rapport RESER SmGr (DOC, 805 kB)

advertisement

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

Research Report

Demand as a driving force of Service

Innovation

Research on the determinants of innovation linked to the local demand in

services, the international demand and the information and communication

technologies

Cristina Castro-Lucas,

Mbaye Fall Diallo,

Pierre-Yves Léo,

Marie-Christine Monnoyer,

Marina Figueiredo Moreira,

Jean Philippe,

Elaine Tavares,

Eduardo Raupp de Vargas

- January 2012 -

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

Abstract

This report presents the results of a research carried out to investigate the

relationship between the demand and service innovation in three dimensions: the

international demand, the public demand through public tender and the technological

demand through service linked to new products.. As different research teams have

worked on this project, the methods are not always the same.

Two of these teams have tested a theoretical model. The first one explains how firms

achieve international performance; the second one supposes that MICTs would

positively influence market and procedures innovation capabilities. The data used

were obtained by a specific survey answered by 51 top managers of business service

firms and analyzed by the Partial Least Square method. The third one realized a

study of multiple cases with ten analysis units conducted using semi-structured

interviews with professionals in the companies.

Some relationship could so be highlighted:

- As it is usually stated, service innovation plays a significant role in international

performance but far less than international experience. More upstream factors,

mainly the resources and capacities of the firm, exert also direct or indirect

influence.

- The ability of the firm to use ICT plays an interesting role as it simultaneously

helps international development and service innovation. Innovation appears also

to be enhanced by international competence of the firms’ personnel.

- Although MICT do not affect directly innovation capacities, they can influence

this variable trough the development of internal and market capabilities. This will

vary according to what type of mobile device is used.

- Innovations are identified in three steps: pre-sale, service providing, and postsale. It confirms the induction of innovations by governmental clients. Even though

this induction is not intentional, it meets the main trajectory presented in the

Chain-Linked Model.

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

1

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

Authors

Cristina Castro-Lucas,

M.Sc.

Marina Figuereido Moreira,

Post graduation in management,

University of Brasília, and

CERGAM-MI/Université Aix-Marseille III

15-19, allée Claude Forbin

13627 Aix-en-Provence cedex-1E-mail: cristinaclucas@yahoo.com.br

University of Brasília, UnB

Campus Darcy Ribeiro, ICC Norte, s. B1-576 - CEP:

70910-900 - Brasília - DF - Brasil

E-mail: marinafmoreira@terra.com.br

Mbaye Fall Diallo,

Ph.D, M.Sc.

Jean Philippe,

Ph.D., Management professor

CERGAM-MI/Université Aix-Marseille III

15-19, allée Claude Forbin

13627 Aix-en-Provence cedex-1

E-mail: mbayediallo2003@yahoo.fr

CERGAM-MI/Université Aix-Marseille III

15-19, allée Claude Forbin

13627 Aix-en-Provence cedex-1 –

E-mail : jean.philippe@univ-cezanne.fr

Pierre -Yves Léo,

Senior research fellow

Elaine Tavares,

Ph.D

CERGAM-MI/Université Aix-Marseille III

15-19, allée Claude Forbin

13627 Aix-en-Provence cedex-1 –

E-mail : pyl199@gmail.com

EBAPE/FGV

and CERGAM/Université Aix-Marseille III

15-19, allée Claude Forbin

13627 Aix-en-Provence cedex-1E-mail: elaine.tavares@fgv.br

Marie-Christine Monnoyer,

Ph.D, Management professor

Eduardo Raupp de Vargas,

Ph.D, Professor

CRM, Université Toulouse I Capitole, IAE

2 rue du Doyen Gabriel Marty31042 Toulouse

E-mail : marie-christine.monnoyer@univ-tlse1.fr

University of Brasília, UnB

Campus Darcy Ribeiro, ICC Norte, s. B1-576 - CEP:

70910-900 - Brasília - DF - Brasil

E-mail : ervargas@unb.br

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

2

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

3

Synopsis

Page

Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………........ 4

Chapter 1:

Business Service Innovation through Internationalization …………….......…………………… 13

1. Business service innovation and internationalization .................................................... 14

2. Key variables and theoretical model ………………………………………...……....... 18

3. Data analysis and results ............................................................................................... 22

4. Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 27

Chapter 2:

The Influence of Mobile ICT Use on Service Innovation Capabilities ……...……………….... 29

1. Theoretical Background ................................................................................................. 30

2. Model and hypothesis ..................................................................................................... 33

3. Results ............................................................................................................................ 35

4. Findings and Managerial Implications ……………………………………………….. 41

Chapter 3:

When the Government is the Market: Public Procurement and Innovation in Software Services 46

1. Innovation in services ..................................................................................................... 47

2. Innovations induction: public procurement in the Chain-Linked Model ....................... 49

3. Purchases for the innovation in software service .......................................................... 52

4. Method and cases results ............................................................................................... 53

5. Conclusions .................................................................................................................... 55

References .................................................................................................................................... 57

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

4

Introduction

In most developed countries innovation policies have been under critics for their weak

achievements: in France innovation is still a laggard policy; in Europe the Lisbon strategy is

considered as a failure apart for Sweden and Finland. Innovation policies are under scrutiny

because governments are reluctant to fund programs which are not dedicated to the satisfy

demands coming from consumers or from firms. Our research is in line with this stream of

thought looking at the determinants of innovation located in services offered with products or in

the service activities themselves, particularly under the influence of the international demand and

of the information and communication technologies facilities.

Service innovation has mainly been studied as resulting from R&D processes inside firms, or

ongoing transformations in the services offered. The role of demand, although recognized, has

never been thoroughly investigated. Our objective is precisely to establish the link between the

demand and service innovation which can be observed in three separate domains: the

international demand, the technological demand (through services linked to new products) and

the public demand through public tenders. The linkages between demand and innovation are

obvious when we observe firms behaviors: firms have to satisfy hard-to-please clients, private or

public, in a global competitive context. Our objective is to build and assess a model of

determinants to measure their relative impact on innovation. We need therefore to create a data

bank with a survey realized in France and ten Brazilian case studies. The four following points

will be now developed in order to introduce our report: the new innovation context service firms

are facing today, the necessity to establish a link between the numerous researches on service

innovation and the three domains of the demand we have identified, our research template and

lastly the methodology used.

1 - The new innovation context for service firms

Most developed countries have experienced a dramatic shift from goods to services: service is

now a dominant sector in terms of value added and employment. However, most analyses of

innovation still focus on goods and not on services. Therefore it is necessary to update our

research agenda to complete our knowledge on service innovation. To do so, we need to enlarge

our vision of innovation enabling us to take into consideration the role of demand.

This new approach has been resumed by the ‘Ten Types of Innovation’ model due to Larry

Keeley in the USA and reframed by the TEKES institute in Finland (2007). This model classifies

innovation into two main categories: the first one, ‘From the firm to market’ includes innovation

in the service process and in the service offering. The second category, ‘From the market to

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

5

firms’ includes financial and delivery aspects. These classes group together different elements.

As shown in table 1, the first category (From the firm to market) is similar to the traditional value

added analysis and is meant to identify the strategic advantages and competences of the firm.

Other innovations done to satisfy clients or to participate in networks to build external relations

constitute the second category (From the market to firm).

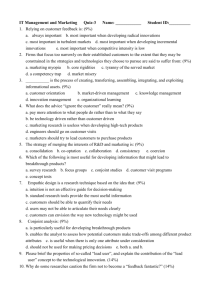

Table 1: The ‘Ten Types of Innovation’ classification

‘From Firm to Market’

PROCESS

Innovation process

Core process

1st Category:

How a company

organizes to

support innovation

2nd Category:

Proprietary

processes that

add value

Product/service

performance

Basic features,

performance, and

functionality

‘From Market to Firm’

DELIVERY

Channel

Brand

How to connect

your offering to

clients

How to express

your offering’s

benefit to

customers

OFFERING

Service system

Extended

system that

surround an

offering

Customer

service

How your

service

satisfies your

customers

FINANCE

Customer

experience

How to create

an overall

experience for

customers

Business model

Value networks

How the

enterprise makes

money

Enterprise structure

and value chain

Product-centered firms spend the majority of their innovation effort on product performance and

on the associated elements. Conversely, a lower emphasis is put on finance and delivery.

Empirical observation show that for service firms the ‘market to firms’ context is predominant

with innovations on the customer experience, valued networks, business model and brand.

The TEKES Institute’s analysis (2007) on US innovation during the 2005-2007 period shows a

certain number of key elements:

-

Customer is the new central point of innovation and has taken the place of competitors to

settle the overall strategy and the innovation strategy of firms.

Entrepreneurship is a driving force of innovation in service sector where the capitalistic

needs are less important than in manufacturing.

Most innovations are substitute for others tasks in the value chain.

Communication and information technologies play an essential role for service

innovation.

Others researches on innovation have identified the tendency to mix innovation in goods and in

services and the growing blurring of frontiers between the manufacturing sector and the service

sector, particularly for producer services. This is a locus of a debate between pure theory on

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

6

service innovation tenants and theory of assimilation of services to goods researcher. To go into

in this debate is out of our project but it is necessary to pinpoint that this context creates a real

difficulty for firm to assess service innovation value. As for innovation policy (Evangelista,

2006), we have to admit that there are only few public programs aimed to promote specifically

service innovation but all innovation policies admit the blurring of frontiers between goods and

services.

2 - Three domains in which innovation is linked to demand

As stated before, we identified three domains in which the demand from users or clients can exert

a driving force on service innovation: international development, mobile technology use and

governmental tenders.

2.1 - Service innovation and internationalization

In this research we will define and assess a theoretical model in order to identify and measure the

linkages between service innovation and internationalization. The contemporary

internationalization of firms is an economic context which generates a high pressure to innovate.

We propose to study the connections between innovation in service firms and their international

development. Innovation and internationalization have always been considered as two separate

axes for developing a firm. Bringing them together enables us to understand better, from the

conceptual and managerial point of view, the relationships which these two dynamics share.

Service innovation obviously has consequences for the international development of service

firms. But internationalization is also a powerful driver for service innovations and notably so in

business to business services.

Research on innovation in services has shown up the role of technical systems as a source of

innovation, but also the importance of innovations in methods and organization (Gallouj, 2002 &

2003). From a methodological perspective, these research works had to overcome analytical

difficulties specific to services due to the immaterial nature of their production, to their

interactivity and to the contribution of clients to the final outcome of the service delivery. These

works identified several types of innovation: radical, improvement, incremental, ad hoc,

recombination and formalization.

Also faced with a great variety of forms, research on service internationalization used a quite

similar approach. The first step was to describe the different types of internationalization: role

and type of international networks, solutions adopted to master the difficulty to keep high quality

standards in different cultural environments, use of information and communication technologies

(ICTs), replacing or simply supporting traditional networks, have been highlighted, and so have

the firm’s strategies concerning what service they offer abroad, but also how they organize their

relations with clients.

The connection between innovation and internationalization becomes evident when observing the

business world: globalization is the rule, whether it is commanded by markets or competition.

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

7

Business to business services must satisfy increasingly “worldwide” clients by tackling

international competition stirred by the generalization of deregulation policies. In such a context,

the ability to master the running costs becomes essential and is often supported by innovation in

methods but is reinforced by growing internationalization, which may well entail some scale

economies (Ghemawat, 2007). The search to standardize offers is a very similar process. The

quest for reducing costs is a tendency which remains fundamental for firms, but some changes in

the market can provoke more basic innovations. New countries are emerging on the world’s

economic scene, and expectations for better adapted, more “localized” offers can be observed. A

new dialectic may therefore exist, inducing more radical innovations to be implemented.

Our contribution intends to analyze the relationships between these drivers of the transformation

of firms and offers, to distinguish clear profiles and specific contexts and draw up the managerial

implications from them.

2.2 - New mobile technologies and service innovation

In order to achieve flexibility, many companies adopt information and communication

technologies that support mobility, context and location-awareness as well as networking. Mobile

information and communication technology (MICT) includes technological infrastructure for

connectivity such as Wireless Application Protocol (WAP), Bluetooth, 3G and General Packet

Radio Service (GPRS), as well as mobile information appliances such as agendas, smart phones,

mobile telephones, notebooks and tablet PC (Nah et al., 2005).

By extending the use of computers and the Internet into the wireless medium, mobile technology

allows users to have at anytime and anywhere access to information and applications. This

provides greater flexibility in communication, collaboration and information sharing (Sheng et

al., 2005; Chen & Nath, 2008). These environments facilitate access to enterprise resource

planning systems and to productivity tools, such as email and scheduling (Cousins & Robey,

2005). The organizations that operate in these environment not only provide their employees with

nomadic computing capabilities, but they also design their business processes, operational

procedures, organizational structure, and reward systems around the needs of nomads (Chen &

Nath, 2008).

This can result in the gradual improvement of existing working practices, enabling, for example,

efficiency gains and flexibility. However, mobile IT also has the potential of being a disruptive

technology, supporting a transformation of the way decisions are made, innovations carried out or

services delivered (Sørensen et al., 2008). This disruptive technology may offer changes in the

organizational process for many tasks (Boutary & Monnoyer, 2008).

In other words, mobile information technology in general will play a significant role in

organizational efforts to innovate current practices. Enterprise mobility signals new ways of

managing how people work together using mobile information technology and will form an

integral part of the efforts to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of information work

(Sørensen et al., 2008; Alonso et al., 2010; Zhang, 2011). The rapid pace of adoption and

advancement of mobile technology also creates opportunities for new and innovative services

provided through mobile devices (Sheng et al., 2005).

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

8

2.3 - Service innovation and governmental demands

Using its purchasing capacity directed to innovations contractions, the State plays the role of a

consumer capable of establishing purchase requirements which will impact on the products and

services contracted. It is believed that they lead to innovative solutions. It means: to induce the

generation of innovative products and services in the suppliers. The role of the State would then

be the one to effectively define the requisites and parameters of the public purchasing capable of

inducing the generation of innovations in the suppliers.

In 2004, Brazil formulated its own Policy for Technology, Industry, and Foreign Commerce,

which has the support to innovation as one of its goals and set some strategic sectors. Software

production is one of the target sectors, being considered as the sector that most improved

regarding Brazilian Information Technology Industry. In 2008, Brazilian government announced

the use of public procurement as a priority tool to impulse the economy, inserting information

science sector among the most supported ones. It seems to us it was a quite interesting

opportunity to focus on this activity, to analyze the link between public demand and innovation.

3. - Research template

Our general approach is a conceptual and exploratory one.

We have already conducted two surveys to better understand service firms’ internationalization

(Philippe & Léo, 2010). A systematic survey of scientific publications issued between 2005 and

2011 which were simultaneously dealing with service innovation and internationalization was

then realized. Concerning ICT and service firms’ organization, some previous researches had

been done (Monnoyer et Omrane, 2003; Monnoyer & Madrid, 2007; Boutary & Monnoyer,

2008). However, most papers are not focused on mobile technologies, which seem to have

particularities associated to the nomadic computing capabilities. A first exploratory survey was

then conducted on a ten firms sample size, dealing with these two subjects.

This survey allows some preliminary findings that we can sum up as followed:

-

Service innovation is often perceived as an antecedent factor of internationalization

The design of innovation is an application of the knowledge of entrepreneurs

Professional standards have a positive impact on firms performance

Innovation and internationalization need a networking support process

Innovation does not solve international contact constraints and international dynamism

seems to be better when the network is built with subsidiaries

ICT offer powerful means to guarantee the service quality,

The appropriation of MICT depends on how strong the user is embedded in his or her

responsibilities.

This constitutes a preliminary set of hypothesis on the entrepreneur behavior, the innovation

process performance linked to internationalization, the link between innovation and R & D, the

role of networks in the internationalization process, the joint benefits brought by innovation and

internationalization and the benefits brought by the ICT to sale or deliver services in foreign

markets. A quantitative systematic survey with a questionnaire was passed to 807 managers of

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

9

service firms (Altares data base) to confirm our hypotheses about the relationship between

innovation and internationalization, and about the influence of mobile ICT on service innovation

capabilities. The interviewed managers were selected in the data base according to the firm’s

main activity and its international development as it could be anticipated by some indicators

given in the Altares data base. The questionnaire and the method we used are presented in detail

below (4.1).

The link between public demand and innovation in services firms has not been largely studied

until now, as shown by our literature review. So we will propose a development of the model

proposed by Kline and Rosenberg (1986). We conducted a descriptive qualitative study based on

multiple cases in order to assess whether and how far the requirements set of public procurement

induce innovations in software enterprises. Ten cases of software enterprises supplying the

federal government were extensively analyzed. They were selected according to the main activity

of the firm which had to be in software services and also to the dedication of these firms in

supplying software services solutions to the federal government.

The data collection was conducted through a two step survey. Firstly, a semi-structured

exploratory survey conducted by a government official in charge of the software department –

from its application, data have been collected on the innovation process of the enterprises, in

which the types of innovation are considered as well as the time they had happened. This

interview was conducted aiming to reassure the construction of the second instrument, which

consists of a semi-structured interview guide applied to professionals with three profiles in the

selected cases: in charge of the preparation and participation of the enterprises in the processes of

public tender for government supply, professionals with a technical profile for software services

providing, and professionals in charge of ongoing project management. Afterwards, the aim is to

identify the rising of innovation at these three different stages of the software service delivery to

the federal government: pre sale, service providing, and post sale.

4. Statistical methodology

4.1- Questionnaire, survey and sample

The questionnaire was set up in order to obtain the needed information and the meanings from

firms’ head manager after a 10-12 minutes phone interview. It was organized into two main parts:

the first one aims at describing and measuring the innovation in service activity, and the second

one at evaluating the international development, performance and assets. In order to comply with

the short time of interview, very few questions had free answers. Thus the questionnaire was first

submitted to a small sample of people in order to test and verify if every questions were similarly

understand and easy to answer. Most of the questions were designed in such a way that the

responding person had to give her/his assessment on a five points Likert scale. As much as

possible, the wording of items refers to those already used and tested by previous studies on

innovation and international development that were found in the literature survey.

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

10

A sampling list was set up with the intention of pre-selecting French business service firms which

had already developed markets abroad. According to these criteria, we selected in the “Altares”

data base around 2000 firms but this number falls to 1025 firms truly belonging to the business

service sector; among them, some were not suitable for our questionnaire, whether because they

are specialized subsidiaries of very large corporations, providing services mainly inside these

organizations or, on the opposite, very small firms with less than 5 employees with highly limited

organizational capabilities. A few more had to be dropped from the phoning list, due to missing

phone numbers which couldn’t be found on the Internet websites. Lastly, the operational list

sums up to 807 firms which were systematically contacted by phone by professional interviewers

(Mars-Marketing, Marseille) during the months of May and June 2011.

361 responses were obtained, amongst which surprisingly 271 answered they didn’t export any

service and 38 others claiming no international activity at all. One answer had also to be deleted

as it contained too many missing values. This left only 51 responses from business service firms

which were exploitable for our study; this 6 percent answering rate is clearly a low one that can

be attributed to the need we had of getting answers from the top managers. The high number of

the answers claiming to be out of the target can indeed be considered as a pretext given by

overbooked managers to definitely avoid the interview. If not, it would mean that the commonly

used “Altares” data base is of poor quality, as far as service firms are concerned.

Nevertheless, these answers can be usefully analyzed, even if any generalization of the observed

results should be done very cautiously. As shown in table 1 the responding firms do belong to

two main kinds of activities: logistical services and engineering consultancy. It is worth to

observe that amongst the hundred of software industry firms contacted only two gave a complete

answer. Almost no management consulting firm answered our questionnaire as didn’t also

operational services or research enterprises. Moreover, when considering what services are

mainly sold abroad by the respondents, the sample splits simply into two parts: logistic services

or technical studies.

29 firms (57 percent) which answered our questionnaire are independent and among the 22

others, which are belonging to larger organizations, only 12 are subsidiaries of very large

corporations. Thus, most managers interviewed have full authority on their enterprise which

remains small or medium sized: 27 ranging from 10 up to 70 employees, six between 100 and

200 and six others, very small with only six or seven employees. All these firms are widely

spread over the national territory, 15 being located in the main French region around Paris, the

other 36 in most of the 21 French regions, with a maximum of 5 in the Marseille-Nice region.

Due to its rather small size, this sample deserves to be more precisely described. These service

firms have been opened to international markets for long and therefore benefit from a long lasting

international experience: only one has begun that strategy less than five years ago, five between

five and 10 years. The remaining are 11 with a 10 to 15 years experience, 13 with a 15 to 25

years one and for 21 the experience is even longer. As we have already observed with other

exporting business service firms samples (Léo et al., 2006), the use of a delivery network abroad

is a choice that takes time. Effectively, only a minority (17) has not yet developed any delivery

network abroad. 82 percent of the 34 others have built their international network with

subsidiaries (or at least one). This is remarkable for these rather small firms because a subsidiary

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

11

appears to be the most expensive kind of outlet, even if it is probably the best suited for service

firms (Philippe & Léo, 2010).

Table 2: The sample’s main characteristics

Sampling list %

Main activity:

Logistics & transport

137

17.0

Computer software

103

12.8

Engineering

274

33.9

Research

46

5.7

Management consulting 156

19.3

Operational services

91

11.3

Size & category of firm:

Large corporation subsidiaries

Small or medium size groups

Medium size firms (100-200)

Small firms (10-70)

Very small firms (6-7)

Location:

Ile de France (Paris)

357

44.2

Extended Parisian basin

56

6.9

South (PACA, Languedoc) 73

9.0

South West

62

7.7

North West

61

7.6

North East

78

9.7

Centre

117

14.5

Other (overseas)

3

0.4

Total

807 100.0

Answers obtained %

28

2

19

1

1

2

54.9

3.9

37.3

2.0

2.0

3.9

12

10

6

17

6

23.5

19.6

11.8

33.3

11.8

15

8

8

4

5

6

4

1

51

29.4

15.7

15.7

7.8

9.8

11.8

7.8

2.0

100.0

answer rate (%)

20.4

1.9

6.9

2.2

0.6

2.2

4.2

14.2

11.0

6.5

8.2

7.7

3.4

33.3

6.3

Answering firms show a rather high international involvement: according to their evaluations, the

mean share of international turnover (that is the firm’s exports plus the turn over of foreign

subsidiaries) in the total turnover (firm’s turnover plus foreign subsidiaries’ one) reaches 66

percent for the 50 firms having given these data. 10 do not have any domestic turnover and are

therefore totally specialized in international service delivery. 14 others have a similar

involvement with international turnover ratios between 80 and 99 percent. Less involved on

international markets, 13 have nevertheless ratios from 50 to 75 percent and 10 others from 20 to

45 percent, which remain fairly honorific scores. Only 3 firms rank far behind with 5 to 10

percent of general turnover obtained from foreign markets. The same very internationalized

profile is obtained with the number of countries where international sales are obtained: 16

countries on average but 10 for the median, a score less influenced by possible outliers: this

describes a sample of service firms widely open to international development. 12 have a very

large geographic extent with 20 up to 60 countries, 17 have between 10 and 15, 8 between 5 and

8 foreign countries. The remaining 9 show a limited extent, most of them being however in 3 or 4

foreign countries.

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

12

4.2- The PLS modeling tool

The use of structural equations modeling allows studying relations between variables which are

not directly observable. Several methods are used to generate structural equations, however PLS

has been acknowledged to be a robust one (Chin, 1998). Its algorithm is rather simple to

understand and requires a very limited number of probabilistic assumptions. PLS does not need a

large size of the sample and can also accept a small number of scales of measurement. Due to the

exploratory context of this research and to the limited size of the sample which counts only 51

respondents, the PLS was a well appropriate technique to analyze the data. Partial least squared

(PLS) path modeling is a multivariate technique to test structural relationships and a general

method to estimate models with latent variables measured by many items. This tool has as a main

objective, the causal predictive analysis when problems are complex and the theoretical support

is very limited (Wold, 1982). It is now used by a growing number of researchers from various

disciplines such as strategic management, management information systems, marketing, etc.

(Henseler et al., 2009).

Basically, the objective of the PLS modeling is to predict dependent variables, latent or manifest,

maximizing the Explained Variance (R²) of the dependent variables. The PLS method differs

from models based on Structure Equation Modeling according to the optimization method which

depends on the pursued objectives. The PLS is more suitable to predictive applications and theory

development (Exploratory Analysis) while SEM methods are more suitable to confirmatory

analysis (Lévy-Mangin & Varela-Mallo, 2006). Besides, the PLS doesn’t require any parametric

conditions, so this technique is particularly appropriate in the case of small samples with nonnormal data (Chin, 1998. Vinzi et al., 2010). In spite of the limited size of the sample, we can

evaluate the quality of the model’s estimates by using the bootstrap process: we launched 1000

bootstrap samples based on the 51 cases and calculated the Student’s T for the coefficients

associated to each relationship taken into account by the model.

5. – Plan of the report

Three domains have been selected as potentially interesting for the questions we investigated:

international development, mobile technology use and governmental tenders. The results

obtained in each one of these three domains will be extensively presented in each of the three

chapters of the present report.

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

13

Chapter 1

Business Service Innovation through Internationalization

Cristina CASTRO-LUCAS

Mbaye Fall DIALLO

Pierre-Yves LEO

Jean PHILIPPE

Many research found innovation, and more specifically product innovation, to be an important

factor in explaining the entry and success in the export markets: successful innovation may push

productivity or help to find a greater demand in foreign countries. We intend to test the

relationship between innovation and international performance, assess the impact of innovation

compared to international specific resources; in others words study the combination of innovation

and international capacity to explain the performance on international markets. But, as we are

dealing with services, we can also consider the internationalization process as a powerful driver

of innovation for the service firm. We also have to consider the impact that may have the

Information and communication technologies (ICT) which are of paramount importance for

services and may influence simultaneously the firm’s innovation and its international

performance.

Service innovation has mainly been studied as a resulting process of R&D, or ongoing

transformation in service offer. The role of internationalization in the adaptation of service,

although recognized, has never been thoroughly investigated. On international markets, service

firms have a priori the choice between two main alternatives: they can either adapt their service

or standardize it. Adapting a service is a natural way to cope with the differences between a local

foreign context and the domestic market; a correctly adapted service will be more easily

assimilated and accepted by foreign clients. On the opposite, standardization often compels the

firm to redefine its core service concept even on its home market; but a standardized service will

significantly facilitate further international development with a better remote control of the

homogeneity and quality of the services delivered. Consequently, internationalization makes

firms come to terms with options of innovation which are obviously strategic as they directly

affect the firm’s offer. Of course, these options may also depend on the type of service activity

and on other strategic variables such as the type of organization chosen to develop abroad or the

experience acquired on foreign markets. The positive association between exporting and

performance increase has been explained by learning-by-exporting, selection mechanism in favor

of the more international firms, but has been rarely explained by a systematic innovation policy,

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

14

and the mix of innovation and international strategies. Our objective proposes first to explain

service innovation by technological, organizational, relational, ICT and expertise capacities.

Service innovation mainly gives the firm a service advantage which may generate international

performance. Moreover another factor, namely the international experience, can also explain the

international performance. International experience produces mainly marketing advantages in the

foreign markets and is driven by international organization capacity and international staff

specific knowledge. According to our hypothesis, learning-by-exporting should also impact the

firm’s service innovation. This study is conducted within the framework of the resource-based

theory.

Our objective is to build and assess a model of determinants including innovation to measure

their relative impact on international performance. This chapter proceeds as follows. We will

investigate first what conceptual framework can be used to deal with the specific problems

arising when analyzing the linkages between service innovation and internationalization. The

second part describes the key variables and the theoretical model. The third section provides the

results of the empirical analysis presented in the introduction and discusses the main findings as

well as the conclusions and the managerial implications that can be drawn.

1 - Business service innovation and internationalization

The connection between innovation and internationalization becomes evident when observing the

business world: business to business services must satisfy increasingly “worldwide” clients or

“domestic” client demanding world prices stirred by international competition. In such a context,

the quest for lower costs is often supported by innovation in methods but is reinforced by the

growing internationalization, which may well entail some scale economies (Ghemawat, 2007).

The search to standardize offers is a very similar process. The quest for reducing costs is a

tendency which remains fundamental for firms, but the changes in the market can provoke more

basic innovations. New countries are emerging on the world’s economic scene, and expectations

for better adapted, more “localized” offers can be observed. A new dialectic may therefore exist,

inducing more radical innovations to be implemented.

Our contribution intends to analyze the relationships between these drivers of the transformation

of firms. In manufacturing, product innovation has been recognized as a powerful tool to enter

international market. Vernon (1966, 1979) has proposed a framework for the internationalization

process of product and firms based on product innovation. The sequential process of the product

life cycle starts from home-based product innovation to gradually reach export markets and

eventually foreign direct investments. Exports bring increasing sales, contributing to the

spreading of innovation costs. There is also the possibility of learning-by-exporting: exporters

gain greater ability to adapt to changing markets, (Salomon & Shaver, 2005), to adopt new

production technologies and enhance productivity (Cassiman & Golovko, 2011). For goods, there

is still a debate about the impact of product and process innovation on productivity (Griffith et

al., 2006), but recent studies seem to acknowledge a larger effect of product than process

innovation on firm productivity and performance.

In service analysis, we don’t have reached yet such a complete view of the question. Service

innovation analysis is developing in complexity and thoroughness since Barras (1986) inversed

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

15

product life-cycle model and Soete & Miozzo’s (1990) technological trajectories. Innovation in

services is strongly linked to technology and in particular to ICT. Barras’ model describes a

sequence of transformation for services which is the opposite of the traditional cycle of

innovation for production in the manufacturing industry. The cycle starts in the back office with a

phase of incremental innovations on methods (computerization of procedures, for example),

continues in the front office with a phase of radical methodological innovations (for example,

installation of automatic cash machines by banks) and ends up with “product” innovation, when

the firm is able to propose new services to its clients. This analysis shows that service innovations

are not situated in the technical systems themselves, but in the changes which are made possible

by them. The main criticism on this model, as expressed by Faïz Gallouj (1994, 2003) or by

Camal and Faïz Gallouj (1996) is that it tends rather to represent a diffusion model for technical

innovation originating from industry into services, more than a real theory on service innovation.

In particular, it does not take into account non-technological service innovations, for example

organizational ones.

Barras’ model is completed by the taxonomy of service sector technological trajectories which

isolate three kinds of activities: low innovation activities which are dominated by technology

suppliers; they can be found in services to persons sectors and in public or social services.

Network services whose overriding strategy of lowering networks’ running costs imposes upon

technology suppliers, specifications adapted to their organization. The third category concerns

knowledge intensive services with an offer founded on science; in this case, firms may be highly

innovative and they may well demand that their suppliers meet their very specific needs. This

taxonomy underlines the heterogeneous behavior of services property but it presents some

weaknesses pointed out by the analysts of service innovation: the concept of trajectories seems to

be too deterministic and univocal, excluding the possibility for a firm to belong simultaneously to

two of them. Otherwise, as with Barras’ model, non-technological trajectories are clearly omitted.

In his research on service innovation theory, Gallouj (2002) proposes a representation of service

as the simultaneous mobilization of technical characteristics (material or immaterial) and internal

(the provider) or external (the client) skills, to produce a service with clearly defined

characteristics. Then he defines innovation as being any change affecting one or several terms of

one or several vectors of these characteristics (technical, service) or skills. The forms of change

are manifold: evolution or variation, extinction, emergence, association, dissociation, formatting.

Innovation is not considered as a result, but as a process leading to “modes” which may be

described by the particular dynamics of characteristics. Radical innovation can be observed when

a new set of characteristics is created; improvement innovation, when the “weight” of certain

characteristics is increased; incremental innovation operates by adding or suppressing

characteristics, but maintaining the general structure; ad hoc innovation consists in offering an

original solution for a specific problem, modifying the skills and technical characteristics; a “recombining” innovation keeps the characteristics and skills unchanged but associates and/or

dissociates some of them differently; and lastly formalization innovation aims at better quality

control but it also reduces the flexibility of the organization by formatting and standardizing the

characteristics.

This representation of services as vectors of skills and characteristics can be applied to any major

questions concerning service dynamics and notably to internationalization, which is going to

affect certain characteristics of the offer. Unfortunately, the Gallouj’s model of service

innovation remains silent about the question of the hierarchy of forces which can generate

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

16

innovation: is it R & D, innovative capacity of the personnel, its competence, organizational

capacity of the firm or its relational capacity that makes work together all the elements of the firm

in order to bring about service innovation? We don’t know which one has the leading influence

on the firm performance.

In a sense, according to Gallouj’s definition, internationalization could be considered as a specific

case of innovation. But such an interpretation would be far too reducing because

internationalization is not only an innovation for the firm: it has direct and relatively rapid

consequences in terms of turnover, operations, costs and benefits (Farrell, 2004. Gottfredson et

al., 2005). The main difference with innovation lies in the extent of changes, probably more

limited in the case of internationalization because of the quest to cut costs and the risk associated

with new markets. Välinkangas and Lethinen (1994) identified three main strategic axes for

international development: standardization, specialization and customization. Standardization

resides in the pursuit of scale economies, aiming the service at the widest ranging market

possible. With specialization the firm seeks to take advantage of one single and unique service,

totally differentiated from those of competitors. Customization is akin to adaptation. Analyzing

the dominant strategy, Philippe and Léo (2010) find that most internationalized business firms

associate two different approaches: on the one hand, they are trying to be closer to their clients,

by offering customized services to each kind of circumstance, which leads them to widen their

range of offers. On the other hand, they seek internal efficiency by the improvement of their

procedures and often by quality certification.

Within the development strategies of firms, internationalization and innovation occupy the front

line, sometimes in a complementary manner because the two strategies have identical elements in

common: creativity, growth, but also risk. However, the two strategies are rarely conducted

together by firms because each one is increasing the diversification which comes up against the

knowledge system of the management and the dominant logic of resource allocation (Prahalad &

Bettis, 1986). We have conducted a systematic survey of scientific publications on service

innovation and internationalization and issued between 2005 and 2011(databases used: ABI /

Inform Global (ProQuest), Emerald, JSTOR, Sage Journals Online, EBSCO, Oxford Journals,

SciELO and Redalyc ). This search pointed out that, in spite of numerous research works

conducted and published on the two fields taken separately, very few had been conducted on the

possible relationships between these two strategies as far as service firms are concerned. Only

few articles could be identified as paving the way for our own research.

Most of the selected research works are essentially aimed to examine how the internationalization

process contributes (either directly or indirectly) to the development of innovations in service

companies. They stress the importance of relations within established networks. Other articles

investigate the impact of firm performance by examining the contribution of formal and informal

innovation in services through the concept of strategy. Some other texts try to assess needs of

internationalization as a process of acquiring and transmitting knowledge from the investment of

resources.

Frenz et al. (2005) aimed to identify the relationship between internationalized companies and

the propensity to innovate. They first observed that it was mainly the case for firms operating as a

group. To belong to a group leads to a greater potential for innovation, since each part of the

group learns about the environment in which it operates and may transmit this knowledge within

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

17

the whole group (Zanfei, 2000). More interesting for our problematic, they observed that other

companies have the opportunity to learn from different innovation systems and cultures, when

they are operating in different countries, thus impacting positively their innovation potential. A

similar survey was conducted by Lavie and Miller (2008) which focused on the structural and

relational aspects of organizational networks, looking at their immediate impact on the

performance of the firm. This relationship is attributed by the authors as effects of a learning-bydevelopment process.

Meliá et al. (2010) have collected data from small and medium service companies in the

perspective of international entrepreneurship. They intend to demonstrate that the innovation

approach speeds up production time: firms that internationalize can perform more activities and

choose to control modes of entry into foreign markets. The results presented by these authors

suggest that two different models of internationalization can be found within the service sector: a

gradual one and a far more rapid one. The study by Peng et al. (2008) discusses the idea of

institution-based international strategy, positioning itself as one of the feet that help sustain the

"tripod" of organizational strategy (the two others being the industry and the resources invested).

According to the authors, this tripod provides new strategies and allows firm performance.

Racic et al. (2008) explore the main processes and determinants of the internationalization of

Small and Medium Enterprises (SME’s) in Croatia and analyze the data obtained through the

SME Exporters Survey for the period between 1999 and 2004. They examine the growth

strategies of SME’s, emphasizing factors such as innovation and export orientation, which is

partially supported by the results presented in the survey. The authors observe that the "ideal

type" of a Croatian export-oriented SME tend to operate in medium and high-tech industry or in

services, with specific market niches. As such, this research illustrates the classical relationship

identified between innovation and export, the first being a driver for the second, even for service

activities.

Park & Mezias (2005), wanted to see how the dramatic changes in the availability of resources in

the sector had affected the stock exchange evaluation of inter-firm alliances. From a survey of 75

e-commerce companies in the period 1995-2001, they noted that the stock market had responded

more favorably when alliances had been concluded during a less generous period. This research

work stress the importance that may take the environmental context for strategies of firms

involved in highly innovative and internationalized sectors.

Nachum and Zaheer (2005) focused on the resource availability of the service sector, in order to

understand why companies settle abroad even when technology allows easily trading at a

distance. The authors note that the cost of distance is differentially perceived by firms. Search for

knowledge or quest for efficiency are identified as the two most important factors taken into

account by service firms, when choosing their entry modes in foreign markets. On the one hand,

they are seeking to establish export platforms with low investment of organizational resources,

and on the other one, they are trying to gain knowledge from the variety of environments offered

by international settlements.

Martinez-Gomez et al. (2010) relate the research works focusing on networks with the ones

focusing on strategies. They intend to understand the relationship between globalization or

internationalization strategies and the dependence of knowledge intensive service firms on

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

18

innovation networks. Thus, they highlight the characteristics of internationalized companies

seeking innovative actions.

The articles collected in this study help to bring more evidence to the characteristics of field

studies on the relationship between internationalization and innovation in services. One of the

limitations common in the reviewed studies relates to the lack of statistical validation of the

questionnaires used. Although only a few articles have adopted a tool for data collection, these

were not validated. Few articles detailed the adoption of methodological care in formulating the

items of the survey instrument used. Another common limitation in these research works

concerns the fact that the authors based their surveys mainly in networking concepts, strategy and

resources. They seem to have overlooked other aspects that can determine the relevance of the

relationship between innovation and international development, such as learning theory, or

behavioral theory, which try to explain some factors of the managers’ motivation. Moreover,

these research works seem to have limited themselves to the identification of competencies to

address this important relationship. In this sense, these texts state that innovation is the main

initial process for internationalization of continuously innovating companies. This statement is

mostly backed by three theoretical approaches: networking, strategy and resources (material or

immaterial).

This relationship can also be analyzed as a feedback process: operating in different countries,

may create constant stimuli to the process of innovation in service companies. For example, the

opening of new markets generates more diversity in business activity which has to deal with a

new economic and cultural context: new processes, new ways to contact clients, etc. have to be

set up and this feeds cyclically future innovation. Thus, the knowledge acquired by the company

that goes international often entails a reformulation of the use of resources and services which in

turn enhances its innovative actions.

2 - Key variables and theoretical model

As said before, we have already conducted surveys on the subject of innovation and

internationalization (Philippe & Léo, 2010). We have drawn from them a certain number of

conclusions which constitute the basis of our present survey. First of all, we found that a fair

proportion of exporting firms declare having a R & D department but this one, strictly speaking,

doesn’t work on the renewal of the service concept which is offered to the client or on the

technology used to deliver quality services. The main domains of innovation which are developed

concern procedures and relations. Innovative exporters present a specific competitiveness profile

which can be distinguished from non-innovative exporters. Search for quality is certainly among

their first preoccupations. The second important lever is the manpower skills: It is evident that the

impact of a service firm depends first and foremost on this factor associated to its workforce, but

also to the technology they are able to use.

According to the common idea, innovative service firms developing abroad should better perform

on international markets and this has to be verified. Thus, international performance is the

variable this research tries to explain. The first question that rises is to define what international

performance is and how it can be measured. Most of the numerous studies that have given their

specific answers to this problem were developed in the context of exporting small or medium

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

19

sized firms and have been extensively analyzed by Luong (2009). Generally speaking,

performance can be evaluated according to two separate approaches, either by calculating ratios

based on the firm’s accounts or by asking its own assessment to the top management. As anyone

could expect, the two measures appear to be quite well correlated in Luong’s sample but

unfortunately not enough to be synthesized in a single latent variable. Actually, the first method

should give unbiased evaluations but they don’t take into account the achievement of the

objectives set up by the management (Diamantopoulos & Kakkos, 2007).

Moreover service activities’ performance on international markets is rather hard to calculate

because some firms have set up subsidiaries abroad when other are simply exporting; many

intermediate situations can also be observed that should entail specific calculations (Léo &

Philippe, 2011). In the limited time of a phone interview, the manager’s assessment is probably

the best evaluation that can be obtained on how the firm is performing on international markets.

As for any measure constructed from an expressed opinion, that question was asked in different

terms in order to let emerge a latent variable: firstly his global satisfaction about the results

obtained by his firm on the international markets since the last three years (answer on a five

levels scale varying from highly dissatisfied to highly satisfied); then the same question was

asked from different specific points of view: growth of international sales, profitability of

international activities, international market shares, geographical expansion (number of market

countries) and steadiness of international turnover.

According to the resources based theory, international performance depends on specific resources

that are more or less available to service firms. Two of them have appeared to us particularly

sensible for service firms as their core competence is narrowly tied to the human resource: the

international competence of the staff on the one hand and on the other the international

experience obtained from long lasting involvement in foreign countries. The human competence

of the staff dealing with the very various environments encountered at international level was

assessed by the managers which were asked to select an answer on a five point scale (from “no

specific competence” to “excellent competence”). Five domains of competence were proposed:

Foreign rules, regulation and legislation; Commercial ways and customs in common use in

foreign countries; Culture and civilization of foreign countries; Administrative and technical

aspects which are compulsory for international trade; Foreign language knowledge and mastery.

As observed by many authors (Laghzaoui, 2009) the international experience acquired by the

firm is poorly evaluated by the geographical extent, the variety and the duration of its

international development. We tried to measure it through direct questions asked at the end of the

interview: three sentences (that can be found in appendix) were proposed to the manager who had

to express his degree of agreement on a five points Likert’s scale.

Our literature survey has shown that service companies may choose different ways to conduct

their innovative actions and will attain different levels in these processes. Measuring how far a

firm is innovative is a real difficulty and the previous studies often choose upstream indicators

such as availability of R & D department, importance of R & D expenses, patents or downstream

ones such as the share of new products in total sales. These indicators have been severely

criticized and the problem is increasing when dealing with service innovation which has been

very broadly defined in Gallouj’s approach (2002).

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

20

In this study, we have chosen to evaluate service innovation by the intensity of the changes

having been accomplished during the last three years according to eight different dimensions of

the service activity: The internal procedures set up to perform the service; The way the service is

made available for clients; The service business model; The legal environment of the services

(brand, labels, certifications); The technology used to accomplish the service (soft or hardware);

The main kind of clients that is targeted; The content of main services offered; and the content of

peripheral associated services. These items are based on the classification of the innovation types

proposed by Tidd et al. (2008) and the last two refer to Eiglier’s proposal (2004) to distinguish

radical innovations (affecting the core service) from incremental ones (concerning the associated

peripheral services). As Barras’ model had highlighted the importance of technology as main

driver of service innovation we also asked how the firm could be positioned in respect to its main

competitors from the technological point of view: backward, ahead or at the same level. It was

also asked what share of the general turnover was obtained by recently (i.e. since three years)

developed service activities; the answers were converted into a 5 levels scale.

In order to explain the innovation intensity we refer to the resource and competence theory and

try to measure the firm’s capacities acquired in different fields that can be considered as drivers

for the innovative process. The mainstream of service innovation studies points out the R & D

department as the main driving force of innovation in service firms. Thus we consider first the

capacities that the firm may have in this domain. The managers were asked to assess the

efficiency of their organization and of their personnel from the innovation capability point of

view on a five point scale. The five items are presented in appendix. Research works on

innovation also highlight the prominent role played by fluent communication either within the

firm or between the firm and its external stakeholders (clients, suppliers, partners, consulting

advisers, and even with possible competitors). Therefore questions were asked in order to

measure what could be designed as the relational capability of the firm: five items were so

proposed, according to the same frame as the previous ones. They can also be found in the

appendix. As far as services are concerned, there is another capacity that should play an

important role in innovation as well as in international performance: the capacity of a firm to use

ICT for various purposes. This capacity is obviously tied with the relational capability but it also

entails the mastering of a technology which may generate new services, new delivery modes and

as such it should be also a driver for service innovation.

Thus, we propose the following theoretical model which should allow well to assess the different

ways that takes the relationship between service innovation and internationalization. The main

hypothesis of this research and the theoretical model, illustrated in figure 1, is that service

innovation impacts international performance. The works of Bartlett and Ghoshal (1990) and,

more recently, those of Jeong (2003) clearly highlight that the relationship between innovation

and internationalization represents a strategic focus for the firms. Dib (2008) in his studies reports

that companies with greater capacity for innovation than their competitors (evaluated by R & D

expenditures on total expenditures) tend to follow an international trajectory. This statement

clarifies the first hypothesis of this study (H 1): innovation should exert a positive influence on

the international performance of service companies. These authors also show that the entry into

new markets may induce incremental innovation strategies as well as more radical ones. This

“feedback” relationship is taken into account by the second main hypothesis of the model (H 2).

It states that international competences acquired throughout the internationalization process exert

a positive influence on service innovations.

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

21

Figure 1: The theoretical model

R&D capability

(organizational)

H3

Service

innovation

H4

H1

Relational

capability

H6

International

performance

H5

H7

ICT capability

H2

H8

H 10

International

competence

H9

International

experience

As Dosi (1988) points out, innovation is increasingly based on science, R&D and new products

are more knowledge-intensive. New innovations are demanding more specialized knowledge

which becomes more complex and fragmented. Firms with employees able to master the newest

technology (whether it is in the software or in the hardware domains) hold a technological

advantage on others. Nevertheless they have to set up organizational means, as an R&D

department, in order to put their innovative capacities in a concrete form. Thus, our third

hypothesis (H 3) states that R&D capacity is positively tied with service innovation.

For McGee et al. (1995) the relationship within organizational networks, increasingly levers up

the technological potential of companies, because partners and cooperative activities contribute to

the competitive advantage of firms. According to Fleury & Fleury (2003), these new

organizational networks, are associated with an increased globalization of firms which position

themselves in these new international inter-organizational networks. Thus, Freeman (1991)

explains that innovation results from the combination of different kinds of networks: internal

ones (communication and integration of activities between departments) but also external

networks (with universities, consumers, professionals, other organizations, etc.); these networks

may be highly formal or totally informal according to each situation and what is judged as the

most suitable by the promoters. Nevertheless the usefulness of these networks depends on the

capacity of the firm to well communicate within these networks. Therefore the relational capacity

of a company should positively influence his service innovations (H 4).

The capacity to use ICT plays a very peculiar role in this model. It probably impacts the

relational capacity, inferring that the ICT does not reduce costs in acquiring information and

knowledge, but they generate for the organization new resources from networks cooperation or

strategic alliances (H 5). The dynamic power of this new technology for services explains that we

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

22

add another hypothesis (H 6) stating that ICT capability should directly impact service

innovation. According to Kon (2006, p. 53), the impact of competitive pressures imposed by the

reformulation of organizations, aimed at a new production process and organizational

information service and communication, “leads for the service sector, as well as for other

sectors, to labour productivity and capital growth”, having a direct relationship with firm

performance. In this research, we propose the (H7) hypothesis that capacity of ICT use has a

direct relationship, with the international performance in service companies.

The bottom part of the model as shown in figure 1 is dedicated to better explain international

performance. The International Competence directly influences the international performance.

We propose this hypothesis (H8) and also the hypothesis (H9) stating that international

competence influences the international experience. These two hypotheses lead to a reflection on

the effect on interactions between the various actors in the organizational environment: it

generates the acquisition of a specialized knowledge to deal with unstable markets, resulting in

gains in competitiveness and playing an important role in creating and transferring knowledge,

and thus favoring international adaptation. Still trying to understand the complex nature of these

relationships, Chandler (1962) identifies the international diversification as a growth strategy that

significantly impacts the strategies of the firm. However, as reported by Léo and Philippe (2008),

this relationship between diversification and performance does not concern all business service

firms. In this study we propose the hypothesis (H10), stating that the international experience

impacts positively international performance, which makes us infer that the international

experience supports a high level of international diversification and impacts the bottom line of

firm.

3 - Data analysis and results

The first result of the empirical testing of our model was to reject the idea that a unique variable

could synthesize service innovation: The ten indicators are not describing a single latent variable

but at least two dimensions should be retained. The first dimension is build from four items and

describes quite well an innovative process in the back office that determines scripts, procedures

and the general business model of the firm. The second dimension clearly points to the fact that

some other innovations are market driven: this dimension associates the search for new clients to

be targeted and the share of sales obtained by newly developed services. It is worth to note that

none of the remaining questions can be associated with these two main dimensions. Moreover,

when we introduce these two dimensions into our research model, its global quality is deeply

deteriorated. This shows that only the main dimension of innovation, the procedure oriented one,

plays a significant role towards international development. This result rejoins the previous

observations that innovation in service activities is mainly oriented towards procedures and

service delivery organization than in the creation of fully new service concepts which remain

quite rare.

The individual reliability was studied for each variable of the model, given by loadings or

correlations between the items and the construct. As proposed by Falk and Miller (1992) we

consider that a variable presents an acceptable convergent validity when the loadings of the

contributing items are greater as 0.55. The items which didn’t comply with this prerequisite were

dropped from the calculations. Table 4 given in Appendix recapitulates the different variables

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009

DEMAND AS A DRIVING FORCE OF SERVICE INNOVATION

23

and the items which could be used in order to measure each of them. Standardized loadings are

given in the same table for each selected item. The 12 following items had to be excluded:

The international performance can not be measured by the six proposed items, two having

to be dropped: ‘international market share’ that some respondents seem to have

understood differently than others and ‘steadiness of international turnover’ which is not

discriminating in our sample where most firms have already developed abroad for long.

The international experience is consistent with only two of the three initial items:

‘experience allows developing anywhere in the world’, has to be suppressed from the

analysis, as it is probably considered exaggerate for all respondents.

The international competence of the staff is correctly estimated by all items but one:

‘Foreign language of market countries’. This reveals that in the managers’ mind, the

international trade knowhow and the mastering of foreign languages are tightly separated.

The R & D organizational capacity loses 3 items from the 5 initially foreseen: two

concerning the personnel’s quality and the other the financial capacity to invest. The first

theme receives often high ratings as it implies an indirect evaluation of the manager’s

efficiency. It is also often hard to obtain sincere answers on financial questions which are

perceived as very sensible by the managers.

The relational capacity was expected to be measured by four items but two have to be

excluded: ‘communication with partners’ and ‘cooperation with possible competitors’.

At last, the ICT use capacity limits to 4 items, 3 being too independent to be associated in

the same variable. These excluded items concern the use for communicating with clients,

for training partners or clients and for payment purposes.

Another result of our first model trials is to reject one of our initial hypotheses (H 8) by which we

assumed that international competence had a direct impact on international performance.

Competence is an asset which has to be put in motion to impact performance. Model variants

including this relationship do not give good results and its deletion enhances all the quality tests.

This means that the data collected privilege two indirect relationships: on the one hand,

International competence impacts international experience which in turn affects international

performance, on the other one, it influences service innovation and has therefore a second

indirect effect on international performance. Thus, the theoretical model presented next examines

the validity of the remaining 9 hypothetical relations.

From a methodological point of view Hair et al. (1998) suggest adopting a two stages analysis for

structural equations modeling. The measurement model should be evaluated before looking at the

theoretical model. The measurement model examines the quality of each latent variable according

to the items that correspond to it. The theoretical model estimates the relationships that are

supposed to exist between the different variables of the model. The logic of this Two Steps

approach is to ensure that the structural relationships will be extracted from a set of measuring

instruments with desirable psychometric properties.

RESER SMALL GRANT 2009