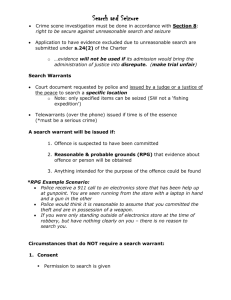

Schaffer Part 1of 2

advertisement