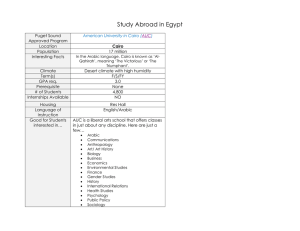

The American University in Cairo A Thesis Submitted by

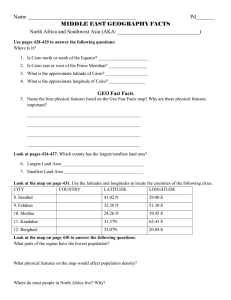

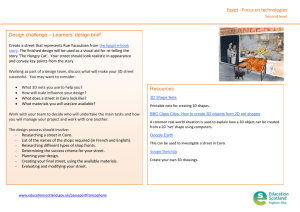

advertisement