Cuban legal structures facilitating urban agriculture: Adaptation for the New South

advertisement

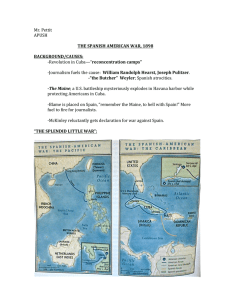

Cuban legal structures facilitating urban agriculture: Adaptation for the New South Wales local government context Liesel Spencer School of Law, University of Western Sydney l.spencer@uws.edu.au 14.8.2013 Local government – a lot of responsibilities, not a lot of resources The ‘Councils’ Charter’: s 8 Local Government Act 1993 (NSW) Integrated Planning and Reporting Framework: Ch 13 Local Government Act 1993 (NSW) Regulatory power and statutory planning Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW) ‘Co-benefits’ • “An additional benefit from an action that is undertaken to achieve a particular purpose, that is not directly related to that purpose.” • Meeting public (human) health and environmental health responsibilities at the same time • Making councils’ resources stretch further Why public health is an urgent issue for Australian governments • Epidemic of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) • Economic forecasting (on the record in both NSW and Victorian Parliaments) that by 2030, the entire State budget could be absorbed by health costs Cuba – 1990s economic crisis • Soviet withdrawal of oil and US trade embargo – ‘Special Period’ • Agriculture previously dependent on oil – legacy of the ‘Green Revolution’ – industrial agriculture – monocultures (mostly sugarcane for export) with heavy inputs of imported fertiliser and pesticides – soil degradation and resistant pests • Government response – changed agricultural model; break up of state farms into cooperatives; rationing Cuba – public health outcomes and environmental health outcomes • By internationally recognised measures, Cuba is a model of sustainability and a model of public health • Low carbon footprint plus acceptably high quality of life – only country to achieve this • Low incidence of coronary disease, diabetes, infant mortality • A nation-scale public health experiment no ethics committee would approve! Cuba – agricultural model • ‘Agroecology’ and La Via Campesina – minimal external inputs and outputs • Organic (integrated management – substitute inputs) • Permaculture • Cuban government is now giving up to 13.5 ha to families interested in taking up agroecological farming Cuba – urban agriculture • Havana and other cities 40-60% selfsufficiency in fresh vegetables • 383,000 urban farms covering 50,000ha of otherwise unused land producing more than 1.5million tons of vegetables • Job creation: over 350,000 new jobs in urban agriculture programs Cuba – legal structures supporting urban agriculture • Break-up of state owned farms into cooperatives • Unidades Basicas de Produccion Cooperativas Permanent usufruct rights – rent free use of state owned land, ownership of crops produced Cuba – legal structures supporting urban agriculture • Organoponicos Started in military facilities as a food security measure Raised container garden beds for intensive production Organic methods Construction materials and compost provided by the State Occupy unused land all over the capital cities Cuba – legal structures supporting urban agriculture • Los Mercados Agropecuarios A free market for sale of produce direct to purchaser No state intervention Growers obtain highest monetary return for labour Translation to the NSW local government context • • • • • • • Public land and public open space ‘Commons’ Cooperatives Community Supported Agriculture (CSAs) Verge gardens Community gardens Local government already does these things: Community garden on Housing Commission land, Riverwood NSW Farmers’ markets – North Sydney and Marrickville, NSW Community fruit tree grove, Unanderra, NSW – community centre grounds Verge gardens – Chippendale NSW How can councils in NSW achieve more with urban agriculture, by applying aspects of the Cuban model? • empowerment of the individual with selforganisation and horizontal knowledge transfer • secure access to land; stable possession of land • For urban agriculture to work, people need to be given both forms of ‘ownership’ Self-organisation and horizontal knowledge transfer • The ‘people’ side of urban agriculture • Campesino-a-campesino model in Cuba • Learning organic urban agriculture from other urban farmers – incl. traditional knowledge • Cooperatives – community groups • Autonomy and control over work • e.g. successful model in local public schools in the Illawarra – ‘Living Classrooms’ Secure access to land; stable possession of land • Cuban experience – urban farmers (and rural farmers) had faster uptake of organic and agroecological practices, and higher productivity, in the cooperative farming model, which gave stable long term rights over specific areas of land • Local government has statutory power to grant long term leases over public land Using LG law to give secure, stable access to public land for urban agriculture • Public land is classified as ‘community’ or ‘operational’ under s 26. • Community land further categorised, according to use, s 36 LGA, including ‘general community use’ • Local Government (General) Regulation 2005 (NSW) Part 4 – lease and licence of community land Urban agriculture and statutory purpose • A categorisation of ‘general community use’ under s 36I aims to ‘to promote, encourage and provide for the use of the land, and to provide facilities on the land, to meet the current and future needs of the local community and of the wider public, in relation to public recreation and the physical, cultural, social and intellectual welfare or development of individual members of the public, and in relation to purposes for which a lease, licence or other estate may be granted in respect of the land’. Conclusion • Local government has limited resources and large responsibilities including public health and environmental protection • NCDs are a public health crisis • Cuba is the only country in the developed world to have managed the balance of human health and quality of life, and environmental sustainability • Nation-scale implementation of urban agriculture, backed by government, is significantly responsible for Cuba’s positive outcomes • Cuban legal structures for urban agriculture can be adapted to the NSW local government context as a strategy to meet councils’ statutory public health and environmental protection responsibilities