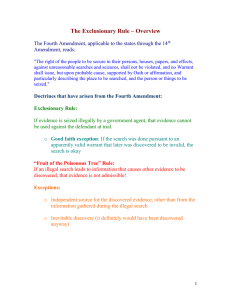

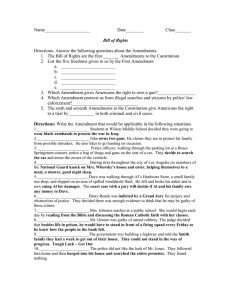

C P Examples and Explanations:

advertisement