Anatomical System Pathology Example 2

advertisement

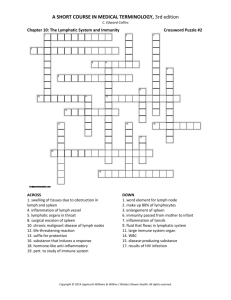

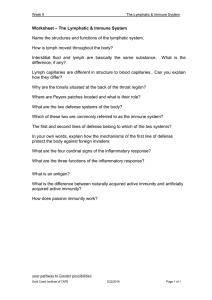

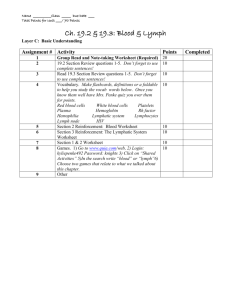

Elephantiasis Diag n o s t i c Image C o mpendium COMPILED BY JULIA GUNDLING 0187666 B I O L 2 1 8 H U M A N A N AT O M Y FA L L 2 0 1 0 Elephantiasis Diag n o s t i c Image C o mpendium • The following collection of images present a pathological condition called lymphatic filariasis, more commonly known as elephantiasis. • The intention for this presentation is to outline an example of what can happen when the lymphatic system is unable to function normally, to provide information about this specific disease (lymphatic filariasis), and to highlight current methods of treatment and prevention. • First, we will review the lymphatic system, outlining its structures and functions under normal conditions. This is followed by an introduction to what happens within this system during a pathological stress. • Then proceeds a discussion of the disease itself, including causes, symptoms, diagnoses, etc. Each of these topics is illustrated using diagnostic images and diagrams. • Finally, this report concludes with a review of current treatments and prevention techniques employed to deal with this tragic condition. Overview of the Lymphatic System Thelymphatic systemis a network of tissues and organsarrangedthroughoutthe humanbody.It consists of lymph vessels, lymph nodesand lymph fluid. Lymphvessels carrylymph fluid throughoutthe body,analogous to howarteriesand veins transport blood. Scatteredthroughoutthesevessels are lymph nodes,which aresmall oval lymphoidorganswhere blood vessels and nervesattach. Nodes filter and purify lymph, removingand digestingdebris, antigens and pathogensas lymphflows past. Lymphnodesare distributedthroughoutthe bodyin a general pattern. Lymphfluid is an interstitial fluid that carries white blood cells, which defendthe bodyagainst germs. It is composedprimarily of lymphocytes(accounting for 99%of the cells in lymph). The rest are phagocytic macrophages, eosinophils and neutrophils. Lymph is normallyclear and coagulable, passing through intercellular spaceswithin tissues,enteringcirculationthroughducts, filtering throughporesin capillary walls, and travelling throughthe lymph nodesbeforeeventually mixing back into the blood. Lymph picks up bacteria and foreignsubstances,delivering themto the lymph nodeswhere they arethen destroyed. Lymph not only transports cells, but also bathesthe cells with water and nutrients. The spleen carries a number of lymphnodes that fight infection. The thymus and bone marrowproducelymph cells. IMAGE 1: Lymph nodes are distributed throughout the body in a general pattern Thelymphatic system is the body’s primary mechanism of defense.It clears away infectionand keepsbodyfluids in balance. It deposits excess fluids and proteinsback into the bloodstream. IMAGE 2: Lymph vessels carry fluid throughout the body analogous to how arteries and veins transport blood. Here, a lymph vessel (yellow) is pictured alongside blood vessels. If the lymphatic systemdoes not functionproperly, fluids build up within tissues.This results in lymphedema,an accumulationof lymphfluid that causesswelling. Lymphedemaresults frominfection, obstruction of the lymphaticsystem,cancer, scar tissue(fromradiation therapyor surgical removal of lymph nodes) and from inherited conditions (in which the structural componentsof the lymphatic systemare either abnormal or absent). Elephantiasis is a severe expressionof lymphedema. IMAGE 3: Anatomy of a Lymph Node What is Elephantiasis? IMAGE 4 Lymphatic filariasis (elephantiasis) is a chronic disease characterized by abnormal enlargement of any part of the body due to obstruction of the lymphatic channels in that area. The most common cause of this disease is infestation by parasitic, microscopic thread-like worms of several different genera, including Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi and B. timori. The adult worms live only in the human lymph system, where they obstruct the normal flow and function of lymph fluid causing inflammation, fibrosis and edema. Conditions can be greatly worsened by secondary bacterial and fungal infections that the impaired lymphatic system is no longer able to combat. Female mosquitoes are the vector for this disease, carrying the parasite from one individual to another. When an infected mosquito bites a human, parasitic worm larvae are injected into the bloodstream where they reproduce and spread into the lymph. People with the disease suffer from severe lymphedema, characterized by the thickening of the skin and underlying tissues especially in the limbs. In men, swelling often occurs in the scrotum, a condition called hyrocele, which in some cases can be quite severe. Elephantiasis may also occur in the absence of parasitic infection, referred to as “nonfilarial elephantiasis” or “podoconiosis.” IMAGE 4 shows the life cycle of Brugia malayi in the mosquito vector and then in the human host through both the infective and diagnostic stages. IMAGE 5 shows how the parasite is passed from vector to host. IMAGE 6 is a photomicrograph of an adult Brugia malayi worm at the diagnostic (human host) stage. IMAGE 7 shows a cluster of Brugia malayi worms as they multiply within the lymphatic system. IMAGE 6 IMAGE 5 IMAGE 7 IMAGE Pathogenesis IMAGE 8: Histological presentation of lymphatic fibrosis (thickening of the dermis and subcutaneous layers that results from excessive production of fibrous connective tissues) IMAGE 9: Fibrosis showing affected lymph vessels. Lymphatic filariasis is a complex interaction between several factors . . . the worm, symbiotic Wolbachia bacteria within the worm, the host’s immune response and any number of other opportunistic infections that arise to take advantage of the impaired immune defenses of an obstructed lymphatic system. As the parasites accumulate in lymph vessels, they can restrict the circulation of lymph fluid and cause fluid to pool in surrounding tissues. The accumulation of protein-rich lymph fluid in the affected body region is thought to induce fibroblast proliferation and impair local immune response. Unchecked proliferation of fibroblasts results in excessive production of fibrous connective tissue, resulting in a thickening of the dermis and subcutaneous tissues. Diminished immune response creates a greater possibility of lymphangitis, a recurrent inflammation which leads to further fibrosis in the dermis and the lymphatic system. As the affected area becomes increasingly thickened and fibrosed, lymphedema worsens and the condition progresses. Lymphedema of the tissues in an affected area appears as papules, lesions, abnormal enlargements and woody fibrosis. IMAGE 10: Lymphangitis; inflammation of lymph tissues IMAGES 12 and 13>> show abnormal enlargement of limbs and tissues as a result of lymphedema IMAGE 11: Early signs of lymphangitis; external signs of lymph inflammation Clinical Presentation Symptoms of elephantiasis often do not present until years after infection. Symptoms of acute and chronic infection include: • • • • • • • Fever Pain in and near the testicles Enlarged lymph nodes, particularly in the groin region Massively swollen legs, torso, genitalia and breasts White urinary discharge Swollen liver Swollen spleen Elephantiasis is a progressive disease. Without intervention deformity and disability are ongoing and debilitating. The following IMAGES 14-19 all show the various forms and symptoms of elephantiasis. Prevalence and Demographics According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, lymphatic filariasis is globally considered to be a “Neglected Tropical Disease,” a grouping of infectious diseases known to cause tremendous suffering. These diseases are characterized by their debilitating, disfiguring and sometimes deadly effects. In fact, lymphatic filariasis is a leading cause of permanent disability worldwide. Elephantiasis is common in tropical regions where the mosquito vector thrives and where preventive resources are scarce, such as in parts of Africa, India and on tropical islands. Nonparasitic forms of elephantiasis also show wide dispersion and are thought to caused by persistent contact with irritant soils (particularly red alkali clays associated with volcanic activity). High prevalence has been documented in Uganda, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Kenya, Burundi, Sudan, Tanzania, Egypt and Cameroon. Individuals with elephantiasis are frequently disabled to the point of being unable to work. This affects families and communities. Women and men disfigured by the disease are frequently shunned. Endemic occurrence is common, as more than one individual within the same community may be affected by the mosquito vector. IMAGE 20: This map shows the global distribution of lymphatic filariasis. Bright red coloration refers to those countries where the disease is endemic. Pale green identifies those countries where lymphatic filariasis is not endemic, and pink highlights those regions where it is uncertain whether or not prevalence e of the disease is endemic. Treatment Without intervention, lymphatic filariasis causes progressive deformity and usually results in death due to related complications. Recovery is possible, but any elephantiasis that develops in the course of the disease is irreversible. The disease can be treated with medication, but this is not always straightforward as the medications are most effective when administered soon after infection and elephantiasis is difficult to detect early. Also, some of the medications have toxic side effects. Drug treatments include: IMAGE 21: A diagnostic CT scan of lymphedema, used to determine surgical procedure. • ivermectin- an antifilarial drug •diethylcarbamazine- kills or impairs the reproduction of adult worms •albendazole- currently used in a program of mass drug administration undertaken by the World Health Organization in 1999 in an attempt to IMAGE 22: Distribution of the drug albendazole, currently used to treat lymphatic filariasis eradicate the worms Clinical trials of the common antibiotic doxycycline conducted by the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine have shown that it is an almost completely effective treatment. The antibiotic kills the symbiotic Wolbachia bacteria that live inside the worms which then cause the worms to die too. Further research on this treatment is being performed. Surgical treatment can be helpful for hydrocele and related issues in the groin region, but it is typically ineffective at correcting elephantiasis in other affected areas such as the limbs. Another form of treatment involves thorough cleaning of the affected areas. These rigorous daily cleaning routines have been shown to reduce and ease some symptoms of the disease, helping to reduce disfigurement and suffering. IMAGE 23: A sonographic assessment of the effects of albendazole and diethlycarbamazine on adult filarial worms and adjacent host tissues; this subject had five filarial worm nests prior to treatment. A and B show hydroceles present three months after treatment, and C shows hydroceles still present at 24 months after treatment. So, it is seen that the drugs used to treat lymphatic filariasis are effective at killing the worms but not at removing the damage done to tissues as a result of the disease. Prevention . . . Controlling mosquito population is fundamental in reducing the incidence of lymphatic filariasis. Prevention of non-filarial elephantiasis consist of simple routines such as wearing shows (to avoid contact with irritant soil), hygienic acts of washing the legs and feet with soap and water, daily soaking in antiseptic solution, and application of specific ointments. Outlook . . . Treatments for lymphatic filariasis depend on the geopgraphic location of the endemic area, a strategy called “geo-targetting” which is part of a larger goal (expressed by the WHO) to eliminate the disease by 2020. Efforts thus far have been successful in reducing the occurrence of lymphatic filariasis. This has not been as true for non-filaritic elephantiasis (podoconiosis) however, which has not yet been added to the list of Neglected Tropical Diseases. Greater international awareness is needed before complete elimination is possible. Research . . . In 2007, a team of genetic researchers funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH), mapped the genome of Brugia malayi. Understanding the genetic content of these worms may lead to the development of new drugs and/or a potential vaccine. IMAGE 24 IMAGE 23 IMAGE 23: Hygiene and the simple act of washing of the legs and feet can help prevent non-filarial elephantiasis in regions where potentially infected soil is present. IMAGE 24: A chart compiled by the WHO showing those populations most at risk of infection and thus targeted by the diseaseelimination program. IMAGE 25: Brugia malayi, whose genome was mapped by researchers in 2007. This effort may lead to further developments and a potential vaccine to prevent lymphatic filariasis. IMAGE 25 Summary and Conclusion o In this compendium we examined the various structures and functions of the lymphatic system. This included: o structural highlights of lymph vessels, lymph nodes and lymph fluid o immune and defense functions of the lymphatic system under normal conditions o what may result when the lymphatic system is no longer able to function normally: lymphedema o Then we examined the specific condition called lymphatic filariasis, or elephantiasis o The disease has filarial mosquito vector-borne origins and non-filarial origins o The most common form occurs when parasitic worms such as Brugia malayi invade and obstruct the lymphatic system o This leads to fibrosis, lymphangitis and lymphedema o Symptoms include abnormal enlargement of limbs and tissues, pain and progressive disability o The disease is incurable, though some treatments may help to control the symptoms and prevent further suffering. A common drug used to combat elephantiasis is albendazole, which is currently being used by the WHO in a global attempt to eradicate the (filarial) disease. This treatment is effective at killing the disease-causing parasites, but not at reducing/removing abnormal and pathologically affected tissues. With the recent mapping of the parasitic worm’s genome, there is hope for a future vaccine. o This diagnostic image compendium would be complimented by further research and a secondary compendium that would do any of the following: ohistological and pathological comparisons of elephantiasis of filarial vs. non-filarial origin o analyze the results of current drugs and treatment methods and compare effectiveness o examine varying forms and variations of the disease in different endemic regions o o o introduce current research/development addressing elephantiasis and explore the possibilities of a future vaccine outline the WHO’s elephantiasis elimination program . . . will lymphatic filariasis be eliminated by the stated goal of 2020? The World Health Organization (WHO) website as well as that of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were helpful resources in the formation of this compendium because they provide current, dependable and scientifically-based information. The Napa Valley College Library website’s EBSCO document search was also helpful in providing peer-reviewed articles and journal documents written by medical specialists, universities and research organizations. These presented much stronger and more professional references than what may have been pulled from a simple internet search. References -Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis World Health Organization http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2002/WHO_CDS_CPE_CEE_2002.28.pdf -Parasites-Lymphatic Filariasis Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lymphaticfilariasis/ -Elephatiasis Nostras Verrucosa Krisanne Sisto and Amor Khachemoune American Journal of Clinical Dermatology, 2008; 9 (3) -Lymphatic Filariasis USAID’s Neglected Tropical Disease Program http://www.neglecteddiseases.gov/target_diseases/lymphatic_fillriasis/cycle.html -Elephantiasis Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition Database: Middle Search Plus: http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?hid=18&sid=8d5f28fc-405f-4404-bc413e50b9ce92c9%40sessionmgr14&vid=4&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=mih&AN=39004700 -Elephantiasis of non-filarial origin in the highlands of north–western Cameroon Wanji, Tendongfor, Esum, Che, Mand, Tanga Mbi, Enyong and Hoerauf Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology, Vol. 102, No. 6, 529–540 (2008) -Progress report on mass drug administration in 2009 World Health Organization Weekly epidemiological record; 17 SEPTEMBER 2010, 85th YEAR; No. 38, 2010, 85, 365–372; http://www.who.int/wer -The Function of Human Lymph Glands SteadyHealth http://www.steadyhealth.com/articles/The_function_of_human_lymph_glands_a38.html\ -Elephantiasis WebMD http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/elephantiasis Image Gallery http://66.244.141.33/IMG/jpg/01_glild_nodular_lip_03_8.jpg http://www.nature.com/ki/journal/v75/n8/images/ki200980i1.jpg http://www.cloudninemarketing.com/healthhealersnews/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/Bild_Medizin_lymphaticsystem.jpg http://a248.e.akamai.net/7/248/430/20080327144034/www.mercksource.com/ppdocs/us/common/dorlands/do rland/images/nodus_n.%20lymphoideus%281%29.jpg http://www.mylymphedema.com/images/lym_system2.gif http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/ http://farm2.static.flickr.com/1342/1204668153_c68d88f343.jpg https://apps.who.int/ctd/filariasis/images/LF_MAP_small.jpg http://priory.com/med/respfail_files/image006.gif http://www2.bc.cc.ca.us/bio16/images/21-02_Lymphangitis_1.jpg http://www.sciencedaily.com/images/2007/09/070920145417-large.jpg http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/vol298/issue15/images/medium/jwm70008fa.jpg http://www.reuters.com/resources/r/?m=02&d=20070920&t=2&i=1797599&w=460&fh=&fw=&ll=&pl=&r=200709-20T221117Z_01_N20421099_RTRUKOP_0_PICTURE0 http://www.searo.who.int/Image/oth_Health_Situation_figure49.gif http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/images/lymphaticfilariasis/mosquitoes/aaegypti.jpg http://sarcomahelp.org/learning_center/figures/ang7.jpg http://www.ajtmh.org/content/vol71/issue4/images/large/471f6_1o.jpeg http://www.biog1105-1106.org/demos/105/unit7/media/elephantiasis.jpg http://www.bio.davidson.edu/courses/immunology/Students/spring2006/Heeren/eleph_clip_image004.jpg http://29.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_l9op7sHxBr1qciwy5o1_400.jpg http://www.scienceclarified.com/everyday/images/scet_03_img0278.jpg http://www.abc.net.au/reslib/200801/r215078_834344.jpg http://endtheneglect.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/LEPRA1.jpg