"Who Needs Outside Equity?"

advertisement

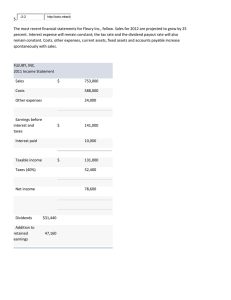

Preliminary Draft – Do Not Cite or Quote Without Permission Who Needs Outside Equity? By Lawrence E. Mitchell The George Washington University I feel like a bit of an interloper here, since I’m not particularly expert in the governance or economics of law firms. But reading through Larry’s and Gordon’s papers, their prior work, and some other work on the subject, what struck me is that one of the major themes underlying the call for law firm deregulation is that it will make capital markets, and particularly equity markets, more accessible to law firms. This struck me as a bit odd. Every student of finance knows that, all else equal, equity is the most expensive form of financing. So why would law firms want to engage in expensive equity financing rather than other possible forms of finance? The scholarly debate involves a lot of theory. I’d like to introduce some facts. A brief look at American finance history suggests that law firms, if they are indeed like other business firms as Larry and Gordon argue, should not be especially interested in equity finance, at least if their goal is to increase their source of productive capital. To illustrate why, I’m going to present some truncated data, which I’ve drawn from a much broader and more detailed study in which I’m engaged, to illustrate the highlights. The punchline is that American business firms don’t typically finance with equity at all. The hypothesis for purposes of this comment is that the only rational purpose for external law firm equity finance is to allow partners to cash out at higher multiples than they can get simply by withdrawing their partnership shares in the ordinary course. A broad historical view demonstrates that external equity financing has been relatively unimportant for US industrial corporations throughout the 20th and 21st centuries (much the same could be said of British companies. I rely on American data because I rely heavily on corporate balance sheet data and I only have had time to examine the IRS archives to see what has been going on. I begin with my research of recent years which has led me to the conclusion that equity financing played a relatively insignificant role in financing American industrialization in the 19th century, whether we’re talking about the first of our major industries, the railroads, or any of the other great enterprises that characterized the American economy for much of the 20th century. Economists writing in the 1950s and early 1960s, when good data first became available, almost universally note the essential irrelevance of the stock market to industrial finance. My own research thus far seems to confirm that from 1926 until the 1960s (based on the best data I have at the moment), retained earnings and debt played a far greater role in capital formation, and thus real economy production, than did equity While limited time requires that I proceed quickly through the slides, the following graphs show the ratios of retained earnings and various forms of debt (long- term, and short-term and accounts payable) to capital. 2005 2002 1999 1996 1993 1990 1987 1984 1981 1978 1975 1972 1969 1966 1963 1959 1956 1953 1950 1947 1944 1941 1938 1935 1932 1929 1926 2005 2002 1999 1996 1993 1990 1987 1984 1981 1978 1975 1972 1969 1966 1963 1959 1956 1953 1950 1947 1944 1941 1938 1935 1932 1929 1926 2005 2002 1999 1996 1993 1990 1987 1984 1981 1978 1975 1972 1969 1966 1963 1959 1956 1953 1950 1947 1944 1941 1938 1935 1932 1929 1926 Surplus and Retained Earnings/Capital 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Accounts payable and short term debt/capital 4.5 5 3.5 4 2.5 3 1.5 2 0.5 1 0 Long Term Debt/Capital 4 3.5 2.5 3 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 As you can see from the graphs, capital, by which I mean outside equity, is a relatively low percentage of financing throughout the historical period. This conclusion is also supported by other data, drawn from the Bureau of Economic Analysis by Simon Kuznets in 1956 and extended to 1962 by Arnold Sametz. These data show that, not only was external equity financing unimportant in general, but that its importance declined significantly in the post-World War II years. RATIOS OF INTERNAL TO TOTAL SOURCES OF FUNDS NON-FINANCIAL CORPORATIONS, 1901-1956 1901-1912 0.55 1913-1922 0.60 1923-1929 0.55 1930-1933 1934-1939 0.98 1940-1949 0.71 1946-1956 0.61 Source: Kuznets, Table 39, page 248. 1957-1962 0. 61 Source: Sametz, Table 4, page 455. Now the data I presented in the graphs have to be qualified. The graphs are drawn from data compiled by Naomi Lamoreaux for the Millenial Edition of the Historical Abstracts of the United States. In compiling IRS data, Lamoreaux presented retained earnings and surplus as an aggregate figure. Of course surplus largely represents capital raised from equity sales, and thus the retained earnings figures are overstated. When I turn to the more recent years, you’ll see that I have separated paid-in surplus and retained earnings from 1978 on, based on the original IRS records. [ I intend to do this going back as far as the IRS records allow, to 1926, but I’m waiting for a response from the IRS to my FOIA request to compel it to let me see the earlier data. ] At any rate, and for what it’s worth at the moment, the graphs support my conclusion, that external equity financing was not terribly important at least through the middle of the century. The question becomes more interesting when the data for the period from 1978 are examined. What becomes immediately apparent is that the historical relative importance of debt and retained earnings as a matter of productive finance diminishes, while the relative importance of stock increases. [To remind you, I compiled these data directly from IRS corporate balance sheet records, so I was able to break out paid-in surplus from retained earnings, thus isolating real external equity.] It turns out that Lamoreaux’s numbers overstate the ratios, but evidently not by much based on the work of Kuznets and Sametz, as well as others. I also combined capital and surplus to give a better idea of funding from external equity in general. Ratio of Ratio of Ratio of Retained Retained Retained Ratio of Retained Ratio of Retained Earnings to Earnings to Long Earnings to Short Accounts Term Debt Term Debt Earnings to Earnings to Capital+Paid External in or Capital Financing Payable Surplus 1978 0.370 1.21 2.070 1.070 2.194 1979 0.366 1.20 1.994 1.084 2.121 1980 0.359 1.13 1.972 1.084 2.118 1981 0.337 0.97 1.887 1.106 1.997 1982 0.305 0.85 1.809 0.987 1.841 1983 0.289 0.77 1.898 0.963 1.678 1984 0.261 0.69 1.764 0.875 1.509 1985 0.230 0.58 1.532 0.804 1.364 1986 0.201 0.47 1.517 0.704 1.272 1987 0.175 0.41 1.344 0.626 1.075 1988 0.166 0.39 1.360 0.591 0.972 1989 0.165 0.37 1.396 0.611 0.951 1990 0.142 0.32 1.289 0.529 0.782 1991 0.132 0.29 0.857 0.534 0.961 1992 0.125 0.26 0.892 0.522 0.918 1993 0.137 0.27 1.134 0.579 1.059 1994 0.126 0.25 1.057 0.548 0.928 1995 0.148 0.29 1.253 0.657 1.078 1996 0.152 0.29 1.322 0.690 1.082 1997 0.164 0.31 1.475 0.765 1.206 1998 0.151 0.28 1.350 0.701 1.050 1999 0.154 0.29 1.416 0.726 1.080 2000 0.120 0.22 0.965 0.587 0.902 2001 0.065 0.12 0.543 0.314 0.516 2002 0.032 0.06 0.273 0.155 0.291 2003 0.068 0.13 0.532 0.313 0.577 2004 0.089 0.18 0.581 0.402 0.745 2005 0.111 0.21 0.718 0.520 1.033 Source: IRS Look especially at column 1, the ratio of retained earnings to external financing. In place of the Kuznets-Sametz first half century range of 55% to 71% (leaving aside the extraordinary 98% during the period when America was emerging from the Great Depression), we see 37% in 1978, dropping as low as 3% in 2002 (which can be explained by the consequences of 9/11), but still well below 20% from 1986 on. Clearly, the importance of retained earnings in relation to external financing has evaporated and, as you can see from the chart, this is also true of the various forms of debt, although accounts payable shows some degree of relative stability. The next graph maps all of the ratios together: Ratio of Retained Earnings and Other Debt to Total External Financing 0.400 0.350 0.300 0.250 0.200 0.150 0.100 Ratio of Retained Earnings to External Financing Ratio of Accounts Payable to External Financing Ratio of LT Debt toExternal Financing 0.050 Ratio of ST Debt to External Financing Ratio of Capital+Paid in or Capital Surplus to External Financing 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996 1994 1992 1990 1988 1986 1984 1982 1980 1978 0.000 Perhaps the most striking thing about these data is not only that they depart from historical trends but that they are entirely counterintuitive. For what we see is that, almost precisely when the going-private movement began, in the late ‘70s, in the form of leveraged transactions, in which it has principally continued, the relative importance of retained earnings and all forms of debt plummet and equity rises. In light of the fact that, by definition, going private transactions remove equity from the public market, and the common understanding that debt financing was the principal means of accomplishing this, we would expect to see exactly the opposite result, even accounting for the dot.com boom of the late ‘90s. The diminution in the ratio of retained earnings to external financing by itself isn’t especially surprising, since one characteristic of attractive takeover targets is large amounts of cash with which to pay debt service, and one might conclude that leveraged going private transactions eat internal equity and continue to eat cash flows that might add to that equity, but the debt numbers in light of what we know, or at least think we know, about the period are astonishing, although some portion of this diminution undoubtedly is accounted for by off-balance sheet financing transactions. The astonishment is compounded when we also recognize that the mid-‘90s to the present have been a time of historically low interest rates, which would also suggest that debt financing would have become increasingly attractive as a matter of financing productivity. And add to the going private transactions data showing huge volumes of corporate stock buybacks, also suggestive of a diminution in outstanding equity, and the reverse trends become even more puzzling. S&P 500 - Stock Buybacks (Billions of Dollars) 200 180 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 Mar-98 Jun-98 Sep-98 Dec-98 Mar-99 Jun-99 Sep-99 Dec-99 Mar-00 Jun-00 Sep-00 Dec-00 Mar-01 Jun-01 Sep-01 Dec-01 Mar-02 Jun-02 Sep-02 Dec-02 Mar-03 Jun-03 Sep-03 Dec-03 Mar-04 Jun-04 Sep-04 Dec-04 Mar-05 Jun-05 Sep-05 Dec-05 Mar-06 Jun-06 Sep-06 Dec-06 Mar-07 Jun-07 Sep-07 0 Market Value Operating Earnings AS Reported Earnings Dividends Buybacks Mar-98 8,626 86 81 29 26 Jun-98 8,956 90 78 33 29 Sep-98 8,125 83 72 34 38 Dec-98 9,942 93 69 32 32 Mar-99 Jun-99 10,513 11,232 96 108 90 102 33 34 34 32 Mar03 Jun03 Sep03 Dec03 Mar04 Jun- Market Value Operating Earnings AS Reported Earnings Dividends Buybacks 7,827 115 110 36 30 9,001 119 103 38 28 9,208 133 126 40 34 10,286 138 122 47 39 10,461 10,623 147 158 141 142 42 43 43 42 Sep-99 10,554 107 98 37 31 Dec-99 12,315 115 107 34 45 Mar-00 12,686 118 116 35 49 Jun-00 12,484 128 116 35 37 Sep-00 12,599 124 120 36 31 Dec-00 11,715 116 80 35 34 Mar-01 10,463 91 50 36 33 Jun-01 10,385 96 82 34 31 Sep-01 11,027 81 44 35 34 Dec-01 9,437 83 47 38 35 Mar-02 10,502 99 84 35 30 Jun-02 9,091 107 63 38 31 04 Sep04 Dec04 Mar05 Jun05 Sep05 Dec05 Mar06 Jun06 Sep06 Dec06 Mar07 Jun07 10,398 157 132 46 46 11,289 167 130 50 66 10,820 164 154 49 81 10,890 178 167 49 81 11,083 170 161 55 104 11,255 182 156 53 100 11,660 187 177 54 117 11,497 199 182 55 110 12,020 207 193 62 105 12,729 197 182 58 118 12,706 200 191 58 118 13,350 205 208 59 158 In the three year period ended December 31, 2007, the corporations comprising the S&P 500 spent $1.3 trillion in buybacks, compared to $1.27 trillion on capital expenditures, $376 billion on R&D, and $605 billion on dividends. And while aggregate data can be misleading, 279 of the S&P 500 companies spent more on buybacks than capital investment. [During this period, 12.5% of the outstanding shares on the market were removed due to buybacks alone, just under a majority of which went into treasury stock with the balance used for M&A and options.[ Financial corporations, while active in buybacks, only account for 20% of the buybacks in recent years. The relevance of this last fact will become clear in a moment. The reverse trend becomes positively astounding when you look at Federal Flow of Funds data and see that from 1982, except for two brief periods between 1991 and 1993, and between 2000 and 2003, net equity issuances by all corporations have been flat or negative, and that a significant dip occurs between 1996 and 1998 during the dot.com boom: Corporate Equity - Net issues (Billions of Dollars) 200 100 0 -100 -200 -300 -400 2006 2003 2000 1997 1994 1991 1988 1985 1982 1979 1976 1973 1970 1967 1964 1961 1958 1955 1952 1949 1946 -500 It then occurred to me to separate out non-financial corporations from financial corporations and here’s what we get. An immaterial positive blip here and there but tending around zero to deeply negative in the case of non-financial corporations, largely following the overall story for all corporations: Corporate Equity - Nonfinancial Corporate Business (Billions of Dollars) 100 0 -100 -200 -300 -400 -500 -600 So perhaps the dramatic increase appears elsewhere, and the likely suspect is on the balance sheets of financial corporations. In fact it does. Note that the first uptrend begins almost precisely at the time of the beginning of the going-private movement, when overall equity issuances were down, and 2006 2003 2000 1997 1994 1991 1988 1985 1982 1979 1976 1973 1970 1967 1964 1961 1958 1955 1952 1949 1946 -700 that the most recent and significant up-trend begins in 1997, just a year after the big dip started during the dot.com boom when we thought we saw countless IPOs: Corporate Equity - Financial Sectors (Billions of Dollars) 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 -20 So here we are. Financial corporations, which have huge demands for liquid capital, are the only class of American corporations that issue significant amounts of equity for financing purposes. The entire history of American finance in the 20th and 21st centuries tell us that no other class of corporation issues large amounts of equity to finance the formation of productive capital. While I don’t have final data yet, it appears that much of the equity issued during the late 1990s was secondary, to provide liquidity for entrepreneurs and venture capitalists, not for corporate production. So I end with the question with which I began. Why would law firms issue equity? It cannot be the case 2006 2003 2000 1997 1994 1991 1988 1985 1982 1979 1976 1973 1970 1967 1964 1961 1958 1955 1952 1949 1946 -40 that they have anything like the need for liquid capital that financial firms do. The obvious conclusion is that it is the liquidity of the partners, not the firms, that matters. If this is true, and unless law firms are dramatically different from other kinds of industries, which in this respect I doubt, the deregulation of law firms to allow them to access capital markets requires serious examination with this conclusion in mind. I don’t remotely have time to go into how the analysis changes, or the implications of allowing law firms to access the public markets, but clearly it does.