The Effect of Risk-Based Capital Formulae on South African Medical Scheme Solvency

advertisement

Centre for Actuarial Research

(CARe)

A Research Unit of the University of Cape Town

The Effect of Risk-Based Capital

Formulae on South African

Medical Scheme Solvency

CARe Discussion Paper

prepared for the Council for Medical Schemes

by John Kendal, supervised and edited by Heather McLeod

May 2004

Centre for Actuarial Research

University of Cape Town

Private Bag

Rondebosch

7701 SOUTH AFRICA

Telephone: +27 (21) 650-2475

Telephone for Professor McLeod : +27 (28) 572-1933

Fax: +27 (21) 689-7580

E-mail: care@commerce.uct.ac.za

E-mail for Professor McLeod : hmcleod@iafrica.com

Editor’s Note

John Kendal submitted this work as his Honours research project in the Actuarial

Science Department at the University of Cape Town in 2003. John obtained a first for

his project (a rarity in Actuarial Science) and his work was submitted as one of the

best national actuarial projects in that year.

The purpose of his research was to ‘compare and explain’ the Australian and USA

risk based capital (RBC) systems and investigate, using the 2000 statutory returns

from the Office of the Registrar of Medical Schemes, the impact of application of

these systems in South Africa.

The most valuable and long-lasting part of this work is the definition of the data items

in the statutory returns to the Registrar that should be used in the RBC formulae from

the USA and Australia. This mapping was no small feat and this diligent work will

provide a valuable platform for the development of recommendations on a possible

RBC formula for South Africa.

In areas where there was no equivalent data item in South Africa, the author has

suggested an appropriate definition or indicated whether it is a meaningful omission.

This work was placed in Appendices C, D and E but should probably have merited a

chapter in its own right.

This is a very useful research report which will lay the foundations for RBC work in

medical schemes in the years to come.

The most important research work now needed is to determine the required overall

level of solvency for South African medical schemes. Work also needs to be done on

how the solvency standard for healthcare funds differs from the standard for managed

care organisations (the NAIC formula) in the USA and how this might be applied in

South Africa.

Once agreement is reached on the overall solvency needed in South African medical

schemes and managed care organisations, it will then be possible to undertake further

research on the appropriate level of certain key parameters in the formulae, based on

South African evidence.

Professor Heather McLeod

May 2004

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page ii

Synopsis

Risk-based capital (RBC) is a level of capital that enables a medical scheme to

withstand certain adverse fluctuations in results. It is determined by the risks facing a

scheme. This report examines two foreign methods for calculating RBC requirements

and estimates the impact a RBC system would have on South African medical scheme

solvency.

The USA and Australian RBC systems

The USA RBC system for Managed Care Organisations (MCO’s) is incredibly

detailed, but remarkably simple. It is based on a certain probability of ruin and

determines the RBC for an MCO, known as risk-based capital after covariance, by

multiplying its various balance sheet and income statement items by risk factors. A

special feature of this system is its allowance for risk-transfer through managed care

arrangements and reinsurance contracts.

The Australian system requires insurers to hold capital to meet certain circumstances.

This system resembles the current RBC system for South African life insurers and

would probably be similar to any RBC system developed for South African medical

schemes. It requires insurers to hold an amount of capital (i.e. the solvency reserve)

that will enable the fund to meet its current obligations if the fund was closed to new

business and run-off. It also requires the fund to hold sufficient capital (i.e. the capital

adequacy reserve) to meet its obligations as a going concern. Special features of this

system are its interaction with the Australian risk-equalisation system and its

specification of a method to estimate outstanding claims.

Impact of RBC on South African medical scheme solvency

Since no RBC system has been developed specifically for the South African medical

scheme industry, the impact of RBC on South African medical scheme solvency was

estimated by calculating the USA and Australian RBC requirements for South African

medical schemes using 2000 statutory returns data.

At the industry level, it is unclear whether a RBC system would require the industry

to hold more or less capital than the current 25% of gross contributions rule. The USA

RBC after covariance is less than 25% of gross contributions, while the Australian

solvency and capital adequacy reserves straddle the current requirement.

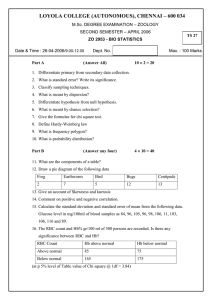

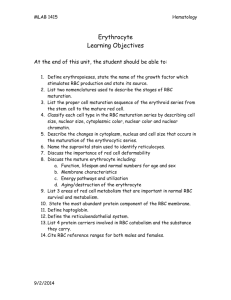

The figure below shows the USA and Australian RBC requirements as a percentage of

gross contributions for individual schemes.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page iii

70

Risk-based capital after covariance

Solvency reserve

60

Capital adequacy reserve

Accumulated funds

Number of schemes

50

40

30

20

10

0

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

45%

50%

55%

60%

65%

70%

75%

80%

85%

90%

95% 100% More

Percentage of gross contributions

Under both systems, some schemes are allowed to hold less than 25% of gross

contributions while others are required to hold significantly more. This implies that

some schemes would be strongly against a RBC system while others (especially the

larger schemes) would support it.

Conclusions

Despite the differences between the two foreign systems, they each have features that

could be useful in the South African environment. They also suggest what changes

should be made to the life insurance standards to make them applicable to medical

schemes. In addition, it appears that each RBC system will have a unique effect on

solvency at the industry level.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page iv

Table of Contents

Editor’s Note.................................................................................................................ii

Synopsis ........................................................................................................................iii

Table of Contents ......................................................................................................... v

Glossary .....................................................................................................................viii

1.

Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1

1.1

1.2

1.3

1.4

1.5

1.6

1.7

2.

Risk-Based Capital............................................................................................... 3

2.1

2.2

2.3

2.4

3.

Background to Research Project .................................................................... 1

Statement of Research Project ....................................................................... 1

Objectives of Research Project ...................................................................... 1

Sources of Information .................................................................................. 1

Scope and Limitations of Project ................................................................... 2

Plan of Development...................................................................................... 2

Acknowledgements ........................................................................................ 2

Introduction to Risk-Based Capital ................................................................ 3

Medical Scheme Risk .................................................................................... 4

Calculation of RBC Requirements................................................................. 5

Desirable Features of a RBC System ............................................................. 6

The USA RBC system for Managed Care Organisations ................................ 8

3.1

Introduction to the USA RBC System ........................................................... 8

3.2

Asset Risk – Affiliates ................................................................................... 9

3.3

Asset Risk – Other ....................................................................................... 10

3.3.1

Fixed income assets ............................................................................. 11

3.3.2

Replication transactions ...................................................................... 11

3.3.3

Equity ................................................................................................... 12

3.3.4

Property and equipment assets ............................................................ 12

3.3.5

Asset concentration .............................................................................. 13

3.4

Underwriting Risk ........................................................................................ 15

3.4.1

Base Underwriting risk RBC ............................................................... 15

3.4.2

Underwriting risk RBC after managed care discount ......................... 15

3.4.3

Alternative risk charge ......................................................................... 17

3.5

Credit Risk ................................................................................................... 18

3.6

Business Risk ............................................................................................... 21

3.7

Risk-Based Capital After Covariance .......................................................... 23

3.8

Transitional Arrangements........................................................................... 25

4.

The Australian RBC System for Private Health Insurers ............................. 27

4.1

4.2

4.3

4.4

CARE

Introduction to the Australian RBC System ................................................ 27

Solvency Liability ........................................................................................ 29

Expense Reserve .......................................................................................... 31

Inadmissible Assets Reserve ........................................................................ 32

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page v

4.5

4.6

4.7

4.8

4.9

4.10

4.11

4.12

5.

Resilience Reserve ....................................................................................... 34

Management Capital Amount ...................................................................... 35

Capital Adequacy Liability .......................................................................... 36

Renewal Option Reserve.............................................................................. 39

Business Funding Reserve ........................................................................... 40

Subordinated Debt Allowance ..................................................................... 40

Solvency and Capital Adequacy Reserves ................................................... 42

Transitional Arrangements........................................................................... 42

The effect of RBC on South African Medical Scheme Solvency ................... 44

5.1

Methodology ................................................................................................ 44

5.2

Industry Level .............................................................................................. 44

5.2.1

Aggregate solvency .............................................................................. 44

5.2.2

Aggregate solvency by scheme type ..................................................... 45

5.2.3

Aggregate solvency by scheme size...................................................... 47

5.3

Individual Scheme Level ............................................................................. 48

5.3.1

Range of individual scheme capital requirements ............................... 48

5.3.2

Individual scheme solvency by scheme type ........................................ 49

5.3.3

Individual scheme solvency by scheme size ......................................... 49

5.4

Summary ...................................................................................................... 50

6.

A Comparison of the Australian and USA RBC Systems .............................. 52

6.1

Conceptual Framework ................................................................................ 52

6.1.1

Probability of ruin................................................................................ 52

6.1.2

Capital to meet specific circumstances ................................................ 52

6.1.3

Suitable conceptual framework for a South African RBC system........ 53

6.2

Components of Each Formula ..................................................................... 53

6.2.1

Omissions from the USA formula ........................................................ 54

6.2.2

Omissions from the Australian formulae ............................................. 54

6.2.3

Relative sizes of the different components ........................................... 54

6.3

Special features of each formula .................................................................. 55

6.3.1

Special features of the USA formula .................................................... 55

6.3.2

Special features of the Australian formulae......................................... 57

6.4

Meeting the requirements ............................................................................ 57

6.5

Basis for intervention ................................................................................... 57

7.

Conclusions and Further Research .................................................................. 58

8.

References and Bibliography ............................................................................ 59

8.1

8.2

8.3

8.4

Australia ....................................................................................................... 59

United States of America ............................................................................. 60

South Africa ................................................................................................. 61

General ......................................................................................................... 62

Appendix A: Data Files Submitted to the Council for Medical Schemes ............. 63

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page vi

Appendix B: RBC Theory ......................................................................................... 64

B1. Calculation of RBC requirements using the EPD and probability of ruin

approaches................................................................................................................ 64

B1.1 Ruin Approach ............................................................................................. 64

B1.2 Expected policyholder deficit (EPD) approach .......................................... 65

B1.3 More complicated situations ....................................................................... 66

B2. Estimating factors by simulation ....................................................................... 66

B3. Solvency liability margin .................................................................................. 67

Appendix C: Method used to calculate the USA RBC Requirement .................... 69

C1. Statutory returns data used in the calculation.................................................... 69

C2. Treatment of the different types of guarantee ................................................... 71

C3. Assumptions and adjustments to the formula ................................................... 72

C3.1 Premium tiers .............................................................................................. 72

C3.2 Alternative risk charge ................................................................................ 73

Appendix D: Method used to calculate the Australian Solvency Reserve ............ 74

D1. Statutory returns data used in the calculation ................................................... 74

D2. Assumptions and adjustments to the formula ................................................... 75

D2.1 Asset concentration risk .............................................................................. 75

D2.2 Resilience reserve ....................................................................................... 75

D2.3 Management capital amount ....................................................................... 77

Appendix E: Method used to calculate the Australian Capital Adequacy Reserve

...................................................................................................................................... 78

E1. Statutory returns data used in the calculation .................................................... 78

E2. Assumptions and adjustments to the formula .................................................... 79

E2.1 General ........................................................................................................ 79

E2.2 Capital adequacy margin ............................................................................ 79

E2.3 Renewal option reserve ............................................................................... 81

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page vii

Glossary

Accumulated funds

The net asset value of a medical scheme, excluding funds set aside for specific

purposes and unrealised non-distributable reserves.

Affiliates

“A person or entity that directly, or indirectly through one or more other persons or

entities, controls, is controlled by, or is under common control with the reporting

entity.” (NAIC, 2001, 33)

Capital (also equity or net asset value)

For the purposes of this report, capital is defined to be total assets minus total

liabilities. Therefore, the terms capital, equity and net asset value will be used

interchangeably throughout this report.

Gross contributions

“Gross contributions are amounts (premiums) payable by members and/or employers,

in terms of the rules of the medical scheme, for the purchase of healthcare benefits.

Gross contributions include, savings plan contributions.” (SAICA, 2003, p.53)

Healthcare receivables

“Fee-for-service, coordination of benefits and subrogations, co-payments, and other

health balances.” (NAIC, 2001, p.34)

IBNR claims liability

This is the liability for future payments in respect of claims that have already been

incurred by the medical scheme but not yet reported in the scheme’s records, as well

as the expected future development on reported claims (ASSA, 2003).

Managed care

Refers to the use of management techniques to deliver appropriate healthcare in a

cost-effective manner, through the use of risk-sharing contractual arrangements with

healthcare providers and various other healthcare expenditure management

techniques.

Managed care healthcare benefits

This is the cost of healthcare services under payment systems such as capitations and

other contractual arrangements (SAICA, 2003)

Managed care management services expenses

This is the cost to the medical scheme of healthcare expenditure management services

such as disease and case management, pre-authorisation and bill review. This does not

include the cost of any healthcare services. (SAICA, 2003)

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page viii

Managed care organisation

“Any person, corporation or other entity which enters into arrangements or

agreements with licensed medical providers or intermediaries for the purpose of

providing, or offering to provide, a plan of health benefits directly to individuals or

employer groups in consideration for an advance periodic charge (premium) per

member covered.” (NAIC, 2001, p.34)

National Association of Insurance Commissioners

The regulator of, inter alia, USA MCO’s

Net contributions

“Net contributions represent contributions for which the medical scheme is at risk,

and are calculated as gross contributions less savings contributions, during the

accounting period.” (SAICA, 2003, p.54)

Outstanding claims

Outstanding claims consist of claims that have been:

Incurred but not reported (IBNR);

Reported but not yet settled or approved for payment;

Reported and administratively finalised but which may be reopened. (ASSA,

2002).

Private Health Insurance Administration Council

The regulator of Australian private health insurers

Probability of ruin

The probability of insolvency

Registered medical scheme

Any medical scheme that is or will be in full compliance with the Medical Schemes

Act of 1998, and is registered with the Council for Medical Schemes (Dreyer, 2001).

The Registrar

The Registrar of medical schemes, appointed under section 18 of the Medical

Schemes Act of 1998

Reinsurance

A contractual arrangement under which some of the risk of the medical scheme is

transferred to a reinsurer in return for some consideration (ASSA, 2002)

Risk

Risk is the possibility of adverse deviations in results.

Risk-Based Capital

Risk-based capital is the minimum amount of capital a medical scheme must hold to

ensure that the danger of insolvency is acceptably low. It is an amount of capital that

enables an entity to survive certain adverse fluctuations in results.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page ix

Risk charge

The amount of risk-based capital required by a risk element or collection of risk

elements.

Risk element

Distinct, quantifiable elements that differ in their level of risk are known as different

risk elements (Butsic, 1994). For example, bonds, equities and property are three

different risk elements.

Risk factor (also RBC factor)

The risk factor for a certain risk element is the ratio of its risk charge to the value of

that risk element. They are related to risk charges and the value of a risk element by

the following equation:

Risk charge = Value of Risk element Risk factor.

Technical insolvency (also insolvency or ruin)

Technical insolvency occurs when a scheme’s liabilities exceed its assets.

Abbreviations

ASC

ASO

ASSA

HBFCAR

HBFSR

IBNR

MCO

NAIC

PHIAC

RBC

RBCAC

RBCBC

SAICA

SEU

CARE

Administrative services contract

Administrative services only

Actuarial Society of South Africa

Health benefits fund capital adequacy requirement

Health benefits fund solvency requirement

Incurred But Not Received

Managed Care Organisation

National Association of Insurance Commissioners

Private Health Insurance Administration Council

Risk-Based Capital

Risk-Based Capital After Covariance

Risk-Based Capital Before Covariance

South African Institute of Chartered Accountants

Single Equivalent Unit

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page x

1. Introduction

1.1 Background to Research Project

A medical scheme is solvent if its assets exceed its liabilities. For the purpose of

regulation, a more stringent definition of solvency is used. This is meant to expose

schemes that might become insolvent or experience financial distress in the future so

that the regulator may take appropriate corrective action. In SA, for a scheme to be

solvent under the regulator’s definition of solvency, it must hold accumulated funds in

excess of 25% of gross contributions.

In a study of solvency requirements for medical schemes, Cooper (2001) points out a

number of problems with this regulatory solvency measure. For instance, it ignores

the transfer of risk through managed care contracts and reinsurance agreements. It

also ignores scheme size and variability in claims experience. In short, it makes no

allowance for the differing risk profiles of medical schemes. Cooper concluded that

the current solvency approach is inappropriate. He recommended the adoption of a

risk-based approach, which would consider the specific risks faced by each scheme.

He also recommended that the solvency definition allow for the transfer of risk.

1.2 Statement of Research Project

In light of Cooper’s recommendations, this project will examine two foreign riskbased capital systems and attempt to establish the effect a risk-based capital system

would have on South African medical scheme solvency.

1.3 Objectives of Research Project

The objectives of this project are to:

1. Explain and compare the RBC systems of Australian Health Insurers and USA

Managed Care Organisations.

2. Use 2000 statutory returns data to establish the effect a RBC system would

have on South African medical scheme solvency.

1.4 Sources of Information

Legislative and regulatory documents provided the basic detail of the Australian and

USA RBC systems, while journal articles on risk-based capital systems proved useful

in understanding the formulae and RBC in general.

Email was used to contact foreign RBC experts who were extremely helpful in

explaining certain parts of the formulae and providing reference papers.

The Registrar’s 2000 statutory returns provided the data to estimate the effect a RBC

system would have on South African medical scheme solvency.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 1

1.5 Scope and Limitations of Project

This report explains the Australian and USA RBC formulae and establishes the effect

those RBC systems would have on South African medical scheme solvency if

implemented without adaptation. It does not aim to develop a RBC system for South

African medical schemes or to adapt the foreign systems for use in the South African

medical scheme industry.

The project was limited in places by data availability and international differences.

Some of the data required by the Australian and USA RBC formulae was not

available from the Registrar’s 2000 returns, which meant that assumptions and

approximations were necessary. Furthermore, of the 146 schemes that were registered

in 2000, only 144 submitted their 2000 returns.

In addition, the report only considers the effect a RBC system would have on

Registered scheme solvency. It ignores Bargaining Council scheme solvency.

1.6 Plan of Development

The report begins with an introduction to risk-based capital in general. It then looks at

two foreign risk-based capital systems in detail. Chapter 3 gives an account of the

USA RBC formula for Managed Care Organisations, while Chapter 4 explains the

Australian solvency and capital adequacy standards for private health insurers. In

Chapter 5, data from the 2000 statutory returns is used to estimate the impact of RBC

on South African medical scheme solvency. This is achieved by calculating the USA

and Australian RBC requirements for South African medical schemes. Chapter 6 then

compares the Australian and USA systems. Finally, conclusions are reached and

recommendations are made for further research.

1.7 Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank his supervisor, Professor McLeod of the University of

Cape Town, for her expertise, enthusiasm and supervision of this project.

Thanks must also go to:

Alan Ford of the American Academy of Actuaries;

David Watson of the Health Practice Committee of the Institute of Actuaries of

Australia;

Paul Groenewegen and Gayle Ginnane of the Australian Private Health Insurance

Administration Council;

Maggie Grobler of the Council for Medical Schemes; and

Mahesh Cooper

for their selfless assistance and valuable insights.

The author is also grateful to Yura Kaliazin for his comments on an earlier version of

this report.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 2

2. Risk-Based Capital

The aim of this chapter is to introduce the idea of risk-based capital. This will set the

scene for the next two chapters where two foreign RBC systems are discussed.

2.1 Introduction to Risk-Based Capital

Capital provides a cushion that allows a medical scheme to remain solvent through

certain adverse fluctuations in results. The more capital a scheme holds, the less likely

it is to go insolvent. The following diagram takes this relationship one step further by

introducing risk.

Capital

Risk

Probability of

ruin

Source: Van Den Heever (1998)

Figure 2.1: The relationship between capital, risk and probability of ruin

A medical scheme’s probability of ruin (or probability of insolvency) depends on the

risks that it faces as well as the amount of capital it holds. Two schemes facing the

same risks but holding different quantities of capital will have different ruin

probabilities. By changing the amount of risk and/or capital held, schemes can

influence their probability of ruin, making this a three-way relationship.

Under a risk-based capital (RBC) system, the relationship is simpler. The regulator

would choose the maximum probability of ruin and then, by examining a scheme’s

risk profile, determine the minimum amount of capital required by that scheme to

achieve that probability of ruin. The figure below shows the relationship from the

regulator’s point of view.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 3

Minimum

Capital

Requirement

Probability of

ruin

Risk

Figure 2.2: The relationship between risk, capital and probability of ruin from the regulator’s

point of view

Risk-based capital is the minimum amount of capital a medical scheme must hold to

ensure that the probability of ruin is acceptably low. This minimum amount of

capital is determined by the risks affecting the medical scheme.

Under a risk-based capital system, medical schemes would be required to hold capital

in excess of some minimum capital requirement (the RBC requirement) determined

by the regulator. If a scheme’s capital fell below the required level, it would be

subject to regulatory action of some kind.

2.2 Medical Scheme Risk

If each medical scheme were required to hold a minimum amount of capital

determined by its risk profile, it would be natural to ask: “what risks should be taken

into account when setting these minimum capital requirements?” This section looks at

the various risks affecting medical schemes and will provide a point of reference for

the risks considered by the foreign RBC formulae in the coming chapters. Hooker

(1996), Cooper (2001) and the Council For Medical Schemes (2003) provided

valuable input to this section.

The main risks affecting medical schemes are:

Uncertainty in claims costs; and

Asset risk.

Uncertainty in claims costs relates to the potential error in estimates of incurred

claims for business already written and the potential error in estimates of future claims

used to price new business. For instance, the outstanding claims liability on the

balance sheet may be understated because incurred claims have been underestimated.

Restating the liabilities will reduce the scheme’s capital and may result in insolvency.

Also, new business may be under-priced because actual claims turn out to be higher

than was expected when contributions were set. The resulting losses will reduce the

scheme’s capital and could, if severe enough, cause insolvency.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 4

Asset risk is another major risk for a medical scheme. The scheme assets are invested

in the financial markets, so their capital values and income returns (e.g. dividends) are

likely to fluctuate. A decline in capital value will reduce the equity on a scheme’s

balance sheet and may lead to insolvency. Also, if the income from the assets is lower

than expected, the scheme may have to sell other assets to meet claim payments. This

will also reduce the scheme’s equity and could potentially cause insolvency.

Poor liquidity of assets, caused by poor asset structure, may render the scheme unable

to pay claims as they arise. Asset risk is intensified by excessive concentration of

assets in particular asset classes or with particular issuers.

Apart from the main risks already mentioned, medical schemes face many other risks,

including:

The risk of catastrophic losses;

Expense risk;

Managed care risk;

Reinsurance risk;

Credit risk;

Management risk; and

Growth risk.

The first two risks are self-explanatory. Managed care risk is the risk that a Managed

Care Organisation (MCO) defaults on its obligations to the scheme. This could

happen if the scheme paid capitations to an MCO which went insolvent before

providing the agreed care to the scheme members.

Reinsurance risk relates to the possibility that the reinsurer will not pay future

reinsurance claims in full. It includes the risk that the reinsurer may not pay those

claims currently outstanding in full. Credit risk is similar and refers to the risk of other

creditors defaulting on their obligations to the scheme.

Management risk relates to the possibility that a scheme’s management is incompetent

to run the scheme effectively. Areas that could be mismanaged include claims

processing, investment, benefit design and financial reporting.

Growth risk is present when a scheme grows quicker than its resources. In the UK

general insurance context, Hooker (1996) highlights inadequate infrastructure and

expertise as possible consequences of rapid growth into a new geographical area.

2.3 Calculation of RBC Requirements

Once the regulator has identified the risks affecting a particular scheme, that

information can be used to calculate its RBC requirement. The next two chapters will

describe exactly how this is done in the United States and Australia.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 5

At a theoretical level, there are three possible approaches:

The probability of ruin approach (used by the USA RBC system);

The expected policyholder deficit approach; and

The approach whereby schemes are required to hold capital to meet certain

circumstances (used by the Australian RBC system).

Appendix B1 gives an example of how the first two methods work. Section 2.1

introduced the idea of RBC using the probability of ruin approach for ease of

explanation.

2.4 Desirable Features of a RBC System

Hooker (1996) and Cummins et al (1992) suggest that a RBC system should be:

An incentive for weak companies to hold more capital and/or reduce risks without

distorting the behaviour of financially sound schemes;

Comprehensive;

Based on a solid theoretical foundation;

Free of unnecessary complexity;

Robust; and

Unlikely to cause adverse behavioural changes such as manipulation of financial

results.

They also acknowledge that some of these qualities are conflicting. The coming

paragraphs will expand on these points.

The main aim of a risk-based capital system is to give financially weak schemes an

incentive to reduce the danger of insolvency. It should encourage those schemes for

which market incentives are insufficient, to reduce risk and/or hold more capital.

More often than not this will cause the schemes to increase contribution rates.

To avoid distorting the behaviour of financially sound insurers, the level of the RBC

requirement must be set carefully. A high requirement will reduce insolvencies, but

distort the behaviour of financially sound insurers and cause large increases in

contribution rates. If the requirement is set too low, it will have no impact on

insolvencies.

The formula should be “comprehensive” or complete in that it includes as many

different risks as possible. It should allow for the various steps schemes can take to

mitigate risks, such as reinsurance arrangements and managed care arrangements.

Likewise, the formula should recognise how schemes can exacerbate these risks, such

as excessive concentration of assets in a certain asset class or with a certain issuer.

Examples of solid theoretical foundations are the probability of ruin approach and the

newer expected policyholder deficit approach. These approaches were both mentioned

in the previous section.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 6

Any RBC formula should be free from complexity that only marginally increases the

accuracy of the formula. This will make the formula easier to explain, understand and

use. Cummins et al (1993) point out that the more complex the formula, the more

difficult it will be for schemes to determine the effect of their actions on their required

capital. A complex formula could also lead to unintended side effects when the

formula is put into practice, since it is harder to predict the effect of a complicated

formula than the effect of a simple formula. Practically speaking, the benefits and

costs of additional data reporting under a complex system need to be evaluated.

The formula should also be “robust” in the sense that a minor change in a firm’s risk

profile should cause no more than a minor change to that firm’s RBC requirement.

Robustness helps ensure that the RBC system does not cause undesirable changes to

scheme behaviour by creating incentives to manipulate financial results. Furthermore,

the RBC requirement should not cause schemes to take unnecessary additional risks.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 7

3. The USA RBC system for Managed Care

Organisations

This chapter explains the USA RBC system for Managed Care Organisations

(MCO’s).

3.1 Introduction to the USA RBC System

The USA RBC system calculates the amount of capital an MCO needs to ensure its

probability of ruin is sufficiently low. This capital will enable the MCO to withstand

certain adverse fluctuations in results. Although quite detailed, the formula is

conceptually simple. The following example (ASSA, n.d.) will give an initial feel.

Suppose an MCO invests all its assets in bonds and that the current value of this

investment is $100 million. Next, assume that there is a 5% probability that the value

of this investment will be less than $75 million in one year’s time and that the MCO

has liabilities of $75 million. This implies that the MCO must hold at least $25

million in capital to have a 95% probability of remaining solvent over the coming

year (assuming asset risk is the only risk faced by the scheme). If capital requirements

are based on a 5% probability of ruin, the MCO will have a $25 million RBC

requirement.

In this example, a risk factor of 0.25 (i.e. 25/100) would be appropriate for bonds. In

other words, the risk charge for bonds equals 0.25 multiplied by the value of the

MCO’s bond portfolio.

The USA RBC formula uses this risk factor approach to specifying the various risk

charges. Most risk charges in the USA formula are of the form:

Risk charge = Value of Risk element Risk factor.

Risk elements are items that differ in their riskiness. In the above example, bonds are

the risk element. Common stock, preferred stock and equities are other risk elements

that would each require a different factor, the riskier the risk element, the larger the

risk factor. Appendix B2 explains how these factors would be estimated in practice.

The formula is divided into five sections, each one corresponding to a different risk.

This structure is illustrated below.

RBC requirement

Asset risk

H0: Asset risk - affiliates

Liability risk

H1: Asset risk - other

H2: Underwriting risk

Other risks

H3: Credit risk

H4: Business risk

Source: NAIC (2001)

Figure 3.1: Structure of USA RBC formula

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 8

Each section contains the various risk elements relating to that risk. These risk

elements require different risk factors to determine their risk charges.

The total risk charges for each section of the formula are combined to give the riskbased capital after covariance (RBCAC) for an MCO. If an MCO’s total equity

exceeds its RBCAC, the MCO is not subject to any regulatory action. However, if an

MCO’s equity falls below one of four thresholds, the organisation will be subject to

regulatory action. These different thresholds and their corresponding regulatory

actions are shown in the table below. Authorised Control Level (ACL) is defined as

50% of an organisation’s RBCAC.

Table 3.1: RBC thresholds and their corresponding regulatory actions

RBC level

Company Action Level

(CAL=200% ACL)

Regulatory action

The company must notify the insurance commissioner of the corrective

actions it plans to take to increase capital.

Regulatory Action Level

(RAL=150% ACL)

The company must submit or resubmit a corrective plan of action to remedy

the situation. After examining the company, the insurance commissioner will

issue an order specifying the corrective actions to be taken.

The insurance commissioner is authorised to take whatever regulatory action

Authorised Control Level

is necessary to protect the interests of the policyholders, including taking

(ACL)

control of the company.

Mandatory Control Level The insurance commissioner is required to place the company under

regulatory control.

(MCL=70% ACL)

Source: Milliman (1998, p.2)

The following sections will explain each of the five sections of the USA formula; the

calculation of risk-based capital after covariance; and the transitional arrangements

used to phase in this RBC requirement. Data from South African medical schemes’

2000 statutory returns are used throughout these sections to give a feel for how much

RBC the formula would have required registered South African medical schemes to

hold at 31 December 2000. This will also demonstrate the relative importance of the

different sections.

3.2 Asset Risk – Affiliates

This section of the RBC formula allows for the risk that the value of investments in

affiliates will decrease. Therefore, this section only affects MCO’s that have

ownership in affiliates. South African medical schemes are essentially mutual

organisations, so they cannot have a parent. They could however have a subsidiary,

but this is rare.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 9

The risk charge for ownership in affiliated entities depends on whether those entities

are themselves subject to a RBC requirement. For affiliates that are not subject to

RBC, holdings in non-USA insurance subsidiaries receive a risk factor of 1.0, while

other affiliates have a risk factor of 0.3. For affiliates that are subject to RBC, the risk

charge is more complicated. Since it has little relevance to the South African

environment, its full detail will not be set out here and the reader is referred to NAIC

(2001, pp.1-6). Suffice it to say, the aim of the risk charge for investment in affiliated

entities is to ensure that the assets held in respect of the affiliate’s capital requirements

are not counted in meeting the capital requirements of its owner.

The asset risk – affiliates section also makes allowance for off balance sheet risk such

as contingent liabilities that are disclosed in the notes to the financial statements. It

calculates the risk charge by applying a 0.01 factor to the value of the contingent

liability. By holding extra capital in respect of these contingent liabilities it reduces

the risk of the MCO going insolvent, were it required to make any payments in terms

of these contingent liabilities.

The estimated value of the asset risk – affiliates charge for registered South African

medical schemes is shown below.

Table 3.2: Estimate of asset risk – affiliates RBC

Rands

Off-balance sheet items

189,718

H0: Asset risk - affiliates RBC

189,718

Gross contributions

29,884,077,939

% of gross contributions

0.001%

Clearly, the asset risk – affiliates charge would not impose a significant capital

requirement on South African medical schemes.

3.3 Asset Risk – Other

Figure 3.2 shows the structure of the Asset risk – other section.

Asset risk - other

Fixed income assets

Replication transactions

Equity

Property and equipment

Asset concentration

Source: NAIC (2001)

Figure 3.2: Structure of asset risk – other charge

This section reserves against reductions in the market value of assets as well as the

possibility of default of principal or interest. It only deals with unaffiliated

investments. This part of the formula is very detailed because it differentiates between

many different types of assets. For instance, it recognises seven different bond classes,

and assigns each one a different risk factor.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 10

This can make the formula appear more complex than it actually is. It also makes

estimation of these risk factors (i.e. calibrating the formula) time consuming and

expensive.

Despite the level of detail in this section, all the risk charges are of the form:

Risk charge = Value of Risk element Risk factor.

The total risk charge for the asset risk – other section of the RBC formula is found by

summing the risk charges for each of its five subsections.

3.3.1 Fixed income assets

The NAIC Security Valuations Office (SVO) classifies bonds into six different classes

based on their risk of default of principal and interest. These bond ratings are used in

the formula. The riskier bonds are allocated to the higher classes, so the higher the

bond class, the higher the risk factor for that bond. The figure below shows the risk

factors used for fixed income assets.

0.35

0.300

0.3

0.25

Risk factor

0.200

0.2

0.15

0.100

0.1

0.045

0.05

0.020

0.000

0.003

0.010

0.003

0.003

Cash

Other short

term

investments

0

Government Class 1 bonds Class 2 bonds Class 3 bonds Class 4 bonds Class 5 bonds Class 6 bonds

bonds

Other long

term

investments

Risk element

Source: NAIC (2001)

Figure 3.3: Fixed income asset risk factors

3.3.2 Replication transactions

The formula recognises that some assets are held for the purposes of replicating the

payoffs from derivatives. It handles these assets differently from normal holdings. The

reader is referred to NAIC (2001, p.9) for the detail of this part of the formula.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 11

3.3.3 Equity

The formula distinguishes between common stock and preferred stock. As for bonds,

preferred stock is divided into six categories. Because there was no experience data

available to determine the preferred stock factors, they were set at the bond factor

level plus 2%, subject to a maximum of 30%. This was based on the assumption that

preferred stocks are more likely to default than bonds and that the losses on preferred

stock default would be higher than that on bonds (NAIC, 2001). Problems such as

lack of data to estimate factors are made more likely by the level of detail in the

formula. The resulting preferred stock and common stock factors are shown in the

figure below.

0.35

0.300

0.3

Risk factor

0.25

0.2

0.150

0.15

0.120

0.1

0.065

0.05

0.040

0.023

0.030

0

Class 1 preferred

stock

Class 2 preferred

stock

Class 3 preferred

stock

Class 4 preferred

stock

Class 5 preferred

stock

Class 6 preferred

stock

Common stock

Risk element

Source: NAIC (2001)

Figure 3.4: Equity risk factors

The factor for common stock lies between the factors for class five and six preferred

stock. On the whole, the formula recognises that common stock is more risky than

preferred stock, as one would expect

3.3.4 Property and equipment assets

Milliman (1998) state that one of the unique characteristics of MCO’s is investment in

property, such as hospitals, that are used for the provision of care and may give the

MCO greater control over healthcare costs. The formula appears to take this into

account by dividing properties into:

“Properties occupied by the company;

Properties held for the production of income; and

Properties held for sale.” (NAIC, 2001, p.12)

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 12

However, each category has a risk factor of 0.1, so for asset risk RBC purposes, it

doesn’t matter which category the MCO’s property falls into. Furthermore, the

underwriting risk section of the formula (see section 3.4) is unaffected by these

property categories. This implies that the formula ignores any increased control over

healthcare costs that an MCO enjoys from owning property.

Furniture and equipment are divided into:

Heath care delivery assets and

Other furniture and equipment.

Vehicles would be included in the second category (A. Ford, personal

communication, May 2, 2003).

As for property, both categories have a risk factor of 0.1. It is surprising that this risk

factor is lower than the common stock factor (0.150). This seems to suggest that

investment in furniture and equipment is less risky than investment in common stock.

At first glance it may seem pointless to distinguish between different types of assets

and then treat them in the same way. It is the author’s opinion that the NAIC plan to

assign different risk factors to the various equipment and property types in the future,

but have not yet decided what these factors should be (perhaps due to lack of data).

3.3.5 Asset concentration

The asset concentration section of the formula imposes an additional charge for high

concentrations of certain types of assets with single issuers. This is because there is

increased risk of insolvency if one of these issuers should default. An issuer is “a

single entity, such as IBM or Ford Motor Company” (NAIC, 2001, p.13).

Concentrated investments in certain types of assets are not expected to increase the

risk of insolvency significantly. Such assets are exempt from the asset concentration

charge. Assets subject to the concentration charge include:

Bonds (class 2-5);

Preferred stock (class 1-5);

Other long-term invested assets; and

Common stock.

The asset concentration charge effectively doubles the risk factor (up to a maximum

of 0.3) for assets held with the ten largest issuers. The ten largest issuers are

determined based on the total value of the assets that are subject to the concentration

charge invested with each issuer. By doubling the risk charge for these issuers, we

decrease the probability that reductions in the value of these assets will cause

insolvency.

Estimated values of the different components of the asset risk – other charge for

registered South African medical schemes are shown below.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 13

Table 3.3: Estimate of asset risk – other RBC

Fixed income assets

Equity

Property and equipment

Asset concentration

H1: Asset risk - other RBC

Gross contributions

% of gross contributions

Rands

465,973,565

350,013,388

26,262,894

512,443,800

1,354,693,647

29,884,077,939

4.5%

The contributions of the different subsections of the asset risk – other charge are

shown in Figure 3.5.

1.9%

25.8%

37.8%

Asset concentration

Fixed income assets

Equity

Property and equipment

34.4%

Figure 3.5: Components of asset risk – other charge

The asset concentration charge is the largest contributor to asset risk – other. This is

because many schemes were not invested across more than ten issuers, so the asset

concentration charge made up almost half of their asset – risk other charges. Fixed

income assets and equity assets are the other main contributors. Schemes hold very

little property and equipment, so these components were not significant.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 14

3.4 Underwriting Risk

The underwriting risk charge is usually the largest single component of the RBC

requirement and it is based on the risk that incurred claims may be higher than

expected. The underwriting risk charge is the maximum of the underwriting risk RBC

after managed care discount and the alternative risk charge.

3.4.1 Base Underwriting risk RBC

Base underwriting risk RBC is calculated separately for each line of business. It is

determined by the following equation:

Underwriting risk revenue Claims ratio Risk factor.

Underwriting risk revenue is essentially contributions net of reinsurance premiums, so

the formula allows for the transfer of risk through reinsurance. The credit risk (H3)

section of the formula allows for the possibility that the reinsurer may default on its

obligations to the MCO.

The claims ratio has the effect of reducing the underwriting risk charge for schemes

with better claims experience than others. Furthermore, it separates out the part of

premiums that are meant to cover claims from the part meant to pay expenses (ASSA,

n.d.). Expenses are dealt with separately in the business risk (H4) section of the

formula.

The risk factor is a premium weighted average of 0.15 and 0.09. The first $25 million

of premiums are used to weight the 0.15 factor while the rest apply to the 0.09 factor.

Other things equal, the risk factor and consequently the risk charge is lower for

schemes with larger total premiums. Barth (1999) suggested this tiered approach in

his article “Applying the Law of Large Numbers to P&C Risk-Based Capital”. He

argued that the variability of a loss ratio is lower for insurers with larger risk pools.

He quantified this relationship by regressing loss ratio standard deviation on earned

premium. The tiered factors were then chosen based on this relationship.

3.4.2 Underwriting risk RBC after managed care discount

This section of the formula adjusts the base underwriting risk RBC for the transfer of

risk from the MCO to the healthcare provider through managed care contracts.

Underwriting risk RBC after managed care discount is:

Base Underwriting Risk RBC Managed care discount factor.

The following table shows the different managed care categories and discount factors.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 15

Table 3.4: Managed care credit categories

Category

Description

Fee-for-service, discounted fee-for-service and other non-managed care

0

arrangements.

Factor

0.00

1

Payments made under contractual arrangements such as hospital per diems,

physician fee schedules, DRG-based payments, case rates, and other

contractual arrangements that would not apply to category 0.

0.15

2

Payments made subject to withholds and bonuses. The managed care credit

factor is presented as a range based on the proportion of withholds and bonuses

paid. The minimum factor is the managed care credit factor for category 0 or 1,

depending on the reimbursement method to which the withholds pertain. The

maximum managed care credit factor is 0.25.

0.00-0.25

3

Capitation payments made directly to providers of medical care and capitations

paid to intermediaries, such as an IPA, who, in turn, make payments to

providers who contract independently with the intermediary (not including

employment contracts). This includes payments to physicians and nurses for

utilisation review.

0.60

4

Owned facility expenses and salaries paid directly to medical care providers and

noncontingent salaries or aggregate cost payments to licensed providers.

0.75

Source: Milliman (1998, p.6)

The total paid claims in each category are used as weights to determine the weighted

average of the discount factors in the third column. Paid claims are used instead of

incurred claims because of the variability in estimates of outstanding claims included

in incurred claims as well as the difficulty in allocating estimated outstanding claims

to the different managed care categories. The managed care discount factor is then

defined as one minus this weighted average. It lies between zero and one.

It is important to realise that this reduction in the risk charge is based on a reduction in

the variability of claim payments caused by risk sharing agreements. It is not due to

any reduction in the size of claims. Notice how the managed care arrangements that

pass on more risk to the providers are assigned higher factors, which imply a smaller

underwriting risk charge. As with reinsurance, the credit risk section allows for the

possibility that the counter-parties to these contracts default on their obligations to the

MCO.

The figure below shows the breakdown of registered South African medical schemes’

paid claims between managed care and non-managed care arrangements.

The 99% of paid claims that were paid under non-managed care arrangements would

be grouped into category zero. Most of the 1% of paid claims made under managed

care arrangements would probably be grouped into categories zero or one.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 16

1.0%

Non-managed care claims

Managed care claims

99.0%

Figure 3.6: Managed care claims as a percentage of paid claims

Many of the managed care initiatives used by South African schemes have been found

not to transfer any risk at all. Doherty and McLeod (2002) found that in 2001, only

13% of medical schemes used risk-sharing managed care arrangements. All this

suggests that the managed care discount would currently have very little effect on

South African medical schemes at present.

[Editor’s Note: the use of risk-sharing arrangements is changing rapidly and the

conclusion above is made too lightly. An allowance for managed care risk transfer

makes sense IF managed care organisations in South Africa become regulated for

solvency. They could be required to hold reserves using a similar RBC approach.]

3.4.3 Alternative risk charge

The other component of the underwriting risk section of the formula is the alternative

risk charge. This reduces the probability that an MCO will be ruined by large

individual claims. The alternative risk charge is twice the maximum after reinsurance

payout on any individual claim.

The underwriting risk section of the formula also makes allowance for many different

types of business that USA MCO’s write that fall under the umbrella of medical

insurance and are not the business of a medical scheme.

An estimate of the underwriting risk charge for registered South African medical

schemes is shown below.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 17

Table 3.5: Estimate of underwriting risk RBC

Base underwriting risk RBC

Base underwriting risk RBC after

managed care discount

Alternate risk charge

H2: Underwriting risk RBC

Gross contributions

% of gross contributions

Rands

2,700,546,872

2,695,639,592

247,160,000

2,713,030,121

29,884,077,939

9.1%

Notice how small the effect of the managed care discount is. The underwriting risk

charge would impose a capital requirement of 9.1% of gross contributions on medical

schemes.

One of the author’s initial, but incorrect, criticisms of the USA RBC formula was that

it did not allow for the risk of misestimating outstanding claims. Mr. Alan Ford, one

of the creators of the formula, explained via email that the underwriting risk charge

implicitly includes a reserve against misestimating outstanding claims. An extract

from that email is included below.

“The answer to your question is that the H2 Factor includes

provision for the misestimating of outstanding claims.

RBC represents a level of capital that indicates a MCO's ability to

withstand adverse fluctuation in results. For MCO's the H2 risk is

primarily for the adverse deviation of incurred claims, which

includes the change in estimates for outstanding claims over the

valuation period as well as paid claims. Generally, outstanding

claims are estimated as a function of the paid claims over the

valuation period, adjusted for changes in claim backlog and other

known factors. The estimates of outstanding claims and the paid

claims are intimately related, so providing separate risk factors for

the components would introduce unnecessary complexity into the

determination of RBC.”

Alan Ford, personal communication, 27 February, 2003

3.5 Credit Risk

The credit risk section of the formula is divided into three subsections as shown in

Figure 3.7.

Credit risk

Reinsurance

Capitations

Other receivables

Source: NAIC (2001)

Figure 3.7: Structure of credit risk charge

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 18

Reinsurance risk is the possibility that the reinsurer will not pay the amounts it

currently owes the MCO, as well as the possibility that it will not provide the future

cover already paid for by the portion of the reinsurance premium that is currently

unearned. The reinsurance risk factor is 0.005, which is applied to amounts due from

reinsurers and premiums paid in advance to reinsurers. This risk factor is only

marginally higher than the cash factor of 0.003, suggesting that banks and reinsurers

have similar security. As for property, the reinsurance section divides reinsurance

receivables into various categories, but then assigns them all the same 0.005 factor.

Presumably, the NAIC intends to assign different factors to these different receivables

in future.

Capitation risk is present when an MCO pays capitations to providers or

intermediaries. It is possible that the provider or intermediary will not provide the

agreed upon services and the MCO will be forced to pay other providers to provide

these services. Withholds and letters of credit from providers can mitigate this risk.

The formula takes this into account by making some capitations exempt from the risk

charge when these measures are in place. The example in the table below shows how

the risk charge is calculated for capitations paid directly to providers. The risk charge

for capitations paid to intermediaries is calculated similarly.

Table 3.6: Example of calculation of capitation credit risk charge

Name of provider

Dr. A

Dr. B

Dr. C

Dr. D

Total risk charge

A

B

C

D=(B+C)/A E=A*Min(1,D/8%)

F=A-E

G=F*0.02

Paid

Capitation to

capitations Letter of

providers

during the

credit

Funds Protection

Exempt

subject to risk

Risk

year

amount witheld percentage

capitations

charge

charge

125,000

5,000

0

4%

62,500

62,500

1,250

50,000

5,000

0

10%

50,000

0

0

750,000

5,000

50,000

7%

687,500

62,500

1,250

25,000

0

0

0%

0

25,000

500

3,000

Source: NAIC (2001, p.26)

If the capitations are secured by letters of credit and withholds equal to 8% of paid

capitations, the entire capitation is exempt. Where less protection is provided, the

exempt capitation is prorated. A risk factor of 0.02, which is equivalent to one week’s

paid capitations, is applied to the remaining capitations. This seems to imply that

some mixture of withholds and letters of credit equal to 8% of the paid capitation

provides similar security to capital equal to 2% of the paid capitation. It is the author’s

opinion that this risk charge and its concessions are based more on experience and

judgement than statistics and data analysis.

The other receivables risk charge reserves against the risk that certain receivables will

be irrecoverable. It applies a 0.01 factor to investment income receivable and a 0.05

factor to health care receivables and amounts due from affiliates. A notable omission

from this section is any allowance for arrear contributions. When questioned on this,

Mr. Ford gave the following response.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 19

“Due and unpaid (arrear) premiums are not included in the RBC

calculation. Generally speaking, (in my opinion) this is not a large

risk. The aging of this receivable item is included in a separate

exhibit on the blank, so the regulator can readily discern where

assets are ‘optimistic’ with respect to the aging. Also, this

receivable is only admitted if it is under 90 days.”

Alan Ford, personal communication, 2 May, 2003

In the year 2000, some of the arrear contributions included in South African medical

schemes accounts receivable were more than 120 days in arrears. This suggests that

South African medical schemes are more exposed to this risk than are USA MCO’s.

Estimates of the different components of the credit risk charge for registered South

African medical schemes are shown in the table below.

Table 3.7: Estimate of credit risk RBC

Rands

Reinsurance RBC

1,774,818

Other receivables RBC

14,080,589

H3: Credit risk RBC

15,855,407

Gross contributions

29,884,077,939

% of gross contributions

0.1%

The credit risk charge is only 0.1% of gross contributions, so it would not impose a

significant capital requirement on medical schemes. The pie chart below shows the

relative importance of its two components.

11.2%

Other receivables RBC

Reinsurance RBC

88.8%

Figure 3.8: Components of credit risk charge

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 20

The other receivables charge, based mainly on co-payments due from members,

dominates the credit risk charge. Capitation risk is absent since this data was

unavailable. Since only 13% of medical schemes used risk sharing managed care

arrangements in 2001 (Doherty & McLeod, 2002) it is not expected to be significant.

3.6 Business Risk

The business risk section of the formula is divided into three subsections as illustrated

below.

Business risk

Administrative expense risk

Non-underwritten and limited risk

Excessive growth risk

Source: NAIC (2001)

Figure 3.9: Structure of business risk section

When premiums are set they include an assumption about the level of future

administrative (i.e. non-claims) expenses. These expenses are unknown at the time

premiums are set, so their variability leads to a risk charge.

The administrative expense charge is of the form:

Previous year’s administrative expenses Risk factor.

The risk factor is a tiered factor, similar to the underwriting risk factor. It is a

weighted average of 0.07 and 0.04, where the first $25 million of premiums is used to

weight the 0.07 factor while premiums in excess of $25 million weight the 0.04 factor.

The effect of this is to reduce the administrative expense risk charge for larger

schemes, which are expected to have less fluctuation in their administration expenses.

USA MCO’s can act as administrators for third parties, performing administrative

services such as claims processing. This type of business is known as “nonunderwritten and limited-risk business”. In this regard, the RBC formula differentiates

between administrative services only (ASO) and administrative services contracts

(ASC). Under an ASO contract, the MCO only pays claims once the third party has

paid the MCO enough money to fully cover the claims. Under an ASC contract, the

MCO would pay claims first and seek reimbursement from the third party afterwards.

Administrative expenses relating to ASC and ASO contracts are assigned a risk factor

of 0.02. This is lower than the factor for the MCO’s own administrative expenses.

This is probably because the MCO is only concerned with claims administration

under these contracts, allowing less scope for variability in expenses. Furthermore, a

0.01 factor is applied to total claims payments made under ASC contracts on behalf of

third parties. This risk charge stems from the risk that the counter party to the ASC

contract may be unable or unwilling to reimburse the MCO for claims payments made

under the contract.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 21

This risk charge has implications for South African medical scheme administrators. If

a RBC formula similar to the USA formula were introduced in South Africa, third

party administrators, as well as MCO’s and medical schemes, would be obliged to

hold minimum amounts of capital.

The final part of the business risk section is the excessive growth charge, which aims

to penalise uncontrolled growth. It does this by comparing the underwriting risk RBC

to a notional “safe level”. The formula sets the maximum safe level of underwriting

risk RBC by growing the previous year’s underwriting risk RBC for one year at the

one-year growth rate in premiums plus 10%. The excessive growth charge is then

defined as 50% of the difference between the current underwriting risk RBC and the

maximum safe level, subject to a minimum of zero.

Professor McLeod pointed out a problem with this method of reserving against

excessive growth (personal communication, April 3, 2003). If a scheme has a large

increase in membership shortly before the date on which the RBC requirement is

calculated, the extra premiums from these new members will not be fully visible at the

calculation date. Therefore, the underwriting risk RBC will not have increased

sufficiently to generate an excessive growth charge.

An estimate of the business risk charge for registered South African medical schemes

is shown in the table below.

Table 3.8: Estimate of business risk RBC

Administrative expense RBC

Excessive growth RBC

H4: Business risk RBC

Gross contributions

% of gross contributions

Rands

124,379,325

177,549,064

301,928,389

29,884,077,939

1.0%

The business risk charge would impose a capital requirement of roughly one percent

of gross contributions. The relative sizes of the different subsections of the business

risk charge are shown below.

The excessive growth charge and administrative expense charge both contribute

significantly to the business risk charge. The non-underwritten and limited risk

business charge was not applicable to South African medical schemes. Such risk

charges relate more to the business of scheme administrators than medical schemes.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 22

41.2%

Excessive growth RBC

Administrative expense RBC

58.8%

Figure 3.10: Components of business risk charge

3.7 Risk-Based Capital After Covariance

The risk-based capital after covariance (RBCAC) is a level of capital that allows the

MCO to withstand various adverse circumstances, as defined by the earlier five

sections of the formula. Since it is unlikely that these five circumstances coincide, the

RBCAC is less than the sum of these five sections.

RBCAC is determined by the following formula:

RBCAC H 0 H12 H 2 2 H 32 H 4 2 .

It assumes that the H1, H2, H3 and H4 risks are uncorrelated, while the H0 (affiliates)

risk is highly correlated with the other four risks. The following example (ASSA, n.d.)

will show how these assumptions are used.

Suppose an MCO has two risk elements, A and B, with risk charges of R3 million and

R4 million respectively. Assume that the risk charge for a given element is set so that

if the MCO faced only that risk and held exactly that amount of capital it would have

a 5% probability of ruin. Therefore, if an MCO had risk element A only and exactly

R3 million in capital, it would have a 5% probability of ruin.

CARE

Effect of RBC Formulae on Medical Scheme Solvency

Page 23

For a scheme with both risk elements, the capital requirement for a 5% probability of

ruin would be

3 2 4 2 2 Correlatio n( RiskA, RiskB ) 3 4 .

Case 1: If A and B are perfectly positively correlated, the capital requirement for a

5% probability of ruin is R7million (i.e. 3+4).

Case 2: If A and B are uncorrelated, the capital requirement is R5 million (i.e.

32 4 2 ).

The covariance adjustment is the cause of much debate. Van den Heever (1998) wrote

that there should be a covariance adjustment but that this square root rule is somewhat

arbitrary. On the other hand, Butsic (1994) has derived this square root rule exactly by

assuming that the values of the risk elements are normally distributed. In addition,

Hooker (1996) recommended that there should be no overall covariance adjustment,

but there should be an adjustment for covariance within the asset risk charge. Hooker

based this recommendation on his opinion that the absolute level of a RBC

requirement is a political decision based on what the market can handle.

The table below shows the total RBC after covariance and its components for

registered South African medical schemes.