[Running Head: The City as Context] Wendy Cadge, Brandeis University

advertisement

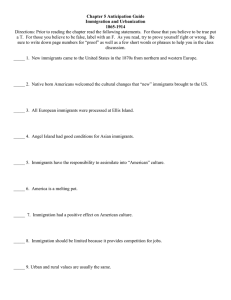

![[Running Head: The City as Context] Wendy Cadge, Brandeis University](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/015505803_1-13c35538577a5a8214eca71d49065821-768x994.png)