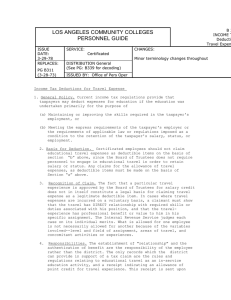

I. Introduction A. The Several Sources of Tax Law:

advertisement