Theory of Business Organization

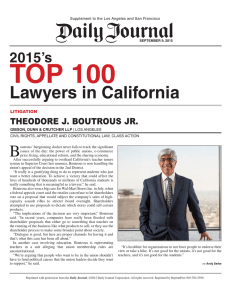

advertisement