Oil and Governance - Depletion Policy

advertisement

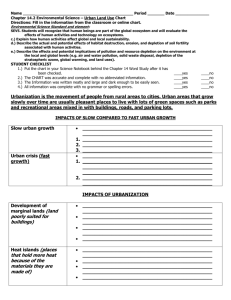

OIL AND GOVERNANCE Depletion Policy Some authors (Stevens 2008) say that measuring the performance of NOCs is difficult and controversial. These are a great number of metrics conventionally used. One common features is that many depend upon reserves or production levels This use of reserves and production data is reinforces for NOCs because they often exhibit extremely poor transparency of financial data commonly available for IOCs. 1 Two Fundamental Problems • Accuracy of the reserve figures – Triggered by OPEC first in 1987- how to allocate production quotas. Continues to be a challenge in the absence of any independent evaluation of reserves there remains doubt over their accuracy. Thus using them as a metric of the performance for a NOC is dubious. 2 Two Fundamental Problems • The second problem using reserve and production levels as a performance metric concerns depletion policies. The figures for reserve and production emerge as the result of depletion policy 1-4 “Low” figures or reserves of production growth could be a symptom of poor performance by the NOC or could be a deliberate depletion policy by the reserve owner (NOC) 3 • Depletion Policy- decisions in deciding how quickly or slowly to develop the depletion amount. – Explore commercial find • Do not develop/ or develop • Do not produce/ or produce • Spend/save domestically or invest abroad • Key choice is because oil is an exhaustible resource Barrel produced today cannot be produced tomorrow • Barrel not produced today will earn a rate of return. See schedule/table 3 1-6 Existence of NOCs Depletion became an issue because IOCs were operating under “oil style concession agreements” giving them virtually total management freedom. Effectively IOCs set depletion rate of most exporters. Ended with the end of the nationalization of the operating J-Vs in the early 1970’s 4 • Depletion lies in the hands of the government. After 1st oil shock of 1978/79, growing tendency to “leave the oil in the ground” • Driven by number of factors – Wide spread belief that the oil process would rise in the future – Some countries had real fears assets were exposed to political risk – Practical problem overseas assets might be exposed to political risk between their gov’t and US gov’t – Gov’ts simply lacked competence and capacity to manage hrydocarbon reserves following forced withdrawal of IOCs. – Capacity expansion was simply not a realistic answer. 5 • Second oil shock 1978-81 –oil ___ would carry on rising forever –thus why increase production capacity • The inexorable rise in excess capacity caused OPEC to cut back production and were forced to defend prices. • In 12 years following 1978, non-OPEC production grew by 12.6 million bpd 6 • 1990’s, attitudes began to change – Lower prices created serious macroeconomic problem – OPEC quotas were open upstream to IOCs – By 1998 only Sadia Arabia and Mexico were off limits to IOC investment • Following oil collapse in 1998, changed again – Related to depletion policies dependency on were oil sector dominated by private sector or a NOC – “Peak Oil” ever rising prices thus reserves were increasingly valuable (oil in the ground) – Plus cost of service companies made production and exploration became increasingly expensive 7 • The principal- agent view of the oil sector make young post-graduate students returning home that NOCs by their very nature are high cost, inefficient, and prone to indulging in rent seeking. In many cases, NOCs were starved of funds to pursue any depletion policy that requires any increased capacity and production levels 8 • Therefor we must be cautious about performance from reserves and production data. Growth is not always a sign of improved performance nor are declining numbers more than a reflection of inefficiency, may simply reflect government performance in a dynamic oil market. (Saudi 200- 207) • Page 209 quotes a book by Simmons that Saudi reserves were grossly over stable 9 • Statoil (ps99)- 640 10 Moving Forward • Question- how rapidly the company can evolve into a global player while keeping domestic production high. This means growing reserves through improved domestic exploration as well as through both strategic M&A and organic exploration abroad. • Statoil must find the right ways to meld technological leadership with hard-headed strategic decision making and efficient execution. 11 • Recent years purchase does not depend on any privileged position in closed markets such as – Deepwater US – Oil sand in Canada – Shale gas in US • An explanation might be Algeria and the Shtokman project and Total and Gazprom. 12 Reserves Replacement and Cost Structure for Selected NOCs (2004-2007) Petrobras StatoilHydro CNOOC Petronas IOCs Domestic 109% 66% 131% 150% 73% International -61% 107% 684% 110% 73% Domestic $8.87 $15.40 $10.93 NA $15.62 International $23.60 $56.32 $18.32 NA $19.51 RRR % 89% 73% 191% 119% 68% RRC $/BOE $11.51 $25.06 $14.78 $2.50 $17.23 Reserve Replacement Rate %(BOE) Reserve Replacement Cost (RRC) $/BOE Combined Domestic/International 1 - 16