The American University in Cairo A Thesis Submitted by

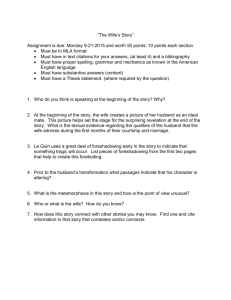

advertisement