SteebCapstone

advertisement

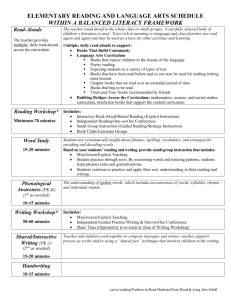

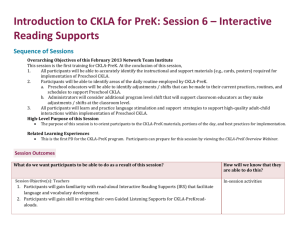

Running Head: INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS Interactive Read-Alouds and Cross-Curricular Learning: Bridging an Implementation Gap in Today’s Classrooms Caitlin Steeb Vanderbilt University Capstone Essay 1 INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 2 Abstract Interactive read-alouds are an integral part of any elementary classroom literacy block, with research touting their significance in the development of students’ love of reading and their benefits in building students’ language skills, vocabulary, comprehension, and ability to think deeply about texts in a collaborative setting. Despite the multitude of benefits, interactive readalouds are being implemented less frequently and without best practices due to the current state of education, in which time and data are overpowering teachers’ ability to bring authentic, interactive read-alouds into the classroom. This Capstone Essay will explore the disconnect between best-practice implementation of interactive read-alouds and their current presentation in today’s classrooms. Keeping in mind the present need for efficiency, recommendations for cross-curricular read-alouds, particularly of science texts, will illustrate a means of providing students with the neglected content of science in an engaging and multi-functional medium. These interactive read-alouds of science texts will allow students to access abstract, scientific content in a way that improves their content knowledge, vocabulary, and problem-solving abilities. This Capstone Essay will show how melding interactive read-alouds with science content ensures that students are receiving a comprehensive knowledge base of multiple subjects while developing their overall collaboration and critical thinking abilities. INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 3 Introduction While on the outset seen as just a “simple and pleasurable activity,” the classroom readaloud, when implemented effectively, is a planned and purposeful strategy that positively affects children’s academic and literacy success (Dorion, 1994; Kindle, 2004). Specifically, interactive read-alouds, in which students are actively engaged with a text—making connections, problemsolving, and asking and answering questions—with the support of their peers and teacher, have numerous benefits (Heisey & Kucan, 2010; Kindle, 2009; Fisher et al., 2004) and have been recommended as a valid instructional practice by the International Reading Association (Kindle, 2009) and National Association for the Education of Young Children (Kindle, 2009). Across the literature, I’ve found the two overarching benefits of read-alouds to be that they build students’ early literacy skills as well as their motivation in and engagement with reading (Fox, 2013; Kindle, 2009; Fisher et al., 2004). Children’s oral language skills, vocabulary, print awareness, and knowledge base of various experiences are built through classroom read-alouds (Fox, 2013; Kindle, 2009; McGee & Schickedanz, 2007; Fisher et al., 2004). These skills and awareness are cultivated due to the nature of the interactive read-aloud experience, in that it excites students about books and information through listening and interaction, motivating them to read and explore themselves (Fox, 2013; Kindle, 2009; Fisher et al., 2004). While the current research points to the strengths of using interactive read-alouds in the classroom to foster deep learning of content, literacy skills, and strategy usage, as well as to develop cooperative learning and shared understandings, there is a great barrier to its implementation. This restriction is the current educational context, in which structured, skillbased reading programs and lack of time reign. My synthesis of research and classroom experiences, have revealed first-hand how these limitations are negatively affecting teachers’ INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 4 implementation of read-alouds in their classroom, and subsequently, their students’ learning (Baker et al., 2013; Kindle, 2009; Lane & Wright, 2007; Barber, Nagy-Catz, & Arya, 2006; Copenhaver, 2001). Given this current state of education and my desire, as a teacher, to implement interactive read-alouds due to the abundance of research proving its significance and beneficial effects, the purpose of this Capstone Essay is to prove the benefits of implementing interactive read-alouds and to provide recommendations on how teachers can remedy today’s classroom challenges by using interactive read-alouds for cross-curricular integration, particularly with science. In the following sections, I present support for interactive read-alouds, rather than teacher-initiate-evaluate read-alouds, and their roles in the context of today’s classroom. A synthesis of the research on interactive read-alouds’ benefits and constraints, and best practices will follow. Then, I will use this knowledge to make sound recommendations for cross-curricular interactive read-alouds, using science as an example, to the benefit of all learners. Interactive versus Teacher’s Monologue The structure of a classroom read-aloud, particularly the conversations and discussions initiated by the teacher and students before, during, and after a read-aloud, is vastly inconsistent (Oyler & Barry, 1996). This variability, due to classroom limitations and a lack of knowledge of sound implementation practices, impacts the effectiveness of classroom read-alouds (Baker et al., 2013; Copenhaver, 2001). This section will provide a reference for two read-aloud styles and tout the greater effectiveness of interactive read-alouds over teacher’s monologue. Benefits of read-alouds are compounded and most attainable when teachers perform interactive read-alouds as, “merely reading books aloud is not sufficient for accelerating children’s oral vocabulary development and listening comprehension. Instead, the way books INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 5 are shared with children matters” (McGee & Schickedanz, 2007, p. 742). Interactive read-alouds engage students throughout the reading process, creating a community of learners amongst the teacher, student, and their classmates as they learn beyond the text presented on the page (Varelas & Pappas, 2006; Barrentine, 1996). These interactions and personalized engagement inherent in interactive read-alouds are representative of Louise Rosenblatt’s transactional theory of reading, in which students use their unique schema to create interpretations of texts (Mills, Stephens, O’Keefe, & Waugh, 2004). Students are engaged in constant, spontaneous dialogue, providing their insights, interpretations, connections, and questions about the text, upon which the teacher provides extensions and supports (Baker et al., 2013; Varelas & Pappas, 2006; Barrentine, 1996). Teachers facilitate students’ continuous thinking and awareness of the learning process by demonstrating and modeling what good readers do, including providing explicit instruction and strategy use (Morrison & Wlodarczyk, 2009; Barrentine, 1996). An interactive read-aloud is in contrast to a teacher-centered approach, known as initiateresponse-evaluate, IRE, or the teacher’s monologue (Varelas & Pappas, 2006; Copenhaver, 2001). While IRE is “not by default an inappropriate pedagogical practice,” it is limited in the type of engagement and interactions students can have and in reaching a diverse group of students (Varelas & Pappas, 2006, p. 214). In this type of read-aloud, students are restricted from engaging spontaneously with the text, having to wait until after the teacher has finished the entire text or until the teacher has given permission to the child to speak (Copenhaver, 2001). This restriction of student talking can lead some students to misbehave, doing whatever it takes to gain the attention they desire (Copenhaver, 2001). Instead of engaging students with the reading process, IRE limits students to gaining content knowledge of the text itself, without the expanded understanding of strategies and deep thinking. Further, this restricted interaction style INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 6 isolates students from diverse backgrounds, including those from minority cultures, races, and low socioeconomic backgrounds, especially in urban schools, from engaging in and feeling comfortable with conversing (Varelas & Pappas, 2006). What separates interactive read-alouds from IRE, or teacher’s monologue, is the melding of content and strategy knowledge within an engaging and authentic environment (Barrentine, 1996). Students are free to express both aesthetic and efferent responses to the text, as they arise, which supports the diverse needs and experiences of all learners (Varelas & Pappas, 2006; Barrentine, 1996). This continuous, push-and-pull interaction with text builds metacognitive awareness and processing ability that goes beyond any one reading of a text (Barrentine, 1996). Despite their expansive reach in positively impacting students of all backgrounds, in a constructivist, student-centered approach most suitable for today’s varied classrooms, interactive read-alouds are being compromised. Given this understanding of interactive and teachers’ monologue read-alouds, the current state of education and the role of read-alouds within it will now be described to make evident the disconnect between research and current practice. Current State of Interactive Read-Alouds: Learning Context The tight hold over teacher’s classroom time has led to rushed, inauthentic read-alouds in which students’ voices and thoughts are not heard. The administration in many schools, because of the pressure to produce data and progress in such short amounts of time, is unsupportive of interactive read-alouds (Fox, 2013; Copenhaver, 2001). Time, rather than student conversations and learning of vocabulary and strategies, is dictating the progression of interactive read-alouds (Kindle, 2009). The lack of time teachers have in the classroom for interactive read-alouds is due to mandated reading programs which segment teachers’ time into small, skill-based sections of INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 7 instruction (Fox, 2013; Copenhaver, 2001). This skill-centered focus is especially prevalent in the younger grades when students are beginning to learn to read (Copenhaver, 2001). However, students in the primary grades need more access to authentic literature to develop a love of and interest in reading, both cultivated through interactive read-alouds (Kindle, 2009; Lane & Wright, 2007). Teacher Compromise To account for these restrictions on time and instruction, teachers are implementing far from best practices for classroom read-alouds; the discussion and engagement inherent in interactive read-alouds is lost. This severely compromised read-aloud instruction was captured in Copenhaver’s study of an experienced elementary teacher of diverse students, Ms. Kathy, across 44 classroom read-alouds (2001). Students’ affective responses to the text, including connections, wonderings, and interactions with classmates, were cut short (Copenhaver, 2001). To keep within the limited time frame, Ms. Kathy refrained from asking open-ended questions, reverting to literal comprehension questions asked primarily after the reading (Copenhaver, 2001). Students’ initiation of questions or comments during the reading were ignored or asked to be kept until after Ms. Kathy was finished reading (Copenhaver, 2001). Only those students who raised their hands were acknowledged and even these students’ comments were limited to being brief and on topic (Copenhaver, 2001). Not only are teachers forced to limit the engagement and authentic talk associated with interactive read-alouds, but they are reducing the amount and quality of teaching when implementing read-alouds (Copenhaver, 2001). Because of the strict time allotments, teachers are less likely to “pursue the teachable moment, the wondering moment, the reflective moment” (Copenhaver, 2001, p. 156). Teachers are skimming the surface of content and strategy INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 8 instruction, choosing books that are easier and more predictable, rather than thought-provoking, rich texts best suited for interactive read-alouds (McGee & Schickedanz, 2007; Copenhaver, 2001). This trend is even more widespread with students who are identified as at risk (McGee & Schickedanz, 2007). Teacher’s current tendencies to favor hasty read-alouds have a trickle down effect on their students. Effects on Students The limited engagement in this classroom context hinders students’ learning and willingness to question and engage in deep thinking (Copenhaver, 2001). Students get a misguided sense of what a read-aloud is, believing that it means to be quiet and only speak when spoken to by the teacher (Fox, 2013; Copenhaver, 2001). Therefore, these experiences are building negative attitudes about reading, further restricting students’ interest in participating (Copenhaver, 2001). While all students are affected by the lack of engagement of these limited, IRE readalouds, students considered marginalized by Copenhaver, specifically those of minority and low socioeconomic background, suffer the most (2001). These students’ behaviors and responses do not fit the narrow expectations of IRE read-alouds, quietly listening and only responding when called on at the end of the story (Copenhaver, 2001). Because these students’ behaviors do not fit the expected practices, they become further isolated from their class, identified as troublemakers (Copenhaver, 2001). Overall, teachers are limiting or watering down their use of interactive read-alouds to compensate for the current expectations in schools (Fox, 2013; Copenhaver, 2001). The current context of read-aloud learning does not take into consideration the many benefits of the interactive strategy. These benefits are described to engrain the necessity of interactive read-alouds in today’s classrooms, in spite of time and testing pressures. INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 9 Benefits of Interactive Read-Alouds Interactive read-alouds are beneficial in primary classrooms because they build students’ motivation for reading, understanding of literary elements, multiple literacy skills, and a sense of cooperation and community (Lane & Wright, 2007; Copenhaver, 2001). Motivation Based on my compilation of research, students’ participation in interactive read-alouds can have a great impact on their attitudes towards reading and the types of books they are motivated to read independently (Kindle, 2009; Morrison & Wlodarczyk, 2009; Lane & Wright, 2007; Fisher et al., 2004). The books teachers choose for read-alouds impact the book choices students make for independent reading (Fisher et al., 2004). In addition to the books chosen for interactive read-alouds, the relationships and communications built throughout the read-aloud process are satisfying for students, boosting their attitude towards reading and sparking their interest in other literacy activities (Fox, 2013; Lane & Wright, 2007). These positive attitudes towards read-alouds go so far as to motivate students to read more in general (Fisher et al., 2004). Vocabulary and Language Beyond the important motivation factor, interactive read-alouds have a measurable impact on students’ vocabulary (Baker et al., 2013; Fox, 2013; Kindle, 2009; Lane & Wright, 2007; Fisher et al., 2004). Because of the direct teaching and dialogue inherent in interactive read-alouds, students are exposed to new words, explicitly and incidentally, especially academic vocabulary, that positively affect students’ reading, writing, and vocabulary knowledge (Kindle, 2009). This exposure to new vocabulary further improves students’ oral language ability, including that of English Language Learners (Fisher et al., 2004). INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 10 A study conducted by Baker and colleagues deepens the evidence for interactive readalouds’ benefits on vocabulary growth (2013). In this comprehensive study of interactive readalouds in 12 first grade classrooms, students who received the interactive read-aloud intervention, in which prescribed lessons included explicit vocabulary and strategy instruction and encouraged student interaction throughout the read-aloud, had significantly improved vocabulary compared to students in the comparison group (Baker et al., 2013). To measure the intervention’s success in improving vocabulary knowledge, students were assessed based on their understanding of 16 vocabulary words - three academic vocabulary words and 13 words from the read-aloud text (Baker et al., 2013). Students in the intervention group, including those students identified as language and literacy at risk, scored an average of 9.35 points higher than students in the comparison group, equivalent to a 35-percentage point variance (Baker et al., 2013). With explicit vocabulary instruction within an interactive read-aloud, students of all ability levels can improve their vocabulary (Baker et al., 2013; Kindle, 2009). In addition to impacting students’ knowledge of vocabulary, interactive read-alouds also improve students’ awareness of text language and structure (Fox, 2013; Kindle, 2009; Morrison & Wlodarczyk, 2009; Fisher et al., 2004). Interactively reading aloud a variety of texts exposes students to the syntactic structure of different genres, thus helping to “promote their syntactic development” (Lane & Wright, 2007, p. 668). Students begin to recognize patterns, making comparisons and insights about different text genres and learning about their differing elements and purposes (Fox, 2013; Fisher et al., 2004). The language of books chosen for interactive read-alouds is rich with detailed descriptions and playful word use that students have not yet been exposed to in their independent reading (Kindle, 2009). Teachers’ expressive reading of these texts, by varying tone, including gestures, and using precise pronunciation of words, helps INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 11 all students better grasp the content of the text and the enjoyment of reading (McCormick & McTigue, 2011; Morrison & Wlodarczyk, 2009). These presentation elements have particular benefits for English Language Learners (McCormick & McTigue, 2011). Interactive readalouds, with their scaffolded teacher support, expose all learners to a variety of language and vocabulary that is then translated to their own reading, writing, and oral language experiences (Lane & Wright, 2007; Fisher et al., 2004). Comprehension Interactive read-alouds also improve students’ comprehension of texts (Baker et al., 2013; Lane & Wright, 2007; Barrentine, 1996). The Baker study, described above, also explored interactive read-alouds’ effects on comprehension through narrative and information retell assessments, finding significant, positive impacts for narrative comprehension (2013). Students who engaged in interactive read-alouds performed around 16 percentile points higher than students in the comparison groups, with those students identified as language and literacy at risk showing the most significant gains (Baker et al., 2013). Through the dialogue of an interactive read-aloud, students are engaging in higher order thinking, which translates to their ability to better comprehend texts (Baker et al., 2013; McGee & Schickedanz, 2007). Connections and Shared Understanding Interactive read-alouds have broader implications for students’ abilities to make connections and create shared learning experiences with peers. A study focusing on interactive read-alouds’ effects on students’ intertextuality was conducted with a class of urban, minority first graders, many of whose primary language was Spanish (Oyler & Barry, 1996). Over the course of 14 interactive read-aloud sessions with information texts, researchers made ethnographic observations focusing on students’ abilities to initiate conversations and make INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 12 connections (Oyler & Barry, 1996). When engaged in an interactive read-aloud, and thus allowed to make connections during the reading, students are more likely to notice details and specific aspects of the text than if they were only engaging at the end of the reading (Barrentine, 1996; Oyler & Barry, 1996). Consistent with Rosenblatt’s transactional theory, the environment created through interactive read-alouds gives all students, including minority students or those often described as being “‘deprived’ of lifeworld experiences,” the ability to make personal and generalized connections to and interpretations of the text (Varelas & Pappas, 2006, p. 251; Mills et al., 2004; Oyler & Barry, 1996). As students work together to make sense of a text in an interactive readaloud (Mills, et al., 2004), they learn to work cooperatively, respect each other’s opinions, and share ownership and control (Varelas & Pappas, 2006). This shared sense of power builds a community of learners, where all students are capable of contributing to the group’s deepened understanding (Fox, 2013; Varelas & Pappas, 2006; Barrentine, 1996; Oyler & Barry, 1996). Constraints of Interactive Read-Alouds Despite these numerous benefits of interactive read-alouds, there are constraints to this method including variance in teacher implementation, narrow student connections and possible distractions, literacy effects, and the need for further research. These limitations point to the necessity of proper implementation in order to draw the most success from this viable means of learning in an elementary classroom. Teacher Variance in Implementation One of the major concerns of interactive read-alouds is the inconsistency in how teachers are structuring and implementing them in their classrooms and how this affects students’ learning (Baker et al., 2013; Kindle, 2009). One study discovered this when researching the best INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 13 practices of interactive read-alouds (Fisher et al., 2004). Twenty-five expert teachers, identified by their principals as conducting successful read-alouds and whose students performed consistently well on reading achievement assessments, from 25 schools were observed by two researchers (Fisher et al., 2004). The practices of these teachers were compared with 120 additional teachers, not identified as experts (Fisher et al., 2004). Non-expert teachers failed to include the following vital aspects of an interactive readaloud: previewing and practicing reading the text prior to instruction, modeling what fluent readers do, and connecting the interactive read-aloud to other literacy or classroom activities (Fisher et al., 2004). These errors in implementation can be synthesized into a lack of planning (Baker et al., 2013; Fisher et al., 2004). Teachers must be intentional in preparing an interactive read-aloud, not viewing it as “an optional activity or a break from the routine of the classroom” for it to be a valuable means of literacy learning (Fisher et al., 2004). Many of these variations in implementation are due to a gap in the amount of research dedicated exclusively to instructional methods for interactive read-alouds (Lane & Wright, 2007; Fisher et al., 2004). There is a great deal of research focused on interactive read-alouds’ positive effects, but less on how to clearly go about using them in the classroom (Lane & Wright, 2007). For example, it was found, as described in the sections above, that discussions throughout the read-aloud are more effective than just after reading, but the particular aspects of this discussion, such as teacher mediation, deemed most beneficial are not as well established (Kindle, 2009). Student Tangents Another concern of interactive read-alouds is the time dedicated to student discussion or the potential for tangents that may take away from the text itself (Kindle, 2009; Barrentine, 1996). Teachers must be cognizant of how much time is spent with students making INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 14 connections, asking questions, or clarifying understandings throughout the read-aloud (Kindle, 2009; Barrentine, 1996). Sometimes, this extended talk can interrupt the flow of the reading and the overall positive experience of the read-aloud (Kindle, 2009; Barrentine, 1996). These tangents, when they stray too far from the story content, can even lower students’ comprehension (Barrentine, 1996). Interactive Read-Aloud Best Practices While additional study is always necessary to continue to improve educational practice, there are notable commonalities across the research on how to best implement interactive readalouds in a way that is meaningful and beneficial for all learners. In order to be successful and further students’ understanding of content knowledge and their reading and processing strategies, teachers must act as knowledgeable and prepared facilitators, imparting good judgment and time management (McGee & Schickedanz, 2007; Fisher et al., 2004; Barrentine, 1996). This facilitation of purposeful learning, with active participation from all students, should occur before, during, and after the reading of a text, with multiple texts on a particular topic of interest read repeatedly (Baker et al., 2013; Kindle, 2009; McGee & Schickedanz, 2007; Fisher et al., 2004). Above all, interactive read-alouds should engage students in deep, connective thinking while staying committed to fostering a love of reading in all students (Lane & Wright, 2007). Teacher’s Role The role of the teacher in an interactive read-aloud is to guide students’ thinking and connection making by building bridges between what students already know and what they can learn (Oyler & Barry, 1996). Throughout an interactive read-aloud, the teacher is pushing further thought by asking questions, prompting conversations, and providing meaningful points of instruction (Kindle, 2009). The teacher has the power to validate students by acknowledging INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 15 their contributions and situating them within a meaningful context for the rest of the class (Copenhaver, 2001; Oyler & Barry, 1996). Thoughtful facilitation is the key to a successful interactive read-aloud (Kindle, 2009). According to the literature, teachers must prepare systematic and detailed interactive read-aloud lessons in order for students to gain from the experience, as meaningful think-alouds about a text take practice (Baker et al., 2013; Fisher et al., 2004; Barrentine, 1996). Practicing reading the text aloud allows teachers to become more fluent, adding necessary expression and intonation, and to prepare meaningful stopping points for discussion and instruction (Fisher et al., 2004). The nature of interactive read-alouds, in which authentic and spontaneous interactions occur, does not mitigate the need for thoughtful preparation (Baker et al., 2013). By organizing points of interest and planning ahead, teachers can anticipate students’ questions and responses to allow for more meaningful and focused dialogue throughout the reading (Baker et al., 2013; McGee & Schickedanz, 2007; Barrentine, 1996). Implementation When implementing an interactive read-aloud, expert teachers, such as those studied by Fisher, read with expression and animation, varying their voice’s volume and tone to fit the text and, therefore, creating students who love listening to texts (2004). Including hand gestures, movement, and props are additional ways to make a read-aloud engaging and to enhance students’ comprehension (Lane & Wright, 2007; Fisher et al., 2004). Reading with animation shows students how spoken language and book language is different and how the way one reads impacts the audience’s retrieval of information (Fisher et al., 2004). Beyond reading with animation, teachers must be mindful of how they engage students with the texts. Successfully implementing an interactive read-aloud can include print referencing INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 16 and dialogic reading, which simultaneously engage students in learning about and from texts and in enjoying text (Lane & Wright, 2007). Print referencing calls students’ attention to specific aspects of a text, such as its structure or function, through cues while reading, like tracking print (Lane & Wright, 2007). By print referencing, students gain an understanding of words and the alphabet, and a metalinguistic awareness of texts (Lane & Wright, 2007). Dialogic reading encourages active engagement and learning through specific question prompts that challenge students’ understanding and through feedback that encourages more sophisticated language and discussion (Lane & Wright, 2007). These methods are most effective when they are incorporated after short amounts of text have been read, rather than at the end of a whole text, so more thoughtful and focused discussion, questioning, and clarifying can take place (Heisey & Kucan, 2010). The cornerstone of interactive read-alouds is the rich and authentic conversation between students and the teacher that take place before, during, and after a reading of a text. As students continue to talk about a text, they gain a more sophisticated understanding, validating the use of spontaneous discussion while reading (Copenhaver, 2001). Interruptions are common and acceptable as students are actively constructing their knowledge, leading to a more meaningful reading experience (Lane & Wright, 2007; Oyler & Barry, 1996). Students’ connections all demonstrate their attempts to better make sense of the text and create, what Rosenblatt deems, their poem (Mills et al., 2004). Teachers should provide feedback to students’ ongoing sense-making, implementing responsive teaching by acknowledging students’ contributions and extending their thinking through further questioning and prompts for peer discussion (Baker et al., 2013; Barrentine, 1996). Paying special interest to students’ comments and questions allows teachers to “use them INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 17 as windows for peering into their [students’] thinking,” thus, a valuable means of informal assessment (Barrentine, 1996, p. 42). The teacher’s facilitation of these spontaneous discussions ensures that there are fewer misconceptions or confusions than when discussion takes place only after reading (Baker et al., 2013; Lane & Wright, 2007). This consistent involvement ensures that students are taking an active role in their learning and understanding. Recommendations: Interactive Read-Alouds for Cross-Curricular Integration Based on the above research and synthesis indicating the strengths and implementation of interactive read-alouds and the reality teachers are facing in today’s classrooms, in which time and deep learning are limited, I recommend using interactive read-alouds as a medium for crosscurricular learning. The startling contrast between what interactive read-alouds should be and how they actually are being implemented in schools today is too great to not take action. Teachers “have an ethical and professional obligation to speak out [as]...the costs of not fighting to slow down, read, and really talk are simply too high” (Copenhaver, 2001, p. 157). Crosscurricular read-alouds are a way to provide students with the additional content they need, such as the diminishing subject of science in primary classrooms, in a context that is authentic, engaging, and interactive for all students (Barber et al., 2006; Doiron, 1994). This integration ensures that interactive read-alouds are being implemented according to best practices, while accounting for the need to use instructional time efficiently and wisely (Lane & Wright, 2007). Interactive read-alouds as a means for cross-curricular integration, particularly of science whose information is presented as nonfiction, allows for multiple skills and topics to be taught concurrently, thus saving instructional time (Lane & Wright, 2007). With the Common Core State Standards’ heavy emphasis on students of all ages reading more nonfiction texts, this strategy becomes even more relevant. By incorporating factual information in the form of INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 18 literature into our interactive read-alouds, students will learn to value and enjoy nonfiction, subject-specific information (McCormick & McTigue, 2011; Doiron, 1994). To support my research-based recommendations, I will next present the benefits of cross-curricular read-alouds, both broadly and explicitly related to science instruction. I will then provide suggestions for implementing these integrated read-alouds in the current classroom. Benefits of Cross-Curricular Integration As the content of informational texts can be harder to grasp, interactive read-alouds provide a desirable medium to engage students in this rigorous content (Heisey & Kucan, 2010). Interactive read-alouds of informational texts tap into students’ natural curiosity about the world and present this factual information in a way that excites and peaks their interest (Doiron, 1994). Teacher facilitation of interactive read-alouds of informational texts provides students the support they need while encouraging active discussion of neglected informational subjects (Baker et al., 2013). The context of an interactive read-aloud provides the bridge to incorporating more informational texts into students’, especially primary students’, instruction and independent reading interests (Baker et al., 2013; Heisey & Kucan, 2010; Doiron, 1994). By incorporating subject-specific information with the strategies and skills of literacy through an interactive read-aloud, students benefit in a number of ways. Interactive read-alouds allow for more cohesion across the curriculum, thus students’ language across all subject areas improves (Fisher et al., 2004). Students’ comfort level with reading and comprehending informational texts is enhanced due to the focused instruction and increased exposure (Doiron, 1994). And, as with all interactive read-alouds, students’ ability to problem-solve and think critically is heightened (Varelas & Pappas, 2006; Doiron, 1994). INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 19 Benefits of Science Interactive Read-Alouds Science, one of the most neglected subjects in primary school, can be taught successfully through interactive read-alouds (Barber et al., 2006). Integrating science with literacy has multiple benefits over teaching literacy and science in isolation, thus saving time and using instructional opportunities wisely. Students in 2nd and 3rd grades, over 8 weeks and 62 classrooms, participated in a study to measure the impact of combined science and literacy approaches, through interactive read-alouds, as opposed to science-only or literacy-only comparison approaches, on science content knowledge (Barber et al., 2006). Students who were involved in interactive read-alouds of science texts, with discussions occurring before, during, and after reading, had increased literacy skills and understanding of science concepts when compared to peers involved in the science-only or literacy-only activities (Heisey & Kucan, 2010; Barber et al., 2006). When time is so limited in today’s classrooms, interactive readalouds of science texts should be utilized, as they are effective in improving students’ science content knowledge and literacy processes (Barber et al., 2006; Varelas & Pappas, 2006) Science interactive read-alouds expose young learners to complex scientific concepts and vocabulary that they wouldn’t access if just reading independently (Heisey & Kucan, 2010; Barber et al., 2006). The nature of an interactive read-aloud is conducive to the type of exploration and inquiry that is promoted by science education standards (Varelas & Pappas, 2006). As students wonder throughout a reading, they are able to co-construct scientific knowledge with their peers and teacher, learning important scientific discourses (Varelas & Pappas, 2006). Teachers’ readings expose students to authentic thinking about science, modeling scientific questioning, observation, and explanations (McCormick & McTigue, 2011; Varelas & Pappas, 2006). Students can merge their own hands-on science experiences with the content of INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 20 the read-aloud to further develop their understanding (Varelas & Pappas, 2006). The interactive read-aloud portion of the learning makes the science content concrete and accessible for students (McCormick & McTigue, 2011). Students learn the particular structures and vocabulary specific to scientific writing and are able to explore these qualities through authentic text discussions (Varelas & Pappas, 2006). Implementation of Science Interactive Read-Alouds To implement an effective, science interactive read-aloud, teachers must choose books that bring science concepts to life through an engaging voice, as opposed to dryly presenting scientific information from textbooks (McCormick & McTigue, 2011). The barometer for a quality science trade book for an interactive read-aloud is “how well the author transforms the abstract science topics into a meaningful, attention-grabbing, and digestible form for the novice (and possibly reluctant) scientist to absorb” (McCormick & McTigue, 2011, p. 46). These science trade books, “not only inform but also challenge, motivate, and stimulate the reader to read more about a subject” (Doiron, 1994, p. 620). Books of this sort can be found on the National Science Teachers Association yearly list of chosen quality science trade books (McCormick & McTigue, 2011). Implementing an interactive read-aloud of a science text requires the same features as implementing an interactive read-aloud of any other text. Teachers must prepare ahead of the reading, set and share a purpose for reading, read expressively, and engage students in continuous, authentic discussion throughout a reading, acknowledging students’ contributions and encouraging critical thinking (McCormick & McTigue, 2011; Varelas & Pappas, 2006). Particular nuances of reading a science text include the types of questions asked and the great importance of engaging students during reading (Heisey & Kucan, 2010). In addition to INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 21 questions focused on the content and themes of the text, asking students to make connections between the focus text and other texts and experiences is particularly valuable (Heisey & Kucan, 2010). When students are asked to make connections across science texts teachers are building “students’ developing representation of scientists at work by prompting them to explicitly compare, contrast, and connect information” (Heisey & Kucan, 2010, p. 669). This questioning and further engagement should occur during a reading, evidenced by Heisey & Kucan’s study of two 1st/2nd grade classrooms of diverse students (2010). One class discussed the science text after-reading and the other during-reading. The during-reading group, based on a pre- and post-test questioning assessment, displayed a more comprehensive understanding of the science concepts, providing more textual evidence to support their claims, and thus, a deeper understanding than the after-reading group (Heisey & Kucan, 2010). Because the students in the during-reading group were given more prompts and opportunities to express their wonderings and connections, they developed a greater understanding of the science texts and their underlying concepts (Heisey & Kucan, 2010). This cross-curricular integration of science and literacy in interactive read-alouds illustrates the benefits of implementing this multifaceted strategy in today’s classroom. Conclusion With their widespread ability to reach learners of all backgrounds in an engaging, motivating, and instructionally beneficial way, interactive read-alouds should have a distinct place in today’s elementary classrooms. But, their implications for practice in today’s pressureridden classrooms require teachers to be more strategic and cognizant of interactive read-alouds’ implementation. With the current restrictions of time sensitive schedules and prescribed programs weighing heavily on teachers, adjustments need to be made to meaningfully INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 22 incorporate this aspect of a reading program. Cross-curricular interactive read-alouds allow for efficient and beneficial use of classroom time, while preserving best practices and providing students with necessary scaffolding of content knowledge and literary strategy use. Despite this feasible route, I question whether the research on this solution will be enough to overcome teachers’ daily conflicts. Will teachers be able to look beyond interactive read-alouds’ limitation of time consumption and focus instead on the greater picture of student success in literacy and science, therefore overcoming contextual pressures? Or will teachers resort to the easier, though insufficient IRE read-alouds or no read-alouds at all, leaving students without needed opportunities for analytic thinking and development of science content knowledge? This conflicted context implies that teachers must be dedicated problem-solvers, working past their structural limitations to provide the best means of instruction for all their students. Through interactive read-alouds, students are able to push their thinking, engage in active discussions, and develop an authentic relationship with reading. Extending interactive readalouds to science texts only furthers students’ ability to problem-solve and make sense of abstract content. By utilizing interactive read-alouds, teachers are putting students first, developing them into the type of deep thinking, collaborative individuals necessary to be successful in today’s complex world. I hope further research will be done to explore additional cross-curricular strategies that will help develop students’ literacy and subject-specific knowledge in an efficient and engaging context. Given teachers’ limited time, integrative teaching methods need to be researched so students are provided with rich content and a more realistic view of learning. Building from the successes of interactive read-alouds of science texts, I believe more seamless cross-curricular learning will allow for more effective use of class time and make learning increasingly authentic and meaningful for all students. INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 23 References Baker, S. K., Santoro, L. E., Chard, D. J., Fien, H., Park, Y., & Otterstedt, J. (2013). An evaluation of an explicit read aloud intervention taught in whole-classroom formats in first grade. The Elementary School Journal, 113(3), 331-358. doi: 10.1086/668503. Barber, J., Nagy-Catz, K., & Arya, D. (2006, April). Improving science content acquisition through a combined science/literacy approach: A quasi-experimental study. Paper presented at the annual conference of the American Educational Research Association, Berkeley, CA. Barrentine, S. (1996). Engaging with reading through interactive read-alouds. The Reading Teacher, 50(1), 36-43. Copenhaver, J. F. (2001). Running out of time: Rushed read-alouds in a primary classroom. Language Arts, 79(2), doi: 10.2307/41483218. Doiron, R. (1994). Using nonfiction in a read-aloud program: Letting the facts speak for themselves. The Reading Teacher, 47(8), 616-624. Fisher, D., Flood, J., Lapp, D., & Frey, N. (2004). Interactive read-alouds: Is there a common set of implementation practices?. The Reading Teacher, 58(1), 8-17. doi: 10.1598/RT.1.1. Fox, M. (2013). What next in the read-aloud battle?. The Reading Teacher, 67(1), 4-8. Heisey, N., & Kucan, L. (2010). Introducing science concepts to primary students through readalouds: Interactions and multiple texts make the difference. The Reading Teacher, 63(8), 666-676. doi: 10.1598/RT.63.8.5. Kindle, K. (2009). Vocabulary development during read-alouds: Primary practices. The Reading Teacher, 63(3), 202-211. doi: 10.1598/RT.63.3.3. INTERACTIVE READ-ALOUDS 24 Lane, H. B., & Wright, T. L. (2007). Maximizing the effectiveness of reading aloud. The Reading Teacher, 60(7), 668-675. doi: 10.1598/RT.60.7.7. McCormick, M. K., & McTigue, E. M. (2011). Teacher read-alouds make science come alive. Science Scope, 34(5), 45-49. McGee, L. M., & Schickedanz, J. A. (2007). Repeated interactive read-alouds in preschool and kindergarten: the repeated interactive read-aloud technique is a research-based approach to comprehension and vocabulary development in preschool and kindergarten. The Reading Teacher, 60(8), 742-751. Mills, H., Stephens, D., O'Keefe, T., & Waugh, J. R. (2004). Theory in practice: The legacy of Louise Rosenblatt. Language Arts, 82(1), 47-55. Morrison, V., & Wlodarczyk, L. (2009). Revisiting read-aloud: Instructional strategies that encourage students' engagement with texts. The Reading Teacher, 63(2), 110-118. Oyler, C., & Barry, A. (1996). Intertextual connections in read-alouds of information books. Language Arts, 73(5). Varelas, M., & Pappas, C. C. (2006). Intertextuality in read-alouds of integrated science-literacy units in urban primary classrooms: Opportunities for the development of thought and language. Cognition and Instruction, 24(2), 211-259.