Rose-Honors Thesis

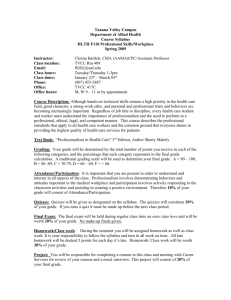

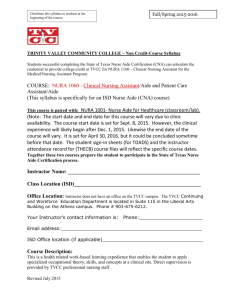

advertisement