12598516_ADF DRUG CONTROL.short.doc (51.5Kb)

advertisement

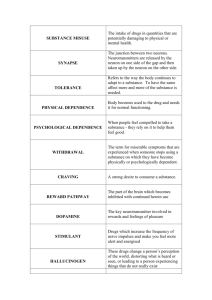

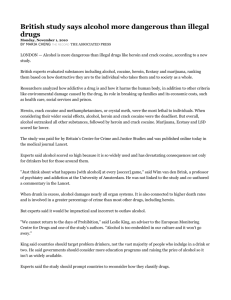

Documents/adf drug.control.short.doc THE DRUG CONTROL PROBLEM Half-hour keynote address to the ADF Winter Symposium, Brisbane, QLD, 4-7 July 2005. Emergence of the Drug Problem The emergence Zealand, of an Australia, identified Britain, and drug problem many other in New western nations, occurred less than 40 years ago. It’s been with us ever since. What I intend to do in this paper is to look at the drug problem in NZ and internationally, and make some general observations about the effectiveness of drug control measures. Drug Use in NZ In NZ, drug use has risen inexorably since first being ID’d in the late 1960s. Here, increasing usage is drug offences reported roughly to the reflected in annual police, which exponentially from: [graph police-reported drug offences] 125 in 1966 1 grew 745 in 1971 9,000 in 1981 20,000 in 1991 27,000 in 1994 (peak) It has now apparently reached saturation point and over the past 10 years has settled at about 24,000 recorded offences p/a. As in most countries, 90% of these reported offences involve cannabis. Control Measures in NZ These meteoric rises notwithstanding, a great deal of energy has been expended, and a wide range of measures has been created, to try to control it. They are too numerous to recite in detail, but the principal steps have involved: * Increasing criminal intelligence networks both nationally and internationally; * Tightening border controls; * Giving police greater search and investigation powers; * Giving suspicious police greater financial powers transactions to and investigate confiscate assets believed have been criminally obtained; 2 * Controlling the supply of precursor substances used in local MFG; * Increasing the maximum penalties available for dealing in illegal drugs. NZ currently spends $224m p/a on preventing/reducing harm caused by tobacco, alcohol, and drug abuse. Of this: $32m (14%) goes on demand reduction. $52m (24%) goes on treatment services. But the bulk: $139m (62%) goes on law enforcement and control. Effectiveness of Drug Control Measures How effective have these drug control measures been? In NZ, there are a few instances of control activity having demonstrably impacted on the availability of illegal drugs. EG. Rigorous police and customs activity was successful in staunching the importation of heroin and marijuana to NZ in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Imported MJ and heroin are still rare in NZ. Large drug busts have certainly also had an impact on the quantities and prices of drugs available on the streets. 3 However, if we look at the problem historically, it is clear that attempts to stop or even significantly reduce the supply of illegal drugs in the long term have failed. The control of imported marijuana and heroin simply resulted in these drugs being replaced by local product: * Imported MJ has been replaced by high-quality homegrown ‘NZ Green’. Today Marijuana is freely available, it is relatively cheap ($200-$400/oz), and 20% of the population aged 15-45 report they have used it in the past year (2002). * Heroin has been replaced by Homebake [ ] and MSTs [ ]. Although imported heroin is seldom seen, opiates are now cheaper and easier to get than ever. A non-habituated user can get off for as little as $15.00. In spite of this, however, NZ doesn’t seem to have a serious opiate abuse problem. This is partly because of the program, which has 3,500 clients, 4 Methadone maintenance but it’s also due to the fact that opiates are not ‘in’ with young people these days. Only 1% 15-45 y/o report past-year usage, and this figure is slightly declining. LSD, another popular drug in former times, is similarly unfashionable, with past-year usage low and dropping from 3.8% to 3.2% since 1998. The drugs that are trendy these days are the so-called ‘party drugs’, or ATS drugs, like Ecstasy and Methamphetamine. Attempts to control the new drugs have been markedly unsuccessful. The Ecstasy trade is accelerating rapidly and the price of ‘E’ is stable at $40-$80.00. 3.4% of 15-45 year-olds report past-year usage - more than double the 1998 figure. Amphetamine is even more popular. Indications are that despite the huge amount of attention being paid to controlling it, amphetamine use is rising. 5% of 15-45 year-olds report past-year usage, which is almost twice the 1998 figure, And supply is such that the price of a gram has fallen from $1,000 to $600-$800 in the last year or so. 5 But Meth’s expensive: $100 a point. Those who can’t afford the expense of Meth are using Ritalin, which is cheap on the streets and readily available from doctors for kids with ADHD. Ritalin scripts rose from 2,900 in 1993 to 72,000 in 2002. A lot of people are shooting up Rit., which has similar properties to Meth. So where drug use patterns have changed, it has been the fashions of youth culture and shifts in user demand, rather than police activity that have had the greatest impact. The International Picture NZ is not unique in its failure to control the illegal drug supply. In the United States, which spends $6.2 billion a year on drug control and currently has 1.3 million drug offenders in prison, the 20-year long ‘war on drugs’ [started by Pres. Reagan in the 1980s] has had little demonstrable effect. The USA has one of the highest youth use prevalence rates in the world. 6 Here, a drop in illegal usage the 1980s was followed by an increase in the 1990s. Between 2001 and 2003, an 11 percent drop in past-month illegal drug use in America was offset by a steep increase in misuse of potentially dangerous prescription narcotics like Vicodin and OxyContin. In Australia there was a documented and significant ‘heroin drought’ between 2000 and early 2002 which was partially caused by a 606kg heroin bust in the summer of 2000 - ie law enforcement. But another factor in the Australian drought was a fall in the poppy harvest in Myanmar, accompanied by growing demand for heroin in China. The limited heroin stock became diverted to satisfy the massive Chinese market. Important, too, is the fact that in Australia, at the same time as heroin became scarce and more expensive, there was a coincidental rise in the availability of methamphetamine from the Golden Triangle area; the same area that the heroin was coming from. This suggests that when heroin grew difficult to procure, importers simply substituted their products. 7 Moreover, at the same time there was a sharp increase in robberies and thefts as rising prices forced heroin users to take desperate measures to support their habits. Another example of this so-called ‘substitution effect’ was in Thailand, where a ‘War on Drugs’ saw the execution of over 2,000 alleged drug dealers in 2003. [The ‘Final Solution’?] Here, a temporary heroin drought resulted in a rise in use of cocaine, amphetamines, solvents and cheap whisky. And as in Australia, there was also a rise in property crime. So apart from resulting in the deaths of 2,000 people, the Thai ‘War on Drugs’ generated other problems. In fact, from an examination of international literature, it’s difficult to find an evidence-based example of a drug control policy that has had a sustained impact anywhere in the Western world. The only countries eradication of that illegal have drugs succeeded are closed in long-term authoritarian nations such as Maoist China and the old Soviet Union, which: * operated behind iron curtains 8 * controlled all aspects of economy and * suppressed human rights. The opening up of both states since the 1980s has resulted in an explosive drug problem. Execution of drug dealers and long mandatory sentences for drug possession have had little effect. Internationally, occasional examples of successful drug control strategies have generally been short-lived. Prevalence control figures measures, tend and to fluctuate are driven independently primarily by of the cyclical nature of youthful drug trends. That is, kids will tend to use whatever drug happens to be fashionable, and the market then responds to the demand. Accordingly, a drop in the prevalence of one type of drug is normally matched by a rise in another. This is simple economics: When supply of a particular drug is short, prices are driven up as dealers struggle to maintain their incomes. Rising costs force addicts into more crime in order to support their habits. Meanwhile recreational drug users, whose choice of drugs is affected by prices, search for new and cheaper drugs. 9 Dealers respond to market forces and supply whatever is in demand. Moreover, there is evidence internationally of a significant research investment in the production of new ‘designer drugs’ that are not yet illegal. These will inevitably fill any gaps that are created by effective law enforcement. It is unlikely that this can be stopped and, given the profits available, it is equally unlikely that it will ever end. Effective Drug Control So where does this leave us in terms of drafting a drug control strategy? The use of recreational drugs precedes the advent of civilisation and has remained ever since. The amount and variety of drug use in the world today is greater than at any other time in world history, and is likely to continue to increase. Evidence shows that successful supply reduction will tend to be short-lived unless effective action can be taken to reduce endemic demand. 2 factors need to be born in mind here: 10 1. Different classes of drug have different properties and different dangers associated with them: * Some are automatically addictive, some aren’t. * Some can be injected, some can’t. * The potential of fatal overdose varies from high in some drugs to zero in others. * Some severely impair driving ability, some don’t. * Some are alcohol), inclined some to have make the people opposite violent (eg effect (eg Ecstasy). * And the potential for damage from long-term usage varies significantly from one drug to the next. So to talk in terms of overall reductions in drug abuse means nothing, unless the types of drugs involved are specified. EG. If marijuana use was halved, and amphetamine use increased by 50%, then I’d call this a negative outcome. Drug control policies need to target the more dangerous drugs, and they need to do so in a way that minimises the chance of a worse drug being substituted. 11 2. The majority of illegal drugs that are available have legitimate medical uses, and are relatively harmless provided they’re used intelligently: That is, if they aren’t used in large doses, or they aren’t used too often. Most illegal drug users are occasional or opportunistic dabblers, and will experience few deleterious effects from their use. In NZ, for example, although an estimated 1 million tabs of ‘E’ are used each year, there have only been 3 deaths from the drug and it has produced very little evidence of medical morbidity or dependency. Methamphetamine is reportedly used year, but only 1/3 by 84,000 people a report using it more than once a month. In 2002, only about 40 people presented in Auckland hospitals [ ] with meth-related conditions, and Amphetamines have been associated with a total of only 5 deaths in total. Alcohol kills 400 p/a and 100 in road crashes. 12 From this it is hard to deduce that Amphetamine use causes serious problems for any but a small proportion of users. It appears that only a minority of users abuse amphetamines to the point where they become psychotic and a danger to others or to themselves. If a drug control policy halves the amount of meth being used, but the policy only affects the casual users without impacting on the habituals, then the danger of the drug remains and the policy can be considered a failure. Conclusion In my submission, those who draft drug control policies need to recognise these factors. History shows that policies aimed at eradication of drugs have never been successful in free democratic societies and as such are probably doomed to failure. Harm reduction is, however, a realistically attainable outcome. If this is to be achieved, the ‘scattergun’ approach to drug control would appear to be a waste of time. Instead, finely-tuned policies need to be drafted that target 13 specific kinds of drugs and specific kinds of users, and they need to do so in a way that avoids substitution to drugs and anti-social behaviours that may be as bad or even worse, than what the policy is trying to control. 14