Postprint_JSFA_2015_V95_P1670.doc

advertisement

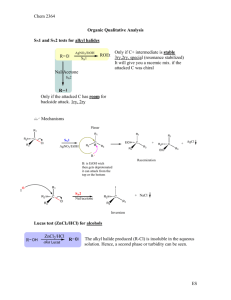

The effect of ZnCl2 on green Spanish-style table olive packaging, a presentation style dependant behaviour J. Bautista-Gallego*, F.N. Arroyo-López, V. Romero-Gil, F. Rodríguez-Gómez & A. Garrido-Fernández. Department of Food Biotechnology. Instituto de la Grasa (CSIC). Avda\ Padre García Tejero, nº 4. 41012, Seville (Spain). *Corresponding author: Joaquín Bautista-Gallego, PhD. Tel: +34 954 692 516. Fax: +34 954 691 262. E-mail address: joaquinbg@ig.csic.es; joaquin.bautistagallego@unito.it; Short title: Effect of ZnCl2 addition on green table olive packaging 1 1 Abstract 2 BACKGROUND: Zinc chloride has been used previously as preservative in directly brined 3 olives with promising results. However, this is the first time that the effects of ZnCl2 addition 4 (0-1 g L-1) on green Spanish-style table olives (Manzanilla cv.) packaging has been studied. 5 RESULTS: The presence of ZnCl2 affected the physicochemical characteristics of the 6 products; presence of the Zn led lower pH values (particularly just after packaging) and 7 titratable and combined acidity values than the control but did not produced clear trends in the 8 colour parameters. No Enterobacteriaceae were found in any of the treatments evaluated. At 9 the highest ZnCl2 concentrations, the lactic acid bacteria were inhibited while, unexpectedly, 10 its presence showed lower effect than potassium sorbate against yeast population. Regardless 11 of the use of potassium sorbate or ZnCl2, the packages had a reduced microbial biodiversity 12 because only Lactobacillus pentosus and Pichia galeiformis were found at the end of the shelf 13 life. With respect to organoleptic characteristics, the presentations containing ZnCl2 were not 14 differentiated from the traditional product. 15 CONCLUSION: Zn chloride was less efficient than potassium sorbate as yeast inhibitor in 16 green Spanish-style olives, showing clear presentation style dependant behaviour for this 17 property. Its presence produced significant changes on chemical parameters but scarcely 18 affected colour or sensory characteristics. 19 20 21 Keywords: Zinc; preservation; shelf life; green Spanish-style olive; table olive packaging. 2 22 1. Introduction 23 The use of olives for human consumption is a well documented tradition in the area 24 around the Mediterranean Basin1 but, currently, table olive processing is found all around the 25 world. In the 2010/2011 season, its production reached 2,440,000 tons. 26 presentation is the so-called green Spanish-style, which accounts for, approximately, 60% of 27 total consumption. These olives are included in the category of treated olives, as defined in 28 the Trade Standard Applying to Table Olives issued by the IOC. 3 Briefly, the process consists 29 of debittering the olives with a diluted sodium hydroxide solution (18-25 g L-1 NaOH) until 30 the alkali reaches 2/3 of the flesh, followed by one or several washing waters to remove the 31 excess alkali. Then, the fruits are covered with brine (100-110 g L-1 NaCl solution) where 32 they typically undergo spontaneous lactic acid fermentation1, although starter cultures can 33 also be used. 4 Finally, the olives are packed according to various commercial presentations. 2 The most popular 34 No zinc (Zn) fortified/preserved green olives are currently available in the market, 35 although this microelement is allowed to be added to foods5,6 and has 18 authorized possible 36 claims in the current European Union legislation. 7 Zn is used in food technology because it 37 forms green colour complexes with chlorophyll derivatives. Thereby, Zn has been applied 38 (followed by heat treatment) to preserve the green colour of pears8 and olives. 9 Moreover, its 39 presence in the continuous alcoholic fermentation reduced the size of flocks, increased the 40 tolerance to alcohol and temperature, decreased the production of glycerol, and accumulated 41 in the yeast dry matter10. Zinc oxide has also shown antimicrobial activity against Listeria 42 monocytogenes, Salmonella enteriditis and Escherichia coli O157:H711, while ZnCl2 has 43 shown a strong inhibitory effect on table olive related yeasts. 44 Aloreña olives, a type of directly brined table olive elaboration, the presence of ZnCl2 led to a 45 marked reduction in Enterobacteriaceae and yeast populations14 and improvement of the 46 nutritional value of the product. 15,16 12,13 In cracked Manzanilla- Furthermore, zinc sulphate and zinc perchlorate 3 47 completely inhibited fungal growth and their ability to produce mycotoxins from toxigenetic 48 strains of Fusarium graminearum, Penicillium citrinum and Aspergillus flavus; the conidia 49 production of all fungi was reduced and hyphae damage was also noticed. 17 Therefore, all 50 these findings suggest the use of Zn as preservative in food industry to control fungal growth. 51 The aim of the present work was to investigate the effect of ZnCl2 as preservative on 52 green Spanish-style table olives packaging. Particularly, the relationships between its 53 presence and the changes in physicochemical, microbiological, and sensory characteristics 54 during shelf life were studied. 55 2. Experimental 56 2.1. Samples and experimental design 57 The experiment was carried out with fully fermented Spanish-style Manzanilla green 58 olives supplied by JOLCA S.A. (Huévar del Aljarafe, Seville, Spain). The experiment 59 consisted of packaging olives in plastic pouches (polyester-polyethylene, 105 mL brine and 60 75 g olives) using the habitual industrial packaging conditions (0.12 g L-1 potassium sorbate, 61 50 g L-1 NaCl, 3.33 g L-1 citric acid, 0.66 g L-1 ascorbic acid and 1.66 g L-1 lactic acid) plus 62 additional treatments in which the presence of potassium sorbate was replaced with 0.25, 63 0.50, 0.75, and 1.00 g L-1 concentrations of ZnCl2; therefore, there were five different 64 treatments in total. The plastic pouches were manually filled with the appropriate brine and 65 closed twice with a thermal sealing at 177ºC for 3 s at the industry. Then, the pouches (a total 66 of 120) were transported and stored at room temperature (20±3 ºC) at the pilot plant of 67 Instituto de la Grasa (CSIC, Seville, Spain). Periodically, two replicate pouches per treatment 68 were removed and analyzed. The packed olives were also subjected to sensory tests at the end 69 of the study (3 months, to mimic the commercial shelf life). 70 2.2. Microbiological analysis 4 71 Brine samples and their decimal dilutions were plated using a Spiral System model 72 dwScientific (Don Whitley Scientific Limited, England) on the media described below. 73 Subsequently, plates were counted using a CounterMat v.3.10 (IUL, Barcelona, Spain) image 74 analysis system, and the results expressed as log10 CFU/mL. Enterobacteriaceae were 75 counted on VRBD (Crystal-violet Neutral-Red bile glucose)-agar (Merck, Darmstadt, 76 Germany), lactic acid bacteria (LAB) on MRS (de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe)-agar (Oxoid 77 LTD., Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) with 0.2 g L-1 sodium azide (Sigma, St. Luis, USA), 78 and yeasts on YM (yeast-malt-peptone-glucose medium)-agar (DifcoTM, Becton and 79 Dickinson Company, Sparks, MD, USA) supplemented with oxytetracycline and gentamicin 80 sulphate as selective agents for yeasts. The plates were incubated at 30 ºC for 48-72 h. 81 Changes in the microbial populations versus time were also assessed by estimating the area 82 under the corresponding growth/decline curves. The areas were calculated by integration 83 using OriginPro 7.5 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, USA). 84 At the end of the study (~3 months), brine samples from the packaging (100 mL) were 85 collected in sterile conditions and plated on the yeast and LAB selective media. Then, a total 86 of 100 isolates, 50 LAB and 50 yeasts (10 for each treatment) were randomly selected and 87 purified by subsequent re-streaking on YM or MRS agar, respectively, and subjected to 88 molecular identification. The different LAB isolates were identified at species level using a 89 multiplex PCR analysis of the recA gene with species-specific primers for Lactobacillus 90 pentosus, Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus paraplantarum, following the protocol 91 described by Torriani et al.18. Yeasts were identified by an RFLP analysis of the 5.8S-ITS 92 rDNA region according to the procedure described by Esteve-Zarzoso et al.19 93 2.3. Physicochemical analyses 94 95 The analyses of brines for pH, NaCl concentration, titratable acidity, and combined acidity were carried out using the standard methods described for table olives. 1 5 96 Olive surface colour analyses were performed using a BYK-Gardner Model 9000 97 Color-view spectrophotometer, equipped with computer software to calculate the CIE 98 coordinates: L* (lightness), a* (negative values indicate green while positive values indicate 99 magenta), and b* (negative values indicate blue and positive values indicate yellow). 100 Interference by stray light was minimized by covering the samples with a box which had a 101 matt black interior. The value for each treatment was the mean of the determinations from 20 102 olives. 103 The colour index (Ci) was calculated according to Sanchez et al.20 Ci 104 2 R560 R590 2 R630 2 R640 3 105 where Rs are for the reflectance values at 560, 590, 630 and 640 nm, respectively. 106 2.5. Sensory analysis 107 Tests were conducted by a panel of 12 members (5 men and 7 women) of experienced 108 judges from the staff of Instituto de la Grasa (CSIC, Seville, Spain). Their age ranged from 25 109 to 55 years and their experience in participating on sensory panels for testing table olives 110 ranged from 4 to 15 years. All judges were familiar with ranking and the A-Not A tests. They 111 were subjected to two sessions during which the objectives and characteristics of the 112 experiment were explained. In addition, they were trained in the specific characteristics of the 113 new products and tests as described below. Two protocols were used: ranking and a modified 114 version of the A-Not A test. 115 In the first case, the control was presented to the judges as the standard and the judges 116 were able to taste the control as much as desired until they felt they had become familiar with 117 its sensory characteristics. Then, the judges were given the control (no ZnCl2) and the 118 products containing from 0.25 to 1.00 g L-1 ZnCl2. The products were presented, in random 119 order, in cups similar to those used in the olive oil tests, and numbered with a combination of 120 letters and numbers. Judges were asked to rank them in order of dissimilarity to the standard 6 121 (1 more similar; 5 less similar). In essence, the test was similar to the first protocol described 122 by Lee et al.21 123 For the A-Not A analysis, the version used by Lee et al.21 of this protocol was used. 124 As in the first protocol, the control was presented to the judges as the standard and the judges 125 were able to taste the control as much as desired until they felt they had become familiar with 126 its sensory characteristics. Then, the control and the four Zn treatments (0.25 - 1.00 g L-1) 127 were given to the judges, using the same methodology described for protocol 1, and were 128 required to report whether the product tasted the same or different from the standard. 129 Responses were given in terms of five categories “same sure”, “same not sure”, “same”, 130 “different not sure”, “different sure”. For the analysis of results, data from all the judges were 131 pooled onto a single response matrix and single R-index was computed. For the calculus, the 132 procedure described in Lee and van Hout22 was used. Significance of the obtained R values 133 was compared with the critical values for two side tests, expressed in percentages of the R- 134 index-50%.23 135 2.6. Statistical data analyses 136 Sigma Plot 12.0 (Systat Software, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Statistica software 137 version 7.0 (Statsoft Inc, Tulsa, USA) were used for data presentation and analysis. 138 3. Results and discussion 139 3.1. Effects of ZnCl2 presence on the physicochemical characteristics 140 Initially, pH values were significantly lower in the Zn containing brines than in the 141 control. This was because the ZnCl2 added behaved as a Lewis acid and, although is order of 142 strength is lower than other usual strong acids like phosphoric, nitric or sulphuric acids24, its 143 presence produces a pH decrease in the fresh brines which is approximately correlated with its 144 concentration. During storage, there was a general tendency for pH to increase, possibly due 145 to equilibrium with the flesh, which lasted for about 10 days, followed by a new decrease 7 146 (Figure 1, upper panel). The treatments containing Zn retained the initial significant lower (as 147 assessed by the no overlapping of their respective confidence intervals) pH values than the 148 control (with sorbate) during about the first 500 h (~20 d) of packaging. Then, the presence of 149 ZnCl2 improves the product safety in such period. This contrasts with the reduced effect that 150 the addition of ZnCl2 in directly brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives had on the initial 151 pH of brines. 14 152 There was later an increase in pH that raised the level to a maximum of 3.55-3.60 at 153 approximately 1800 h (75d) (Figure 1, upper panel), followed by a new decreasing trend 154 which lowered this parameter to 3.50-3.55 at the end of the study (~2500 h or ~100 d). Some 155 of the Zn treatments (particularly those with the highest concentrations) showed also the 156 lowest pH values during this time but the differences were rather reduced. On the contrary, in 157 directly brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives changes with time were reduced. 14 158 At the end of the shelf life, the range of the average pH values among treatments was 159 of only 0.05 units, which probably would be of limited influence on the product stability. 160 Hence, the results have shown that pH did not remain stable during shelf life but 161 experimented some cycles, although with a general tendency to increase with time and a 162 slightly final lowering, leading the presence of Zn to lower pH values than the control en 163 many cases due to it acidic character of this compound. 164 brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives were markedly higher than in this style (4.03 vs. 165 3.5), although they were also similar among treatments. 14 24 The final pH values in directly 166 The concentration of NaCl in the samples had a marked variability during the first 167 1000 h (~42 days) period of packaging (Figure 1, lower panel).These oscillations could be 168 due to the equilibrium phenomenon between brine and flesh because, during the rest of the 169 time, the concentrations were more stable. In directly brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga 8 170 olives there was a marked NaCl initial decrease due to its absorption by the unsalted fresh 171 fruits used. 14 The levels of NaCl in the control treatment were higher than in the products 172 packed with ZnCl2 in most of the sampling points and, particularly, as time progressed; the 173 NaCl concentrations oscillated between 4.8 and 5.2, which is not an excessive range for this 174 product. The final concentrations in NaCl of the Zn added olive samples were significantly 175 lower than in the control. A similar effect of the ZnCl2 presence was observed in directly 176 brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives which final NaCl level was even lower (42 g L-1)14. 177 With respect to titratable acidity (Figure 2, upper panel), the presence of ZnCl2 clearly 178 affected the titratable acidity changes.; however, the acidic character 24 of ZnCl2 was observed 179 only initially and for the highest concentrations but, later, the contents were mostly below that 180 of the control, particularly after 1500 h and, approximately, correlated with concentrations in 181 the fresh brine. In general, many punctual significant differences during the study were 182 observed; although, due to the variability, commenting the overall trend is more convenient. 183 The trends observed in the control, which titratable acidity clearly increased, and that of 184 treatments added with ZnCl2, in which it decreased, particularly during the last part of the 185 study, were quite different. In some cases, the lowest titratable acidity was observed in the 186 treatments containing 0.50 g L-1 ZnCl2, which also had the lowest final titratable acidity 187 (Figure 2, upper panel) while at the end of the study the highest titratable acidity was 188 observed for the control (>6.0 g L-1). This trend in the evolution of the titratable acidity 189 indicates a production of acid by the LAB in the control (with potassium sorbate) and a clear 190 inhibition in the ZnCl2 added treatments. At the end of the study, the average titratable acidity 191 values of the Zn treated olives ranged from 4.8 to 5.2 g L-1, with the lowest value being 192 observed in the olives treated with 10.00 g L-1 ZnCl2; thus, in general, presence of ZnCl2 193 prevented lactic acid production and resulted in a greater stability. On the contrary, the 194 traditional preservative did not prevent LAB activity and led to a titratable acidity in control 9 195 around 10.00 g L-1. The high titratable acidity level is not a safety drawback1 but it is an 196 indication of a deficient stabilization of the product by just sorbate. In this aspect, ZnCl2 had a 197 more convenient behaviour. The trend observed for titratable acidity in this experiment 198 contrasts with that observed in directly brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives in which all 199 treatments increased acidity levels, being observed the highest values in treatments containing 200 0.5 g L-1 and 0.75 g L-1 ZnCl2 (and not in the control); furthermore, the levels in directly 201 brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives were markedly higher and only comparable to the 202 proportion reached in the green Spanish-style control. 14 203 The changes in combined acidity showed a fairly similar trend and had less variability 204 than those observed in pH but with outstanding differences among treatments (Figure 2, lower 205 panel). Initially, this parameter ranged from 0.020 to 0.025 Eq L-1, which is the recommended 206 level for proper packaging1. The acidic character24 of ZnCl2 also affected the levels of 207 combined acidity which was reduced in all treatments with respect to the control. In directly 208 brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives (non lye treated) the initial values were higher 209 (0.045-0.052 Eq L-1)14. However, as time progressed, there was a tendency for combined 210 acidity to increase, especially above 1500 h (~ 63 d). This increase was more relevant for the 211 control and can be related to the production of acid by the LAB. Possibly, part of the lactic 212 acid formed remained as lactate and contributed to increasing the combined acidity, with a 213 more evident effect in the control treatment. On the contrary, all treatments with ZnCl2 added 214 were efficient for mitigating combined acidity changes and led to quite similar values at the 215 end of the study. This increase in combined acidity could possibly be, at least in part, the 216 cause of the pH increase observed in parallel during the same period (Figure 1, upper panel). 217 On the contrary, in directly brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives the combined acidity 218 increase with time was reduced and oscillated between narrow limits (0.060-0.066 EqL-1) 219 without substantial effect of the ZnCl2 addition. 14 10 220 Colour is also an important quality attribute, particularly in the case of transparent 221 packaging materials. Higher values of Ci, specifically developed for green Spanish-style 222 olives20, are associated with better colour appreciations. The variability observed in this 223 parameter during the first period of the study was high and led to only a few significant 224 differences (Figure 3, panel A) while the Ci values were more homogeneous as the study 225 progressed. In any case, in the long run, Zn presence had a reduced effect on Ci. A similar 226 behaviour was also detected by Gallardo-Guerrero et al.9 However, the use of ZnCl2 in fresh 227 directly brined Aloreña de Málaga olives gave rise to a significantly lower Ci than in the 228 control15, indicating a clear different effect of ZnCl2 in both products. 229 High values of L* are related to clearer and more attractive olives. The changes 230 observed in L* (Figure 3, panel B) had smaller variability than most of the previously 231 described parameters. Overall, L* was fairly stable throughout the study although, at the end 232 of the study, two groups were noticed: the first one, with a higher value of L*, consisted of the 233 treatments containing from 0.50 to 1.00 g L-1 ZnCl2, while the second group had a slightly 234 lower L* value and consisted of the control and the treatment with 0.25 g L-1 ZnCl2. Hence, 235 the presence of Zn above a certain proportion may lead to higher final luminance and better, 236 more characteristic, green Spanish-style colour. The trend above described contrast with that 237 observed in directly brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives in which L* values markedly 238 decreased with time and only showed a slight increase at the end of the shelf life. 15 239 The values of a* and b* (Figure 3, panels C and D, respectively) showed high 240 variability and had marked changes from one sampling point to another. Both parameters had 241 at the end of the study slightly higher values in the control than in ZnCl2 added treatments but, 242 in general, the trend with time observed did not show clearly significant changes. In any case, 243 the trends of both parameters were quite different from those observed in directly brined 244 cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives in which a* increased progressively during shelf life while 11 245 b* had an initial increased followed by a decrease fairly similar to that experimented by L* in 246 the same experiment. 15 247 3.2. Effect of ZnCl2 addition on the microbial population 248 No Enterobacteriaceae were found in the plastic pouches of the packed green 249 Spanish-style Manzanilla olives. This is in agreement with the observation reported in studies 250 on the packaging of stored Aloreña cultivar where Enterobacteriaceae were never isolated25 251 and the main cause of its instability was attributed to the growth of yeasts. 26 On the contrary, 252 Enterobacteriaceae were present during approximately half shelf life of fresh directly brined 253 cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives, in spite of the favourable effect of ZnCl2 addition for 254 reducing their populations. 14 255 Regardless of the packaging conditions, in the green Spanish-style Manzanilla olive 256 packages of this study, only LAB and yeast populations were observed in the cover brines 257 (Figure 4). Level of ZnCl2 affected LAB growth/survival, which counts followed a very 258 similar trend in all treatments; however, the curve for 1.00 g L-1 ZnCl2 was below those 259 corresponding to the other treatments in most of the samples (Figure 4, upper panel). Initially, 260 the populations were around 4.5-5.5 log10 CFU mL-1 but a tendency to increase with time was 261 observed, reaching a maximum of 5.5-6.5 log10 CFU mL-1 at ~800 h (~33 d). Later, a new 262 slow general decrease was noticed which led to population levels close to the original ones or 263 below; particularly, the average final LAB population in samples containing 1.00 g L-1 ZnCl2 264 was fairly low, although its differences with respect to some others also containing this salt 265 were not significant due to its high variability. The LAB changes observed in this work are 266 quite different from those described in directly brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives, 267 because in this product, the initial counts were very low (absence of previous lactic acid 268 fermentation) but the evolution resembled more a classical fermentation, in spite of the 12 269 inhibitory effect of the 1.00 g L-1 ZnCl214, than to changes in a stabilized packaging. The 270 different behaviour was possibly caused by the abundance of nutrients in the case of (fresh) 271 Aloreña olives. 272 A convenient approach to studying the overall population changes is the estimation of 273 the area below the growth curve, directly related to the counts of microorganisms throughout 274 the period studied provided this is the same for all curves. Concentrations of 0.25 and 0.75 g 275 L-1 ZnCl2 showed an overall similar behaviour to the control because the confidence limits of 276 their respective areas overlap (Figure 5. upper panel). However, the addition of 1.00 g L-1 277 ZnCl2 had a marked inhibitory effect on LAB population because, in spite of the high 278 variability, the area of this curve was the lowest and significantly different with respect to the 279 other treatments (Figure 5, upper panel). The LAB inhibition by 1.00 g L-1 ZnCl2 in brines 280 had also been detected in fresh directly brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives14, a quite 281 different presentation (non lye treated, cracked, and seasoned) from the green Spanish-style 282 olives studied in this work. The trend observed in the curve of areas in directly brined cracked 283 Aloreña de Málaga olives had a more pronounced peak because the stronger stimulating 284 effects of the intermediate ZnCl2 concentrations. 14 285 The changes in yeast populations were particularly monitored (Figure 4, lower panel). 286 Initially, they were between 4.5-5.0 log10 CFU mL-1 and, with only a couple of sampling 287 exceptions, a clear decrease with time was noticed until about 2000 h (83 d) of packaging. 288 These populations are higher than those initially found in directly brined cracked Aloreña de 289 Málaga olives because the absence of any previous fermentative process in this 290 presentation14. Overall, data from this work show that the inhibitory effect of ZnCl2 on yeasts 291 has been slightly less effective than that of potassium sorbate (control) during a large part of 292 the study. These results contrast with the strong inhibitory effect observed in synthetic 293 medium for ZnCl2. 13 In any case, complete inhibition of the yeast population was not 13 294 achieved in the control either, although its curve was below those of treatments containing 295 ZnCl2 during a marked period of time. In directly brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives, 296 yeasts curves for ZnCl2 treatments were, on the contrary, below the control. 15 297 As in the case of LAB growth, a more general comparison among the yeast 298 populations in the different treatments was made through the representation of the areas under 299 the respective curves (Figure 5, lower panel). There was observed significant effects of ZnCl2 300 levels. Treatments with 0.25 and 1.00 g L-1 showed a great variability, which has led to their 301 confidence limits overlapping. The highest areas were obtained in brines containing 0.25 and 302 0.50 g L-1 ZnCl2 (without significant difference among them), while the presence of 0.75 and 303 1.00 g L-1 ZnCl2 led to lowest areas (higher inhibition) among Zn treatments. On the contrary, 304 the area under the yeast curve corresponding to the control (with potassium sorbate) was 305 significantly lower than any treatment containing ZnCl2. This behaviour indicates a relatively 306 low inhibitory effect of yeast by ZnCl2 with respect to that observed in synthetic culture 307 media where the inhibition was clearly achieved. 13 Furthermore, the present trend contrasts 308 with that observed during the shelf life of directly brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives in 309 which yeasts clearly decreased (the curve of areas was concave) in the presence of ZnCl2, and 310 particularly when the concentration was 0.75 g L-1 ZnCl2. 311 packaging conditions (previous microbial load, salt concentration, type of acid or pH) and 312 olive composition (polyphenols, nutrients, cell wall components or minerals) can also 313 markedly modify the inhibitory action of ZnCl2. 14 Apparently, differences in 314 The identification of the survival microorganisms was considered of interest in order 315 to investigate those LAB and yeasts with the highest resistance to the presence of ZnCl2 or 316 potassium sorbate as preservatives. With this objective, 50 isolates of LAB and 50 isolated of 317 yeasts were subjected to molecular identification. All the isolates from LAB were assigned to 318 the species Lactobacillus pentosus while all yeast strains were identified as Pichia galeiformis 14 319 (data not shown). Therefore, the inter-specific biodiversity in these packages at the end of the 320 shelf life was very limited. These species were also found by Rodríguez Gómez et al.27 during 321 the storage of Hojiblanca and Manzanilla olives intended for the elaboration of ripe olives in 322 an acidic medium. Apparently, the survival of P. galeiformis in these packed olives cannot 323 only be related to the presence of sorbate or ZnCl2, although Bautista-Gallego et al.13 324 described P. galeiformis as well-resistant yeast to ZnCl2 in synthetic medium, with MIC 325 values around 0.15 g L-1, but also to its good adaptation to the table olive environment. 27 326 3.3. Effect of the ZnCl2 addition on the sensory characteristics 327 The ranking test and the modified version of the A-Not A method have the advantage 328 of comparing a series of samples at the same time. 21,28 In the ranking test, the sum of all ranks 329 for the control, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, and 1.00 g L-1 ZnCl2 treatments were 36, 31, 40, 34, and 39, 330 respectively. The critical value for 12 judges and 5 treatments, for p0.05, were 25 (the lowest 331 insignificant rank sum, any treatment) to 47 (the highest insignificant rank sum, any 332 treatment). 28 As the sums of all ranks were within these critical values, it can be deduced that 333 according to this test, there was no significant organoleptic differences among the treatments. 334 The results from the version of the A-Not A ranking test are shown in Table 1. The R- 335 indices for 0.25, 0.50, 0.75 and 1.00 g L-1 with respect to the control were 43.75%, 52.43%, 336 49.56% and 54.17%.22 The critical values for two side tests were 29.07% and 70.93% (12 337 judges and p=0.025). Therefore, using the R-index, all the treatments can be considered 338 similar to the control (the traditional product) from the sensory point of view. 339 It is apparent that the presence of ZnCl2 has in this study a limited effect on the 340 sensory characteristics. However, in directly brined cracked Aloreña de Málaga olives, the 341 addition of this salt affected the preferences of the panellists, particularly in the case of 0.75 g 342 L-1 ZnCl2 (78% preferred this treatment against the control)14and caused products with 15 343 marked different profiles15. The absence of lye treatment of fruits, maturation degree, 344 bitterness levels of both products may be among the causes of the different responses. 345 4. Conclusions 346 The addition of ZnCl2 to the cover brines used for the packaging of fermented green 347 Spanish-style Manzanilla table olives affected the physicochemical characteristics of the 348 traditional product and led to others with specific profiles. The treatment with the highest 349 ZnCl2 in the brine showed a clear inhibitory effect on LAB growth, with L. pentosus as the 350 only LAB species detected at the end of the study. The yeast population decreased 351 progressively along the shelf life in the presence of both potassium sorbate (mainly) and 352 ZnCl2 (less efficiently), with only P. galeiformis survival. This behaviour of Zn chloride was 353 unexpected and specific-dependent for the product; apparently, certain compounds or 354 conditions prevailing in green Spanish style olives may prevent/mitigate the demonstrated Zn 355 inhibitory effect on yeasts. On the contrary, the presence of Zn scarcely affected the sensory 356 profile of the traditional product while the same salt markedly affected non lye, fresh fruits, 357 packed Aloreña olives. Apparently, the effect of ZnCl2 on the organoleptic characteristics of 358 the packed olives is also quite dependant on the presentation style. 359 Acknowledgements 360 This work was supported by the Spanish Government (projects AGL2009-07436/ALI 361 and AGL2010-15494/ALI, partially financed by European regional development funds, 362 ERDF), and Junta de Andalucía (through financial support to group AGR-125). J. Bautista- 363 Gallego and F.N. Arroyo-López wish to thank the CSIC and the Spanish government for their 364 JAE predoctoral fellowship and Ramón y Cajal postdoctoral research contract, respectively. 365 References 16 366 367 368 1 Garrido-Fernández A, Fernández Díez MJ, and Adams RM, Table olives: Production and processing. Chapman & Halls. London. (1997). 2 IOC (International Olive Council), On line reference included in World table olives 369 figures: production (accessed Feb 2013). 370 http://www.internationaloliveoil.org/estaticos/view/132-world-table-olive-igures. 371 372 3 IOC (International Olive Council), Trade Standard Applying to Table Olives. COI/OT/NC Nº 1, December,2004. Madrid, Spain (2004). 373 4 Corsetti A, Perpetuini G, Schirone M, Tofalo R, and Suzzi G, Application of starter 374 cultures to table olive fermentation: an overview on the experimental studies. Frontiers 375 Microbiology 3: article 248, 1-6 (2012). 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 5 Office of Dietary Supplements (National Institute of Health). Dietary Supplement Facts Sheet. Zinc. http://ods.od.nih.gov/ (2011). 6 Regulation (EC) No 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 december 2006. Official Journal of the European Union 30.12.2006 (EN), L404-426. 7 Commission Regulation (EU) nº 432/2012 of 16 may 2012, establishing a list of permitted health claims. Official Journal of the European Union. 25.5.2012 (En). L136-201. 8 Ngo T, and Zhao Y, Formation of zinc-chlorofill derivative complexes in thermally processed green peas (Pyrus communis L.). J Food Sci 72:C397-C404 (2007). 384 9 Gallargo-Guerrero L, Gandul-Rojas B, Moreno-Baquero JM, López-López A, Bautista- 385 Gallego J, and Garrido-Fernández A, Pigment, physicochemical, and microbiological 386 changes related to the freshness of cracked table olives. J Agricult Food Chem 61: pp. 387 3737-3747 (2013). 388 10 Zhao XQ, Xue C, Ge XM, Yuan WJ, Wang JY, and Bai FW, Impact of zinc 389 supplementation on the improvement of ethanol tolerance and yield of self-flocculating 390 yeast in continuous ethanol fermentation. J Biotechnol 139:55-60 (2009). 17 391 11 Jin T, Su D, Zhang H, and Sue H, Antimicrobial efficacy of zinc oxide quantum dots 392 against Listeria monocytogenes, Samonella enteriditis, Samonella enteriditis y 393 Escherichia coli O157:H. J Food Sci 74:M46-M52 (2009). 394 12 Bautista-Gallego J, Arroyo-López FN, Garrido-Fernández A, García-García P, López- 395 López A, and Rodríguez-Gómez F, Composiciones conservantes de aceitunas con 396 actividad antifúngica. Solicitud P201030491. Ref. ES1641.387 (2010). 397 13 Bautista Gallego J, Romero Gil V, Garrido Fernández A, and Arroyo López FN, Modeling 398 the inhibitory effect of zinc chloride on table olive related yeasts. Food Control 23:499- 399 505 (2012). 400 14 Bautista Gallego J, Arroyo López FN, Romero Gil V, Rodríguez Gómez F, and Garrido 401 Fernández A, Evaluating the effect on Zn chloride as a preservative in cracked table olive 402 packing. J Food Protect 74:2169-2176 (2011). 403 15 Bautista Gallego J, Moreno Baquero JM, Garrido Fernández A, and López López A, 404 Development of a novel Zn fortified table olive product. LWT-Food Sci Technol 50:264- 405 271 (2013a). 406 16 Bautista Gallego J, Rantsiou K, Garrido Fernández A, Cocolin L, and Arroyo López F.N. 407 Salt reduction in vegetable fermentation: reality or desire? J Food Sci 78:R1095-R1100 408 (2013b). 409 410 17 Savi GD, Bortoluzzi AJ, and Scussel VM, Antifungal properties of Zinc-compounds against toxigenic fungi and mycotoxin. Int J Food Sci Technol 48:1834-1840 (2013). 411 18 Torriani S, Felis GE, and Dellaglio F, Differentiation of Lactobacillus plantarum, L. 412 pentosus, and L. paraplantarum by recA gene sequence analysis and multiplex PCR assay 413 with recA gene-derived primers. Appl Environm Microbiol 67:3450-3454 (2001). 18 414 19 Esteve-Zarzoso B, Belloch C, Uruburu F, and Querol A, Identification of yeasts by RFLP 415 analysis of the 5.8S rRNA gene and the two ribosomal internal transcribed spacers. Int J 416 Syst Bacteriol 49:329-337 (1999). 417 418 20 Sánchez AH, Rejano L, and Montaño A, Determinación del color en las aceitunas verdes aderezadas de la variedad Manzanilla. Grasas Aceites 36:258-261 (1985). 419 21 Lee HS, van Hout D, and O’Mahoy M, Sensory difference tests for margarine: A 420 comparison of R-Indices derived from ranking and A-Not A methods considering 421 response bias and cognitive strategies. Food Qual Prefer 18:675-680 (2007). 422 423 424 425 426 427 22 Lee H.S, and van Hout D, Quantification of sensory and food quality: The R-index analysis. J Food Sci 74:R57-R64 (2009). 23 Bi J, and O’Mahoney M, Updated and extended table for testing the significant of the Rindex. J Sens Stud 22:713-720 (2007). 24 McDaniel, D.H. Acidity of Zn chloride solutions. Inorganic Chemistry 18: 1412-1412 (1978). 428 25 Arroyo-López FN, Storage and packing of Manzanilla-Aloreña. Design of mathematical 429 models to express the growth and inhibition of the microbial population. PhD Thesis. 430 University of Seville. Spain (2007). 431 26 Arroyo-López FN, Bautista-Gallego J, Segovia Bravo KA, García García P, Durán 432 Quintana MC, Romero C, Rodríguez Gómez F, and Garrido-Fernández A, Instability 433 profile of fresh packed “seasoned” Manzanilla-Aloreña table olives. LWT-Food Sci 434 Technol 42:1629-1639 (2009). 435 27 Rodríguez-Gómez F, Arroyo López FN, López López A, Bautista Gallego J, and Garrido 436 Fernández 437 fermentation/storage phase of ripe olive processing. Food Microbiol 27:604-612. (2010). A, Lipolytic activity of the 19 yeast species associated with the 438 439 28 Jellinek G, Ranking tests, in Sensory evaluation of foods. VCH, Weinheim, Federal Republic of Germany (1985). 440 20 441 442 Figure 1. Effect of ZnCl2 on pH (upper panel) and chloride concentration (lower panel) in 443 brines of packed “Manzanilla” during shelf life. For each sample point, confidence limits that 444 do not overlap indicate significant differences at p <0.05. Symbols and treatments 445 correspondence: 446 , Control; , 0.25 g L-1; , 1.00 g L-1 of ZnCl2. 447 448 449 450 451 452 453 21 , 0.50 g L-1; , 0.75 g L-1; 454 455 456 457 458 459 Figure 2. Effect of ZnCl2 on the titratable acidity (upper panel) and combined acidity (lower 460 panel) in brines of packed “Manzanilla” during shelf life. For each sample point, confidence 461 limits that do not overlap indicate significant differences at p <0.05. Symbols and treatments 462 correspondence: 463 , Control; , 0.25 g L-1; , 1.00 g L-1 of ZnCl2. 464 465 466 22 , 0.50 g L-1; , 0.75 g L-1; 467 468 469 470 471 472 Figure 3. Effect of ZnCl2 on colour index (panel A), L* (panel B), a* (panel C) and b* (panel 473 D) according to treatments in packed “Manzanilla” olives. For each sample point, confidence 474 limits that do not overlap indicate significant differences at p <0.05. Symbols and treatments 475 correspondence: 476 , Control; , 0.25 g L-1; , 1.00 g L-1 of ZnCl2. 477 478 479 480 23 , 0.50 g L-1; , 0.75 g L-1; 481 482 483 484 485 Figure 4. Effect of ZnCl2 on the microbial populations in the brine of packed "Manzanilla” 486 olives during shelf life. Changes in lactic acid bacteria (upper panel) and yeasts (lower panel) 487 vs. time, according to treatments. For each sample point, confidence limits that do not overlap 488 indicate significant differences at p <0.05. Symbols and treatments correspondence: 489 Control; 490 ZnCl2. , 0.25 g L-1; , 0.50 g L-1; 491 492 493 494 495 496 24 , 0.75 g L-1; , , 1.00 g L-1 of 497 498 499 500 501 Figure 5. Effect of ZnCl2 on the areas under lactic acid bacteria (upper panel) and yeasts 502 (lower panel) curves vs. time, according to treatments (concentrations of ZnCl2 expressed as g 503 L-1). For each sample point, confidence limits that do not overlap indicate significant 504 differences at p <0.05. 25 Table 1. Results of the response matrix for the computation of the R-index when the five products (including the control as reference) were tested using a similarity ranking to a reference product. Different Different Different Same Same Total sure unsure unsure sure * 12 1 2 2 5 2 0.25 12 1 4 6 0 1 0.50* 12 4 0 1 4 3 0.75* 12 3 3 2 2 2 1.00* 12 3 3 1 1 4 Control -1 *Note: ZnCl2 concentrations in g L . Treatments 26