FEDERAL INCOME TAX OUTLINE I. STATUTORY INTERPRETATION

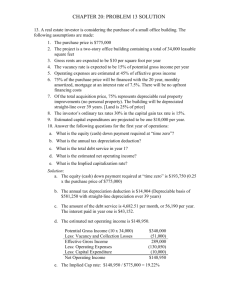

advertisement