$002fj$002fmamm.2008.72.issue-4$002fmamm.2008.051$002fmamm.2008.051.doc

advertisement

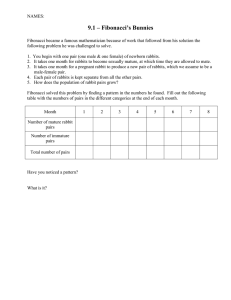

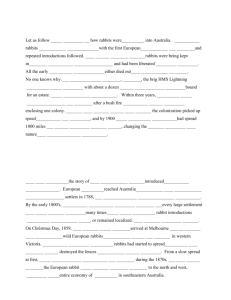

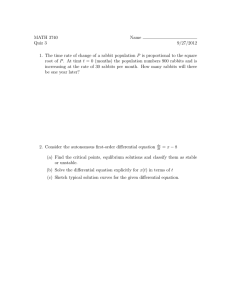

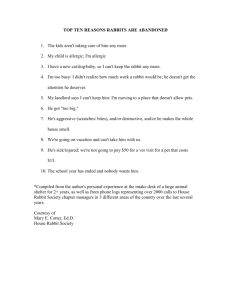

Genetic lineages of feral populations of the Oryctolagus cuniculus (Leporidae, Lagomorpha) in Argentina Never A. Bonino1,* and Ramón C. Soriguer2 Estación Experimental Bariloche, Instituto Nacional de Tecnologı́a Agropecuaria, Casilla de Correo 277, 8400 Bariloche, Rı´o Negro, Argentina, e-mail: nbonino@bariloche.inta.gov.ar 2 Estación Biológica Doñana, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientı́ficas, Avda Marı´a Luisa s/n, Pabellón Perú, 41013 Sevilla, España 1 * Corresponding author Keywords: European rabbit; genetic; introduced species; mitochondrial DNA; Patagonia. Both wild and domestic European rabbit belong to the single species Oryctolagus cuniculus, which is the sole extant representative of the genus Oryctolagus (Chapman and Flux 1990, Wilson and Reeder 2005). Two subspecies are recognized, O.c. algirus and O.c. cuniculus; they are well differentiated with respect to mtDNA (Branco et al. 2000), the Y chromosome (Geraldes et al. 2005) and some allozyme loci (Ferrand and Branco 2006). When judged only on their mitochondrial DNA, 22 different rabbit haplotypes are recognized and organized into two very divergent maternal lineages named A (corresponding to O.c. algirus) and B (corresponding to O.c. cuniculus). And within each lineage, there sublineages that are geographically substructure. Lineage A is found in the south-west of the Iberian Peninsula. Lineage B is distributed throughout the rest of Europe (including northern Spain), and in most populations introduced to other regions of the world (Ennafaa et al. 1987, BijuDuval et al. 1991, Monnerot et al. 1994). A clear subdivision into two groups was also found when nuclear genes were studied (Van der Loo et al. 1991, 1999) with a geographical distribution that largely coincides with that of the mitochondrial clades A and B. Rabbits of both lineages are very similar in their external appearance, although B lineage animals are somewhat larger (Rogers et al. 1994). All domestic rabbits belong to this B lineage, i.e., to subspecies O.c. cuniculus (Monnerot et al. 1996). The European rabbit has been introduced in different regions of the world including Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and North and South America (Flux 1994). In this last continent, rabbits were first introduced into several regions of Chile from which they invaded the southwestern region of Argentina (Howard and Amaya 1975, Zunino 1989). In Argentina, the rabbits are now present in three regions (Figure 1): 1) Tierra del Fuego Province, 2) Santa Cruz Province and 3) Mendoza-Neuquén Provinces. 1) Tierra del Fuego Province: according to Jaksic and Yañ ez (1983), the first introduction was made about 1880 onto a number of islands in the Beagle Channel. The original stock of these Channel animals came from the Falkland Islands, onto which rabbits had been introduced by the French prior to 1765. Some of these rabbits were set free around 1936 on the Chilean side of Tierra del Fuego, and around 1950 more were released on the Argentinan side of this island (Arentsen 1954, Goodall 1979). 2) Santa Cruz Province: in 1985 the rabbits were detected at the southwestern edge of this province (Clarke and Amaya 1986). Presumably they come from nearby Puerto Natales (Chile), where several animal (apparently originating from Tierra del Fuego) were released in 1970 (A. Iriarte Walton, personal communication). 3) Mendoza-Neuqué n Provinces: in 1945 the rabbits were first reported in these provinces. They originated from animals that crossed through low passes in the Andean Cordillera from adjacent parts of central Chile. These central Chilean rabbits are of Spanish origin and had been introduced at the beginning of the 20th century (Greer 1965, Howard and Amaya 1975). Within these two provinces, the rabbit is currently undergoing a process of dispersion and invasion of new areas (Bonino and Gader 1986, Bonino and Soriguer 2004). Therefore, rabbits inhabiting the southernmost two regions of Argentina are likely to be of French origin, whereas rabbits of the third northern region are likely to be of Spanish origin. Therefore, we studied the mitochondrial DNA of rabbits of these introduced populations to identify the maternal lineages. A total of 64 rabbits were shot in the three geographic areas where there are wild populations of European rabbit in Patagonia. The geographic locations of the populations sampled are shown in Figure 1 and collecting localities are given in Table 1. A portion of liver or muscle tissue was taken from freshly killed animals and stored in 70% ethanol. Total DNA was obtained following the method described by Rico et al. (1992) and used directly for amplification. Rapid discrimination between mtDNA haplotypes was carried out using diagnostic sites in two mtDNA fragments (565 bp from the cytochrome b gene digested with AluI and 586 bp from the non-coding region, digested with RsaI) according to Mougel (1997). According to the mtDNA typing, all rabbit populations inhabiting Argentina belonged to the B lineage: rabbits of Tierra del Fuego and Santa Cruz Provinces had the B3 haplotype and those in Neuqué n Province had the B1 haplotype (Table 1). Note that the rabbits of Tierra del Fuego and Santa Cruz (of putative French origin) displayed the B3 haplotype. This haplotype is currently uncommon in France, provinces (Amaya and Bonino 1981). Another possibility is that the initial introductions of rabbits into the Falkland Islands and central Chile were animals from the domestic breeds in existence in France and Spain approximately 250 years ago. To test these two hypotheses about the degree of domestic strain versus wild-European genes in the Argentine populations of the rabbit, we are planning to re-examine our samples using more variable and informative markers at microsatellite loci (Queney et al. 2001). Acknowledgements This paper is dedicated in memoriam to Francisco Barrera (nuestro amigo Paco) deceased in Sierra Nevada in a tragic accident during a rescue practice work. We are grateful to R. Clarke and F. Barrera Sanchez (†) for their assistance in the field and to R.D. Sage, E. Donadio, and anonymous reviewers that helped us to improve the final manuscript. Fieldwork was funded by the Programa de Cooperación Cientı́fica con Iberoamérica (AECI) and the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientı́ficas y Té cnicas (CONICET PIP 937). References Figure 1 Geographic distribution (shading area) of the European rabbit in Argentina. The number indicates the collection sites and these are specified in Table 1. The insert shows (in black) the southwestern part of Argentina under discussion in the text and in the larger section of this Figure. Table 1 Collection sites, sample sizes, and mitochondrial DNA typing of rabbits collected in the different areas of the European rabbit distribution in Argentina. Collection sites Sample sizes Haplotype 1. Estancia Túnel (548579390 S, 688299250 W) 2. Rı́ o Turbio (518359360 S, 728219380 W) 3. Andacollo (378109550 S, 708409310 W) 4. Junı́n de los Andes (398579070 S, 718049130 W) 5. Lago Ñorquinco (398079120 S, 718189110 W) 6. Paso de los Indios (388319430 S, 698249010 W) 7. Sauzal Bonito (388369500 S, 698089000 W) 15 B3 15 B3 6 B1 3 B1 15 B1 3 B1 7 B1 where the B1 haplotype predominates in the commercial and fancy breeds of domesticated rabbits (Queney et al. 2002). These results suggest that the natural populations inhabiting the Patagonia belong to subspecies Oryctolagus cuniculus from which the domestic stocks are derived. The identification as O.c. cuniculus is consistent with the large body size of Argentina wild rabbits (Bonino and Donadio 2008) and the highly variable coat coloration observed in rabbits of Tierra del Fuego and Neuquén Amaya, J. and N. Bonino. 1981. El conejo silvestre europeo (Oryctolagus cuniculus) en Tierra del Fuego. IDIA, Buenos Aires 388: 14–31. Arentsen, P. 1954. Control bioló gico del conejo. Bol. Ganadero, Chile 4: 23–25. Biju-Duval, C., H. Ennafaa, N. Dennebouy, M. Monnerot, F. Mignotte, R. Soriguer, A. El Gaaied, A. El Hili and J.C. Mounolou. 1991. Mitochondrial DNA evolution in Lagomorphs: origin of systematic heteroplasmy and organization of diversity in European rabbits. J. Mol. Evol. 33: 92–102. Bonino, N. and R. Gader. 1986. Expansión del conejo silvestre europeo (Oryctolagus cuniculus) en la Repú blica Argentina y perspectivas futuras. An. Mus. Hist. Nat. Valparaı́so 18: 123– 130. Bonino, N. and R. Soriguer. 2004. Distribució n actual y dispersió n del conejo europeo (Oryctolagus cuniculus) en Mendoza (Argentina). Mastozool. Neotrop. 11: 237–241. Bonino, N. and E. Donadio. 2008. Desarrollo corporal del conejo silvestre europeo (Oryctolagus cuniculus) introducido en Argentina. INTA Bariloche, Comun. Técn. RN Fauna 148: 1–12. Branco, M., N. Ferrand and M. Monnerot. 2000. Phylogeography of the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in the Iberian Peninsula inferred from RFLP analysis of the cytochrome b gene. Heredity 85: 307–317. Chapman, J.A. and J.E.C. Flux. 1990. Rabbits, hares and pikas: status survey and conservation action plan. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. pp. 168. Clarke, R. and J. Amaya. 1986. Presencia del conejo silvestre Oryctolagus cuniculus en la provincia de Santa Cruz. INTA EEA Santa Cruz, Mem. Técn. 2: 89–93. Ennafaa, H., M. Monnerot, A. El Gaaied and J.C. Monolou. 1987. Rabbit mitochondrial DNA: preliminary comparison between some domestic and wild animals. Genet. Sel. Evol. 19: 279– 288. Ferrand, N. and M. Branco. 2006. The evolutionary history of the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus): major patterns of population differentiation and geographic expansion inferred from protein polymorphism. In: (S. Weiss and N. Ferrand, eds) Phylogeography of European Refugia. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. pp. 207–235. Flux, J.E.C. 1994. World distribution. In: (H.V. Thompson and C.M. King, eds) The European rabbits, the history and biology of a successful colonizer. Oxford University Press, Oxford. pp. 8–21. Geraldes, A., C. Roger-Gaillard and N. Ferrand. 2005. High levels of nucleotide diversity in the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) SRY gene. Anim. Genet. 36: 349–351. Goodall, R.N.P. 1979. Tierra del Fuego. Ediciones Shanamaiim, Buenos Aires. pp. 131. Greer, J.K. 1965. Mammals of Malleco Province, Chile. Publs. Mus. Michigan State Univ., Biol. Ser. 3: 49–152. Howard, W.E. and J.N. Amaya. 1975. European rabbits invades western Argentina. J. Wildl. Manage. 39: 757–761. Jaksic, F.M. and J.L. Yañ ez. 1983. Rabbit and fox introductions in Tierra del Fuego: history and assessment of the attempts at biological control of the rabbit infestation. Biol. Conserv. 26: 367–374. Monnerot, M., J.D. Vigne, C. Biju-Duval, D. Casane, C. Callou, C. Hardy, F. Mougel, R. Soriguer, N. Dennebouy and J.C. Mounolou. 1994. Rabbit and man: genetic and historic approach. Genet. Sel. Evol. 26: S167–182. Monnerot, M., O. Loreille, F. Mougel, A.M. Vachot, N. Dennebouy, C. Callou, J.D. Vigne and J.C. Mounolou. 1996. The European rabbit: wild population evolution and domestication. Proc. 6th World Rabbit Congr. 2: 331–334. Mougel, F. 1997. Variations de trois types de marqueurs gé né tiques dans l’evolution de l’espè ce Oryctolagus cuniculus: aspects molé culaires et relations avec la biologie et la structure des populations. Ph.D. thesis, University of Paris-Sud, Paris, France. Queney, G., N. Ferrand, S. Weiss, F. Mougel and M. Monnerot. 2001. Stationary distributions of microsatellite loci between divergent population groups of the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Mol. Biol. Evol. 18: 2169–2178. Queney, G., A.M. Vachot, J.M. Brun, N. Dennebouy, P. Mulsant and M. Monnerot. 2002. Different levels of human intervention in domestic rabbits: effects on genetic diversity. J. Hered. 93: 205–209. Rico, C., U. Kuhnlein and G.J. Fitzgerald. 1992. Male reproductive tactics in the tree spine stickleback: an evaluation by DNA fingerprinting. Mol. Ecol. 1: 79–87. Rogers, P.M., C.P. Arthur and R. Soriguer. 1994. The rabbit in continental Europe. In: (H.V. Thompson and C.M. King, eds) The European rabbit: the history and biology of a successful colonizer. Oxford University Press, Oxford. pp. 22–63. Van der Loo, W., N. Ferrand and R.C. Soriguer. 1991. Estimation of gene diversity at the b locus of the constant region of the immunoglobulin light chain in natural populations of European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in Portugal, Andalusia and on the Azorean Islands. Genetics 127: 789–799. Van der Loo, W., F. Mougel, M.S. Sá nchez, C. Bouton, E. Castien, A. Fonseca, N. Ferrand, R.C. Soriguer and M. Monnerot. 1999. Cytonuclear disequilibria in wild populations of rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus L.) suggest unequal allele turnover rates at the b locus (IGKC1). Immunogenetics 49: 629–643. Wilson, D.E. and D. Reeder. 2005. Mammal species of the world. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. pp. 214. Zunino, S. 1989. Origen y distribución de los conejos en Chile. Bol. Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. (Chile) 316: 8–10.