Class Lecture Notes 4.doc

advertisement

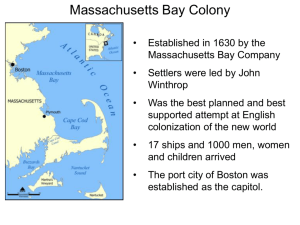

The American Promise – Lecture Notes Chapter 4 - The Northern Colonies in the Seventeenth Century, 1601-1700 Puritans and the Settlement of New England (Slide 2) Page 83 A. Puritan Origins: The English Reformation 1. Henry VIII and the English Reformation—Henry VIII recognized that the Protestant Reformation offered him an opportunity to break with Rome and take control of the church in England; he initiated the English Reformation in 1534; at his insistence, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy, which outlawed the Catholic Church and proclaimed the king the head of the Church of England; still, he sought no more than a halfway Reformation and remained an orthodox Catholic in his beliefs. 2. Puritans—Puritans were Protestants who called for a genuine, thoroughgoing Reformation; Puritanism was less an organized movement than a set of ideals and religious principles that appealed to dissenting members of the Church of England; they sought to eliminate what they saw as the offensive features of Catholicism that remained in the Church of England, such as hierarchy and rituals. 3. Waxing and Waning of Protestantism in England—Fate of Protestantism waxed and waned after Henry died in 1547; James I and Charles I were especially unreceptive to Puritan ideas; in 1629 Charles I dissolved Parliament, where Puritans were well represented, and initiated aggressive anti-Puritan policies; many Puritans chose to emigrate, with the largest number going to America. B. The Pilgrims and Plymouth Colony 1. Pilgrims—Pilgrims endorsed separatism; they wanted to withdraw from the Church of England, which they considered hopelessly corrupt; they first moved to Holland in 1608. 2. William Bradford—Bradford was a leader of the Pilgrims, and he believed that America promised to better protect their children’s piety and preserve their community; separatists obtained permission to settle in the territory granted to 1 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes the Virginia Company; 102 immigrants boarded the Mayflower in August 1620, and after eleven weeks at sea, they arrived in present-day Massachusetts. 3. Mayflower Compact—The Pilgrims realized immediately that they were north of Virginia and had no legal authority to settle the land; nevertheless, they drew up the Mayflower Compact to provide order and security as well as a claim to legitimacy. 4. Plymouth Settlement—Pilgrims settled at Plymouth and elected Bradford their governor; the first winter was devastating, and half of the settlers died; Wampanoag Indians rescued the settlement that spring; Squanto taught the settlers to grow corn and told them how to get fish; celebrated in the fall of 1621 with a feast of Thanksgiving attended by Chief Massasoit and other Wampanoags; the settlement remained precarious and failed to attract many other English Puritans. C. The Founding of Massachusetts Bay Colony (Slide 3) Page 86 1. Massachusetts Bay Company—In 1629, a group of Puritan merchants and country gentlemen obtained a royal charter for the Massachusetts Bay Company; granted land for colonization in present-day Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, Maine, and upstate New York; a unique provision permitted the government of Massachusetts to be located in the colony rather than in England; Puritans went from oppressed minority to self-government. 2. John Winthrop—Stockholders of the company elected prosperous lawyer John Winthrop as governor; while on board the ship the Arabella, Winthrop delivered his famous “city on a hill” sermon that proclaimed the Puritans’ colony would set a religious example for the rest of the world. 3. Early New England—Religious fervor and the desire to create a city on a hill shaped early New England as profoundly as tobacco shaped the Chesapeake; strengthened colonists’ desire to obey God’s laws; more than 20,000 Puritans came to Massachusetts; by 1640, New England had one of the highest ratios of preachers to population in all of Christendom; on the whole, immigrants came from the middle ranks of English society; most were farmers or tradesmen; only one-fifth came as indentured servants; also unlike the Chesapeake, most immigrants arrived as families; Puritans considered each family a “little commonwealth” that mirrored the hierarchy among all God’s creatures; young people were subordinate to their elders, children to their parents, and wives to their husbands; New England’s social order was defined by the interlocking institutions of family, church, and community. 2 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes The Evolution of New England Society (Slide 8) Page 89 A. Church, Covenant, and Conformity 1. Puritan Protestantism—Puritans believed that the church consisted of men and women who had entered into a solemn covenant with one another and with God; Puritans embraced a version of Protestantism derived from Calvinism; Puritans believed in predestination, that God had decided before the creation of the world which humans would receive eternal life; only God knew the identity of these fortunate individuals, known as the “elect” or “saints”; nothing a person did could alter his or her fate, but Puritans believed if a person lived a godly life that his or her behavior would reflect his or her status as one of God’s chosen few; Puritans thought that visible saints—people who passed tests of conversion and church membership—probably, but not certainly, were among God’s elect. 2. Church—Church members kept an eye on the behavior of everyone in town and thus enforced a remarkable degree of religious conformity; total conformity was never achieved; despite the central importance of churches, they played no role in civil government; the Puritans did not want to mimic what they viewed as the corrupt practices of the Church of England. 3. Strict Moral Laws—Religious beliefs still influenced governments; fines were issued for Sabbath-breaking activities such as working, traveling, or playing a flute; religious wedding ceremonies were outlawed; elaborate clothing and finery were prohibited. B. Government by Puritans for Puritanism 1. General Court—Company stockholders, known as freemen, met as a body known as the General Court and made the laws needed to govern the company’s affairs. 2. Freemen and “Inhabitants”—In 1631, all male church members were deemed freemen; only freemen could vote for governor, deputy governor, and colonial officials; all other men were classified as “inhabitants”; they could vote, hold office, and participate fully in town government. 3 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 3. “Town meeting”—A town meeting, composed of inhabitants and freemen, chose the selectmen and other officials who administered local affairs; routinely practiced a level of popular participation in politics unprecedented anywhere else in the world; almost every adult man could speak out and vote, but all women were prohibited from voting. 4. Land Distribution—Land distribution was one of the most important functions of New England town governments; unlike in the Chesapeake, land was more or less equally distributed; town founders apportioned land among themselves and any newcomers they permitted to join them; the physical layout of towns encouraged settlers to look inward toward their neighbors. C. The Splintering of Puritanism (Slide 11) Page 92 1. Different Visions of Godliness—Individual Bible study and the promise of a godly society led New Englanders toward different visions of godliness; Puritan leaders interpreted dissent as an error caused either by a misguided believer or by the malevolent power of Satan; dissenters could not be tolerated. 2. Roger Williams—Williams argued that forcing non-Christians to attend church constituted “false worshipping” and “spiritual rape”; he argued that since only God knew the truth, New England should practice religious toleration; Winthrop banished him from the colony; he escaped deportation back to England and settled Rhode Island. 3. Anne Hutchinson—Hutchinson gave weekly lectures on recent sermons to crowds of sixty to eighty people; she expounded on the sermons of John Cotton, which stressed the covenant of grace, the idea that individuals could be saved only by God’s grace in choosing them to be in the elect, which contrasted to the covenant of works, the belief that behavior can bring salvation; Cotton’s sermons hinted that many Puritans were guilty of embracing Arminianism, or a belief in the covenant of works; Hutchinson agreed; her lectures alarmed Winthrop, who believed she was subverting social order; Winthrop referred to Hutchinson and her followers as antinomians, or people opposed to God’s law as set forth in the Bible and as interpreted by the colony’s leaders; elders accused her of the heresy of prophesy and excommunicated her in 1638. 4. Thomas Hooker—Hooker clashed with Winthrop over the constitution of the church; he believed that men and women who lived godly lives should be admitted to church membership even if they had not experienced conversion; this 4 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes argument had political ramifications, as only church members could vote; Hooker led an exodus of more than 800 colonists to the Connecticut River Valley; founded Hartford and neighboring towns which, in 1639, adopted the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, a quasi-Constitution. D. Religious Controversies and Economic Changes (Slide 12) Page 94 1. Puritan Revolution Slows Immigration to New England—The Puritan Revolution, led by Oliver Cromwell, ended with the execution of Charles I and the proclamation of England as a Puritan republic; this meant that Puritans in England, not New England, were reforming English society; immigration slowed as a result. 2. New England’s Economy—Fewer boats to New England increased the prices on scarce English goods and cut off customers from colonial products; had to find domestic products; fish became the most important export, and it stimulated colonial shipbuilding. 3. Puritanism Is Challenged—Population continued to grow through natural increase, doubling every twenty years; piety of the founders lessened; population grew faster than church membership; many children of “visible saints” failed to experience conversion and attain full church membership; to solve this problem, in 1662, a synod of Massachusetts ministers established the Halfway Covenant; allowed the unconverted children of visible saints to become “halfway” church members—they could baptize their infants but could not participate in communion or vote. New England still enforced piety, however, as evidenced by the treatment of Quakers with ruthless severity; New England’s limited success in establishing a godly society undermined the appeal of Puritanism; Salem witch trials only increased the gnawing doubt about the strength of Puritan New Englanders’ faith. The Founding of the Middle Colonies (Slide 14) Page 97 A. From New Netherland to New York 1. Dutch East India Company and Henry Hudson—In 1609, the Dutch East India Company sent Hudson to look for a Northwest Passage to Asia; he sailed the Atlantic coast and traveled up the river that now bears his name. 5 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 2. New Netherland—A decade later, the Dutch government granted the West India Company exclusive rights to trade with the Western Hemisphere; company director Peter Minuit purchased Manhattan Island from the Manhate Indians for trade goods worth the equivalent of a dozen beaver pelts; New Amsterdam became the central trading center in New Netherland; New Netherland did not attract many European immigrants; though few in number, New Netherlanders were remarkably diverse in religious beliefs and ethnic origins compared to the English settlers in New England and the Chesapeake; the West India Company created resentment among the colonists by never allowing them to form a representative government; New Netherland became New York when the English demanded New Netherland governor Peter Stuyvesant surrender the area to the British; new proprietor the Duke of York permitted religious toleration not because he believed in liberty of conscience but instead because he recognized the heterogeneity of the colony. B. New Jersey and Pennsylvania 1. Duke of York Subdivides His Grant—The Duke of York subdivided his land grant and gave the portion between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers to two of his friends; the proprietors of this colony, New Jersey, quarreled and called in English Quaker William Penn to arbitrate their dispute. 2. William Penn—Penn settled the dispute and became interested in establishing a genuinely Quaker colony in America; Quakers believed in an open, generous God who made his love equally available to all people; Quaker leaders were ordinary men and women, and women assumed positions of religious leadership; these beliefs and practices continually brought them into conflict with the English government; Penn remained on good terms with Charles II; partly to rid England of the Quakers, in 1681, Charles made Penn the proprietor of a new colony called Pennsylvania. C. Toleration and Diversity in Pennsylvania (Slide 16) Page 100 1. English Quakers Flock to Pennsylvania—Between 1682 and 1685, nearly eight thousand immigrants arrived, most of whom were artisans, farmers, and laborers. 2. Ethnic Diversity—Immigrants came from England, Ireland, and Wales; Quaker missionaries also encouraged immigrants from the European continent, giving Pennsylvania greater ethnic diversity than any other English colony except New York. 6 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 3. Peace with the Indians—Penn was determined to live in peace with the Indians; he dealt with Indians fairly as an expression of his Quaker ideals; he instructed agents to purchase Indian land, respect their claims, and deal with them fairly. 4. Religiously Tolerant—Pennsylvania also tolerated Protestant sects of all kinds as well as Roman Catholicism; voters and officeholders had to be Christians, but the government did not compel settlers to attend church or levy taxes to maintain a state-sponsored church. 5. Evolution of Local Government—Penn used civil government to enforce religious morality; he had extensive powers subject only to review by the king; he stressed that the exact form of government mattered less than the men who served in it. The Colonies and the English Empire (Slide 17) Page 101 A. Royal Regulation of Colonial Trade 1. Navigation Acts—The Navigation Acts of 1650, 1651, 1660, and 1663 set forth two fundamental rules governing colonial trade; first, goods shipped to and from the colonies had to be transported in English ships using primarily English crews; second, certain enumerated products could only be shipped to England or to other English colonies; affected Chesapeake tobacco more than New England and middle colonies’ exports. 2. Colonial Commerce Regulated by Royal Supervision—By the end of the seventeenth century, colonial commerce was defined by regulations that subjected merchants and shippers to royal supervision and gave them access to markets throughout the English empire; colonial goods counted for one-fifth of all English imports, and the colonies absorbed more than one-tenth of English exports. B. King Philip’s War and the Consolidation of Royal Authority Page 103 1. Monarchy Seeks Greater Control over Colonies—The English monarchy took steps to exercise greater control over colonial governments; Charles II took particular interest in harnessing Puritan New England; the opportunity for a royal investigation arose after King Philip’s War. 7 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 2. King Philip’s War—In 1675, warfare between Indians and colonists erupted in the Chesapeake and New England; colonists emerged triumphant from King Philip’s War; the war left New Englanders with an enduring hatred of Indians, a large war debt, and a devastated frontier. 3. Dominion of New England—A royal investigation concluded that the colonists had deviated from English rules; English government decided to govern New England more directly; in 1684, an English court revoked the Massachusetts charter; two years later, royal officials incorporated Massachusetts and the other colonies north of Maryland into the Dominion of New England, governed by Sir Edward Andros. In England in 1688, the Glorious Revolution reasserted Protestant power and emboldened colonial uprisings against royal authority in Massachusetts, New York, and Maryland; in 1689, the rebellious colonists destroyed the Dominion of New England, overthrew Andros, and reestablished the former charter governments in both Massachusetts and New York; rebel governments did not last long, and the crown soon reestablished royal control of the colonies; in 1691, Massachusetts became a royal colony, and landowners, rather than church members, could vote in colony-wide elections. 4. Threats from New France—Colonists still valued English protection from hostile neighbors; they worried that the Catholic colony of New France menaced frontier regions by encouraging Indian raids and by competing for the lucrative fur trade; when the English colonies were distracted by the Glorious Revolution, the French attacked villages in New England and New York in King William’s War; the war ended inconclusively, but it reminded colonists that along with English royal government came a welcome measure of military security. 8 of 8