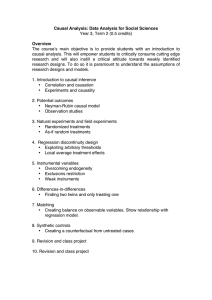

The Importance of Experimental Evidence for Social Science Research

advertisement

The Importance of Experimental Evidence for Social Science Research Why causal answers are needed and how we can get them Dr Steven Stillman Senior Fellow, Motu Adjunct Professor of Economics, Waikato NIDEA Theme Leader, New Zealand’s individuals, families and households Launch Symposium, November 24th 2010 Why are causal answers needed? • Policymakers need to know the relative effectiveness of particular policy changes or interventions. – Using standard statistical methods, it is straightforward to examine whether there is an association between, for example, an education policy reform and student outcomes. – However, in this case, distinguishing causation from association requires strong assumptions about the underlying model of student achievement and the optimising behaviour of students, parents, teachers, and schools depending on the policy. – Without the ability to observe what would have happened to students both if the reform had and had not occurred, it is not possible to estimate the causal impact of the policy change without relying on untestable assumptions. Why are causal answers needed? • Perceived wisdom is not always correct – The Moving to Opportunity program randomly gave housing vouchers to families living in high poverty public housing projects in five US cities that encouraged them to move to wealthier neighbourhoods. This had no impact on adult economic self-sufficiency or labour market outcomes, although mental health did improve (Kling et al. 2007). – Edin et al. (2003) found that, while refugees who settled in ethnic enclaves in Sweden had worse labour market outcomes, once sorting was controlled for using a policy experiment which randomly placed individuals, living in an enclave improved labour market outcomes for less skilled immigrants. – Stillman et al. (2009) found that migration improved the mental health of Tongan migrants to New Zealand who came via randomly allocated places in the Pacific Access Category, especially for migrants in poor mental health. Why are causal answers needed? • Selection is complicated – The Pacific Island – New Zealand Migrant Survey (PINZMS) collected information on Tongan migrants to New Zealand who came via randomly allocated places in the Pacific Access Category, unsuccessful applicants to this ballot and Tongans who have not applied to the migration ballot – Comparing the characteristics of unsuccessful applicants and non-applicants allows us to examine migrant self-selection – Consistent with migration theory, we find that ‘migrants’ are more educated and also have higher income relative to their education – However, ‘migrants’ have lower mental health, which may explain why migration is often claimed to cause mental health problems – No evidence is found of a ‘healthy’ immigrant effect when looking at physical health. Hence, any differences in physical health between migrants and non-migrants reflect the causal impact of migration on health. How can we get causal answers? • This is where experimental design comes in. – Continuing with my initial example, by randomly assigning students, teachers or schools to two groups, one which is impacted by the reform and one which continues life under the status quo, it is now possible to estimate the impact of the reform on student outcomes without any assumptions about the underlying behavioural models. – Randomisation ensures that any observed differences in outcomes cannot be caused by other differences between the students, teachers and schools being impact by the reform and those not being impacted by the reform Other advantages of social experiments • Well designed experiments can gain new insights – Kremer and Chen (2001) ran an experiment in Kenya to discourage teacher absences. Each pre-school headmaster was entrusted with monitoring the presence of the teacher and a prize was to be given to teachers with a good attendance record. The experiment seemed to indicate that having this incentive discouraged absences, but when the research team independently verified absence through unannounced visits, they found the entire effect was due to the headmasters cheating. – Giné et al. (2009) designed and tested a voluntary commitment product to help smokers quit smoking. The product offered smokers a savings account in which they deposited funds for six months, after which they took a urine test. If they passed, their money was returned; otherwise, their money was forfeited to charity. Eleven percent of smokers in the sample took up the offer which could lead to forfeiting 20% of monthly income. Smoking rate declined by 31-53 percentage points for this group and still persisted in surprise tests 12 months later (see http://www.stickk.com/) Other advantages of social experiments • Well designed experiments can test important theories – Ashraf et al. (2006) designed a commitment savings product for a bank in the Philippines. Individuals could restrict access to the funds they deposited until a given amount was achieved. This was randomly assigned and used to test whether clients had time-inconsistency in preferences. – Karlan and Zinman (2005) tested the relative importance of repayment burden versus adverse selection in causing default among high-risk borrowers. They did this by first randomly offering potential borrowers with the same observable risk a high or a low interest rate and then randomly giving a new lower offer to some who agreed to borrow at the high rate. – Bertrand et al. (2005) use the same setup to test a broader set of hypotheses, most of them coming directly from psychology. Now, the offer letters were made to vary along other dimensions that should not matter economically. For example, the lender varied the description of the offer, compared the offered interest rate to a “market” benchmark, added in a promotional giveaway, and manipulated the race and gender features of the lender introduced via the inclusion of a photo in the corner of the letter. Thank you stillman@motu.org.nz www.waikato.ac.nz/nidea www.pacificmigration.ac.nz