Chang? (Nv,\v V>>rk: Otfcmi Univertftv m6>, 4-5-6.

n Findley, BunammUc ft&rm, pp. ufr <*0: Co$fewn Cakir,

Tanzimat J&mmt Ottmnh •n.ifcww*

Osranhui: KOcp. 100O. pp. #•••;>*: CaJiro. fdnzvtun

dtitwmiiuic Anadolu, pp

CARTER VAUGHN KINBT.RY

Along with the expansion of formal bureaucratic

organisations, an unprecedented proliferation of councils

(medis) occurred. These are often interpreted as steps towards

the creation of representative government. In the provincial

administrative councils, the inclusion of clected members and

local religious leaders supports that interpretation. However,

comparison with other administrative systems a bo shows

another dynamic at work. Historically, boards or councils

served as ways either to expand the reach of -an inadequately

staffed bureaucracy or to meet needs for which there was not

yet a permanent agency. In fact, the Ottoman Council on Trade

and Agriculture (1838) evolved into a ministry (1871), ami the

Council of Judicial Ordinances evolved into the Ministry of

Justice soon after, among many other examples.

With its expansion, government intruded increasingly into

Ottomans' lives. For example, each stage in egalitarian reform

produced effects; throughout Ottoman society. The local

councils brought together officials and local representatives

to implement policies about which they often disagreed.

Taxation and financial administration were repeatedly

reformed. Censuses and surveys of households and income

sources were carried out, Istanbulites were exempt from both

conscription and taxation; consequently provincials bore the

tax burden, and provincial Muslim males bore that of military

service. The regulations of 1869 defined their military

obligation as four years of active duty, six years of reserve

service and eight years in the home guard. At that time, about

*10,000 men served m the regular {nizami) army, 190,000 in the

reserves iredifi and 400,000 in the home guard (mustahfizan).

The 1843 division of the empire into five military zones with

an army based in each had created new sites of interaction

between the populace and the military. New schools created

puzzling new educational choices. New courts appeared, and new

laws affected matters as pervasively important as land tenure.

Mailing letters (1840), sending telegrams (1855), and

travelling by steamship (about 1830) ail became possible,

largely by government initiative. M ajor cities acquired such

innovations as gas street lights, regulations on construction,

new firefighting apparatus and the beginnings of public

transport. Modern government began to acquire monumental form

with the building of new provincial government headquarters,

schools, rousts, police stations and docks.w

40 (padun, 'iiitiznneu daru'mwdi Amuiclit. pp. 254-^13.3607.1; ^akix, Tanziimu tlmetni Osmunh maUyesi. pp, Z4--33;

Ortayh, fiMjwratorfutJua, pp. jry-ja; Dumont, Tanaaroit', pp.

Stanford j. Shaw arid Bzai K. Shaw. Hist&y of the Qtijmtm

Umpire smt M«4er* Turkov, vol. H: Rfrfbrm, Rrvoiutim, «m«i

iUpublic; 7'Ke hist ofMotlem Turkey, itot-ivj; (Cambridge'

Cambridge Uniueroiy Press. ivt75. pp. 91-5.

24

The Tanzimat

Provincial administration The changes in Istanbul affected

the provinces profoundly. For much of the period, reforms were

introduced into the provinces gradually, either as pilot

projects or as solutions to local crises, as in Lebanon- Not

uadi 1864 were provincial administration regulations

i'v(j<?y<rt wzrtmwtmwt) issued for general application.

Despite this gradualism, local administrative reiorm produced

significant impacts throughout the period.

Under the Gulhane decree, the first goal in the provinces

was 10 eliminate tax Winning 1Altiza.n1) and appoint salaried

agents (mwhoiiil) to collect raxes directly. The new

collectors' roles were more extensive than rheir tide implied.

‘Hiey were supposed to explain the Tanzimat and the equality

of all subjects, set up councils, collect faxes, and register

taxpayers and their property. The councils were to bring

together officials with representatives of the local populace

to discuss tax apportionment and other issues, live collectors

were expected to raise what they could from the populace and

forward it to Istanbul to finance the reforms. In the long

run. replacing many old exactions with the consolidated tax

(vcygu) announced at Cuihane would produce a significant tax

cut for tax-payers. The local administrative council (mcclis i

idare.} was to include the collector and his assistants, the

local religious leaders and four to svx elected members,

inspection missions were also sent out along three routes into

the Ottoman Balkan* and four routes into Anatolia in *840. As

of 1841, fifty were serving in ten provinces extending from

central Anato

lia to Bulgaria, Macedonia and the Aegean islands’1 However,

direct revenue collection was abandoned as early as 1843.. the

costs of replacing tax-farmers with salaried collectors

exceeded the revenues collected in many places. The. mdirect

electoral system made it easy for notables who had oppressed

the peasants in the past to gain election 10 the new councils.

Orthodox leaders reported to the Patriarch in Istanbul that

that they were ignored or scorned in the councils, and he

complained to the .Sublime Porte. Tax revolts occurred ui a

number of places. Tax-farming made a comeback, with some

exceptions, surviving as Jong as the empire lasted.

Yet elements of the programme survived. Local councils

endured and multiplied. Needed to assess the consolidated tax.

the. surveys of households and income sources, launched in

1840. were revised and implemented in 1S45 on such a scale

that over (7,000 registers survive. Replacing many old

extraordinary fprfi) taxes, but not the jrmit mandated taxes

like the tithe (d$wj and the

u ^'ak,*!v 'VmzmM Mncm Osmmh wftwi, pp. .1? ?, eoj 30, 3/I5300;

Tanzmat

iimemmdt An&tetn. pp. ao$-i8

*3

CARTBft VAUGHN fINDl.8*

tax on non-Muslims (cizyc), the consolidated tax (vrj^tf)

survived. For some years longer, this tax was not fanned out

but was collected at rhe quarter or village level by the

headman (muhtar) and the imam or priest. Dissatisfaction with

the new tax Jed to a project in 1S60 to systematise taxation

of real property and income on a proportional basis. However,

this endeavour required yet another survey arid was

consequently implemented only in places where chat survey

could be carried out/*

After the abolition of the new tax collectors (muhasstl) in

i%4Z, the provincial administration system began to assume the

outlines that would be systema- tised in the regulations of

1864-71 hi 1842,. the government revised the hierarchy of

administrative districts in regions where the Tanzimat had

been introduced, and started to appoint civil officials to

serve as chief administrative officers at three levels'

province (eyafcr), district (saiurak), and sub-district

(kaza)** These officials had supporting staffe and. at least