bonino_soriguer_2009.doc

advertisement

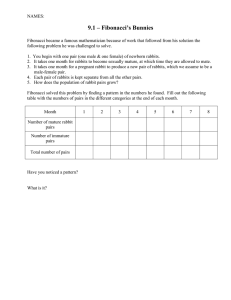

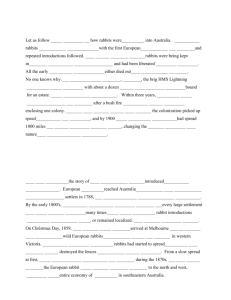

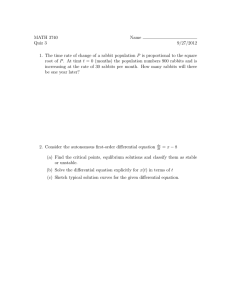

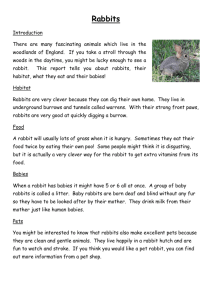

The invasion of Argentina by the European wild rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus NEVE R B O N IN O * and RA M ÓN S O R I G U E R † *Estación Experimental Bariloche (INTA), C.C. 277, 8400 Bariloche, Argentina, †Estación Biológica Doñana (CSIC), Av. María Luisa s/n, 41013 Sevilla, España ABSTRACT 1. We provide an updated distribution and dispersal rate of the introduced European rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus in Argentina. 2. According to our results this invasive species is currently colonizing parts of Mendoza and Neuquén Provinces, where rivers are very important in the spread of the rabbits, especially in unfavourable areas. The maximun rate of dispersal registered in this study was 9 km/year. 3. Some information was obtained to indicate that the presence of this exotic species threatens agriculture, livestock, forestry, and natural ecosystems of the Patagonia region. Keywords: biological invasions, dispersal, exotic species, invasive species, Oryctolagus cuniculus INTRODUCTIO N Invasive species are a global problem, affecting agriculture, forestry, fisheries, human health and natural ecosystems (Mooney & Drake, 1986; Drake et al., 1989; Sandland, Schei & Viken, 1999; Mack et al., 2000; Pimentel, 2002). The European wild rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus is one of the most widely distributed invasive species (Flux & Fullagar, 1992) and provides one of the best examples of the disastrous consequences that can result from the introduction of an exotic species (Thompson & King, 1994; Williams et al., 1995; Bomford & Hart, 2002; Clout, 2002). A species native to south-western Europe, the European rabbit has been introduced into different regions of the world including Asia, Australia, New Zealand and North and South America (Flux, 1994). On this last continent, rabbits were introduced into several regions of Chile, from which they invaded the south-western part of Argentina (Howard & Amaya, 1975; Zunino, 1989). In Argentina, the rabbits are now present in three regions (Fig. 1). 1. Tierra del Fuego – Falkland (Malvinas) Islands According to Jaksic & Yáñez (1983), the first introduction to Tierra del Fuego was made in about 1880 onto a number of islands in the Beagle Channel. The original stock came from the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands, onto which rabbits had been introduced by the French prior to 1765. Some of these Channel island rabbits were set free in about 1936 on the Chilean side of Tierra del Fuego. In around 1950 more rabbits were released on the Argentinian side of this Correspondence: N. A. Bonino. E-mail: nbonino@bariloche.inta.gov.ar Fig. 1. Current distribution of the European wild rabbit in South America. The dark grey area marks the range in Chile; the light grey area the range in Argentina. 1 = Tierra del Fuego and Falkland (Malvinas) Islands, 2 = Santa Cruz Province, 3 = Mendoza and Neuquén Provinces. island (Arentsen, 1954). Within a few years these introductions proved disastrous: rabbits quickly became a pest, riddling the ground with holes and leaving it bare of grass. The sheep ranchers attempted to control the rabbits first by hunting and trapping, then by introducing the mainland fox Pseudalopex griseus, which did not naturally occur on Tierra del Fuego. Later they brought myxoma virus from Brazil, and this virus succeeded in bringing rabbits to very low population levels (Jaksic & Yáñez, 1983). 2. Santa Cruz Province In 1985 rabbits were detected at the south-western edge of this province (Clarke & Amaya, 1986). Presumably they had come from nearby Puerto Natales (Chile), where several animals (apparently originating from Tierra del Fuego) were released in 1970 (A. Iriarte Walton, personal communication). These rabbits have apparently not dispersed widely, as their current distribution is still restricted to the south-western part of this province. 3. Mendoza and Neuquén Provinces In 1945 rabbits were first reported in these provinces. They originated from animals that crossed through low passes in the Andean Cordillera from adjacent parts of central Chile. These central Chilean rabbits are of Spanish origin and had been introduced at the beginning of the 19th century (Greer, 1965; Howard & Amaya, 1975). Within these two provinces, the rabbit is currently dispersing and invading new areas (Bonino & Gader, 1987; Bonino & Soriguer, 2004). A fundamental approach to understanding and managing invasive species is to determine their geographical distribution. The current distribution of the European rabbit in Mendoza and Neuquén Provinces and their dispersal rate are reported here. MATE RI AL S AND MET HOD S The distribution of the European rabbit in Mendoza Province was described by Bonino & Soriguer (2004). In Neuquén Province we performed field sampling on the basis of the map of rabbit distribution in 1986 (Bonino & Gader, 1987). For the present surveys, undertaken between November 2006 and April 2008, the rural inhabitants of the perimeter of the mapped distribution area were visited. We asked them about the presence or absence of rabbits in the surrounding area. At the same time we directly surveyed the land, searching for sightings or signs of individuals such as faeces, burrows and skeletons. All the information was georeferenced by using a GPS unit. Afterward, this information was entered into a digitalized map in order to determine the current geographical distribution and the dispersal rate of this invasive species. R E S UL T S A ND D IS C U SSI O N In the eastern sector of the distributional area in Neuquén Province, we observed the dispersal of this species mainly along the banks of rivers that flow through the region, generally from east to west (Fig. 2). According to Bonino & Gader (1987) the front of the advance along the Colorado River had progressed to about 20 km east of Rincón de los Sauces. In this study, Rincón Colorado (37°33′45″S, 68°23″32″W) was the easternmost site where rabbits were observed along the margins of this river (Fig. 2). According to information from the local inhabitants, this exotic species causes damage, mainly in orchards and crops of alfalfa. Along the margins of the Neuquén River, rabbits were found at Sauzal Bonito (Bonino & Gader, 1987) and also near the bridge at Dique Portezuelo (38°26′22″S, 68°57′19″W). Previously, rabbits had been located on the Picún Leufú River near the town of the same name (Bonino & Gader, 1987), but in this study we observed that they had advanced up to where this river flows into the Limay River and have begun to disperse both upstream and downstream of this latter river. Also, rabbits were observed in Ojo de Agua (39°38′20″S, Fig. 2. Dispersal of the European wild rabbit in the Mendoza and Neuquén Provinces, Argentina. The dark grey area shows the distribution in 1986; the light grey area represents dispersal during the 1986–2008 period. 69°29′19″W) and along the margins of the China Muerta stream, another affluent of the Limay River (Fig. 2). In each case the dispersal rate was less than 5 km/year. In the southern part of the distributional area (Fig. 2), the limit was at the Estancia Pulmarí (39°06′41″S, 71°06′32″W) according to Bonino & Gader (1987). However, in this study rabbits were detected about 175 km further south, in the surroundings of the Meliquina Lake (40°22′39″S, 71°18′89″W). Also, at a site (40°21′36″S, 70°39′22″W) located on the left margin of the Collon Curá River, a few kilometers before its entry into the Limay River, faeces and burrows of rabbits were observed. These records indicate a dispersal rate that varied between 6 and 9 km/year. Figure 2 shows the importance of rivers in the spread of this invasive species, especially in unfavourable areas. The western part of the distributional area consists of Andean forests and subandean grasslands. The eastern sector supports scrub formation (Monte Botanical Province) in a semi-desert environment with annual rainfall under 200 mm, where soils are stoney or gravely (Soriano, 1983). The most irregular distributional pattern is found in this arid region where the rabbits live in places bordering the rivers and small streams, as also happens in the arid habitats of Australia (Myers & Parker, 1975a,b; Myers et al., 1994). As was noted by Bonino & Soriguer (2004) in Mendoza Province, the rabbit is also currently undergoing a process of dispersal in Neuquén Province. The environments already colonized in the western part of this province are being occupied, with a little variation, towards the south of the region as far as Santa Cruz Province. Therefore, we predict that in the future this exotic species will invade the whole Patagonian region. Considering that the areas occupied by the rabbit in Neuquén Province are very important for the provincial economy, the situation may worsen since, according to inhabitants of the region, the rabbit competes with cattle for food and causes considerable damage to alfalfa crops, orchards and coniferous forest plantations. The establishment of the rabbit in some protected areas (Lanín and Laguna Blanca National Parks) and its potential invasion into others (Nahuel Huapi National Park) poses a threat for the wild fauna of these areas. The presence of this exotic herbivore, with its semi-fossorial habit and high reproductive rate (Myers & Calaby, 1977), could harm some of the native species directly, through competition for food and/or shelter, or indirectly, by favouring increases in the populations of native carnivores (Novaro, Funes & Walker, 2000; Novaro & Walker, 2005). In Australia and New Zealand, the rabbit is considered an important threat to the integrity of the ecosystems of arid zones (Bomford & Hart, 2002; Clout, 2002), and there are numerous examples of the negative impact of this species on the native flora and fauna (Dawson & Ellis, 1979; Leigh et al., 1987, 1989; Lunney & Leary, 1988; Burbidge & MacKenzie, 1989; Auld, 1990; Morton, 1990; Mutze et al., 2008). The maximum rate of dispersal registered in this study was 9 km/year, similar to the 10 km/year reported by Bonino & Gader (1987). The values cited for other countries where the rabbit was introduced are highly variable: in Australia, dispersal varied between 15 km/ year in denser woodlands of the eastern and southern regions and 300 km/year along the drainage channels in the Simpson Desert (Strong, 1983; Myers et al., 1994); and in New Zealand, rabbits spread at a rate of 16 km/year (Gibb & Williams, 1994). The available literature on dispersal rates of introduced mammals in different parts of the world, although not abundant, is also variable: Sciurus carolinensis achieved a rate of 7.7 km/ year in south-western England (Williamson & Brown, 1986); Ondatra zibethicus had variable rates between 1 and 25 km/year, depending on the region, in Europe (Andow et al., 1990; Van de Bosch, Hengeveld & Metz, 1992) and between 3.9 and 10.8 km/year in Chile and Argentina (Jaksic et al., 2002); Sigmodon hispidus had an average rate of 8.8 km/year in the USA (Genoway & Schlitter, 1967); Castor canadensis dispersed from 3.1 to 6.3 km/year in Chile and Argentina (Jaksic et al., 2002); and Cervus canadensis and Rupicapra rupicapra dispersed from 0.6 to 8.7 km/year, respectively, in New Zealand (Caughley, 1963). A close relative to the European rabbit, the European hare Lepus europaeus, has dispersed into South America from 10 to 44 km/year, depending on the specific regions invaded (Cossios, 2004; Bonino, Cossios & Menegheti, 2008). The role of human intervention in the process of rabbit dispersal is not well understood, although it could favour such a process. For example, it is known that sometimes animals are liberated (intentionally or not) from domestic (breeding) colonies and this action could facilitate further invasion of this exotic species. Some populations of a still strictly local character that are found in several Argentine provinces (Chubut, San Juan and Río Negro) result from liberation of rabbits by humans. CON CLUSIONS We document a notable increase in the European wild rabbit distribution area in the Patagonia region of Argentina. Therefore, regular and careful monitoring is necessary for the early detection and management of newly established populations. European rabbits are potentially a significant threat to agriculture, livestock, forestry and natural ecosystems. Thus, the continued study of this invasive species in Argentina is warranted. The development of a predictive model of the potential distribution and the ecological impacts of rabbits would be invaluable. At present there is no information regarding the ecological impact of the European rabbit in natural ecosystems, and scant information on other aspects of its biology and ecology, in Argentina (Bonino, 2006). ACKNOWL ED GE ME NT S We thank R.D. Sage and B.B. Cooke for constructive comments on an earlier draft and two anonymous reviewers who provided helpful suggestions. Fieldwork was funded by the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET PIP 937) and the Programa de Cooperación Científica con Iberoamérica (AECI). REFERENCE S Andow, D.A., Kareiva, P.M., Levin, S.A. & Okubo, A. (1990) Spread of invading organisms. Landscape Ecolology, 4, 177–188. Arentsen, P. (1954) Control biológico del conejo. Boletín Ganadero No. 4, Punta Arenas, Chile. Auld, T.D. (1990) Regeneration in populations of the arid zone plants Acacia carnei and A. oswaldii. Proceedings of the Ecological Society of Australia, 16, 267–272. Bomford, M. & Hart, Q. (2002) Non-indigenous vertebrates in australia. In: Biological Invasions: Economic and Environmental Costs of Alien Plant, Animal and Microbe Species (Ed. by D. Pimentel), pp. 25–44. CRC Press, New York, USA. Bonino, N. (2006) Estado actual del conocimiento sobre la liebre europea y el conejo europeo introducidos en la Argentina. INTA EEA Bariloche, Argentina, Comunicación Técnica Fauna, 61, 1–29. Bonino, N. & Gader, R. (1987) Expansión del conejo silvestre europeo (Oryctolagus cuniculus) en la Rep. Argentina y perspectivas futuras. Anales del Museo de Historia Natural, Valparaíso, Chile, 18, 157–162. Bonino, N. & Soriguer, R. (2004) Distribución actual y dispersión del conejo europeo (Oryctolagus cuniculus) en Mendoza (Argentina). Mastozoología Neotropical, 11, 237–241. Bonino, N., Cossios, D. & Menegheti, J. (2008) Dispersión de la liebre europea (Lepus europaeus) en Sudamérica. INTA EEA Bariloche, Argentina, Comunicación Técnica Fauna, 152, 1–8. Burbidge, A.A. & Mackenzie, N.L. (1989) Patterns in the modern decline of Western Australia’s vertebrate fauna: causes and conservation implications. Biological Conservation, 50, 143–198. Caughley, G. (1963) Dispersal rate of several ungulates introduced into New Zealand. Nature, 200, 280–281. Clarke, R. & Amaya, J. (1986) Presencia del conejo silvestre (Oryctolagus cuniculus) en la prov. de Santa Cruz. INTA EEA Río Gallegos, Argentina, Memorias Técnicas, 2, 89–93. Clout, M.N. (2002) Ecological and economics costs of alien vertebrates in New Zealand. In: Biological Invasions: Economic and Environmental Costs of Alien Plant, Animal and Microbe Species (Ed. by D. Pimentel), pp. 185–194. CRC Press, New York, USA. Cossios, D. (2004) La liebre europea, Lepus europaeus (Mammalia, Leporidae), especie invasora en el sur del Perú. Revista Peruana de Biología, 11, 209–212. Dawson, T.J. & Ellis, B.A. (1979) Comparison of the diets of yellow-footed rock-wallabies and sympatric herbivores in western New South Wales. Australian Wildlife Research, 6, 245–254. Drake, J.A., Mooney, H.A., di Castri, F., Groves, R.H., Kruger, F.J., Rejmanek, M. & Williamson, M. (1989) Biological Invasions: A Global Perspective. John Wiley and Sons, New York, USA. Flux, J.E.C. (1994) World distribution. In: The European Rabbits: the History and Biology of a Successful Colonizer (Ed. by H.V. Thompson & C.M. King), pp. 8–21. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. Flux, J.E.C. & Fullagar, P.J. (1992) World distribution of the rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus on islands. Mammal Review, 22, 151–205. Genoway, H.H. & Schlitter, D.A. (1967) Northward dispersal of the hispid cotton rat in Nebraska and Missouri. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science, 69, 356–357. Gibb, J.A. & Morgan Williams, J. (1994) The rabbit in New Zealand. In: The European Rabbit: The History and Biology of a Successful Colonizer (Ed. by H.V. Thompson & C.M. King), pp. 158–204. Oxford Science Publications, Oxford, UK. Greer, J.K. (1965) Mammals of Malleco Province, Chile. Publications of the Museum, Michigan State University, Biological Series, 3, 49–152. Howard, W.E. & Amaya, J. (1975) European rabbit invades western Argentina. Journal of Wildlife Management, 39, 757–761. Jaksic, F.M. & Yáñez, J.L. (1983) Rabbit and fox introduction in Tierra del Fuego: history and assessment of the attempts at biological control of the rabbit infestation. Biological Conservation, 26, 367–374. Jaksic, F.M., Iriarte, J.A., Jiménez, J.E. & Martínez, D.R. (2002) Invaders without frontiers: cross-border invasions of exotic mammals. Biological Invasions, 4, 157–173. Leigh, J.H., Wimbush, D.J., Wood, D.H., Holgate, M.D., Slee, A.V., Stanger, M.G. & Forrester, R.I. (1987) Effects of rabbits grazing and fire in a subalpine environment. I: Herbaceous and shrubby vegetation. Australian Journal of Botany, 35, 433–464. Leigh, J.H., Wood, D.H., Holgate, M.D., Slee, A.V. & Stanger, M.G. (1989) Effects of rabbits and kangaroo grazing on two semi-arid grassland communities in central-western New South Wales. Australian Journal of Botany, 37, 375–396. Lunney, D. & Leary, T. (1988) The impact on native mammals of land-use changes and exotic species in the Bega district New South Wales since settlement. Australian Journal of Ecology, 13, 67–92. Mack, R.N., Simberloff, D., Lonsdale, W.M., Evans, H., Clout, M.N. & Bazzaz, F.A. (2000) Biotic invasions: causes, epidemiology, global consequences, and control. Ecological Applications, 10, 689– 710. Mooney, H.A. & Drake, J.A. (1986) Ecology of Biological Invasions of North America and Hawaii. SpringerVerlag, New York, USA. Morton, S.R. (1990) The impact of European settlement on the vertebrate animals of arid Australia: a conceptual model. Proceedings of the Ecological Society of Australia, 16, 201–213. Mutze, G., Bird, P., Cooke, B. & Henzell, R. (2008) Geographic and seasonal variation in the impact of rabbit haemorrhagic disease on European rabbits, Oryctolagus cuniculus, and rabbit damage in Australia. In: Lagomorph Biology: Evolution, Ecology and Conservation (Ed. by P.C. Alves, N. Ferrand & K. Hackländer), pp. 279–293. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. Myers, K. & Calaby, J.H. (1977) The rabbit. In: The Australian Encyclopaedia (Ed. by The Grolier Society), pp. 157–162. The Grolier Society of Australia, Sydney, Australia. Myers, K. & Parker, B.S. (1975a) A study of the biology of the wild rabbit in climatically different regions in eastern Australia. VI. Changes in numbers and distribution related to climate and land systems in semiarid north-western New South Wales. Australian Wildlife Research, 2, 11–32. Myers, K. & Parker, B.S. (1975b) Effect of severe drought on rabbit numbers and distribution in a refuge area in semiarid north-western New South Wales. Australian Wildlife Research, 2, 103–120. Myers, K., Parer, I., Wood, D. & Cooke, B. (1994) The rabbit in Australia. In: The European Rabbit: the History and Biology of a Successful Colonizer (Ed. by H.V. Thompson & C.M. King), pp. 108–157. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. Novaro, A.J. & Walker, R.S. (2005) Human-induced changes in the effect of top carnivores on biodiversity in the Patagonian steppe. In: Large Carnivores and Biodiversity Conservation (Ed. by J.C. Ray, K.H. Redford, R.S. Steneck & J. Berger), pp. 267–287. Island Press, Washington DC, USA. Novaro, A.J., Funes, M.C. & Walker, R.S. (2000) Ecological extinctions of native prey of a carnivore assemblage in Argentine Patagonia. Biological Conservation, 92, 25–33. Pimentel, D., ed. (2002) Biological Invasions: Economic and Environmental Costs of Alien Plant, Animal, and Microbe Species. CRC Press, Boca Raton, USA. Sandland, O.T., Schei, P.J. & Viken, A., eds. (1999) Invasive Species and Biodiversity Management. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. Soriano, A. (1983) Deserts and semi-deserts of Patagonia. In: Temperate Deserts and Semi-deserts (Ed. by N.E. West), pp. 423–460. Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Strong, B.W. (1983) The invasion of the Northern Territory by the wild European rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus. Technical Report No. 3, Conservation Commission of the Northern Territory. Alice Spring, Northern Territory. Thompson, H.V. & King, C.M. (1994) The European Rabbit: The History and Biology of a Successful Colonizer. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. Van de Bosch, F., Hengeveld, R. & Metz, J.A.J. (1992) Analysing the velocity of animal range expansion. Journal of Biogeography, 19, 133–150. Williams, C.K., Parer, I., Coman, B., Burley, J. & Braysher, M. (1995) Managing Vertebrate Pests: Rabbits. Bureau of Resource Sciences/CSIRO Division of Wildlife and Ecology, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, Australia. Williamson, M. & Brown, K.C. (1986) The analysis and modeling of British invasions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society Series B, 314, 505–522. Zunino, S. (1989) Origen y distribución de los conejos en Chile. Boletín del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Chile, 316, 8–10. Submitted 17 March 2009; returned for revision 30 March 2009; revision accepted 28 May 2009 Editor: KH