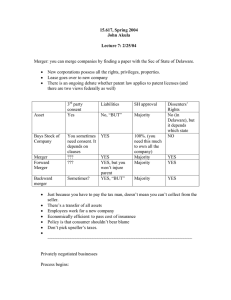

Katz

advertisement