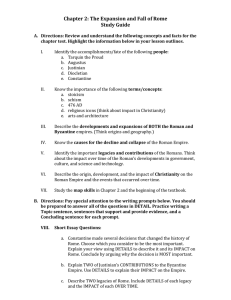

2.2- Rome and the Spread of Christianity

advertisement

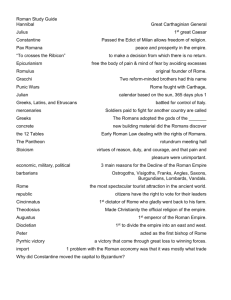

2.2 Rome & the Rise of Christianity The Emergence of Rome The Emergence of Rome Indo-European peoples moved into Italy from about 1500 to 1000 B.C. One people spoke Latin, an Indo-European language, and lived as herders and farmers on Italy’s hills After 800 B.C., other people, including the Greeks and Etruscans, settled in Italy Early Rome was ruled by kings, some of whom were Etruscan The Emergence of Rome In 509 B.C., the Romans overthrew the last Etruscan king and established a republic In a republic the leader is not a king and certain citizens have the right to vote Enemies surrounded Rome, and so the young republic began a long period of continuous warfare By 264 B.C., Rome had defeated the Greeks and remaining Etruscan states and controlled almost all of Italy The Emergence of Rome To rule, the Romans devised the Roman Confederation Some people had full Roman citizenship Other groups were allies who controlled their local affairs but gave soldiers to Rome Such people could become Roman citizens Thus many of the conquered peoples felt invested in Rome’s success The Emergence of Rome Rome faced a strong power in the Mediterranean–Carthage, which was founded around 800 B.C. on the coast of North Africa Carthage had a large trading empire in the western Mediterranean The Romans fought three wars with Carthage- The Punic Wars During the Second Punic War, the victories of Carthage’s greatest general, Hannibal, almost brought Rome to disaster After creating new armies and a navy, the Romans defeated Hannibal’s forces Spain became a Roman province, and Rome controlled the western Mediterranean Rome completely destroyed Carthage in 146 B.C. The Emergence of Rome In the second century B.C., Rome also conquered Macedonia and Greece. In 129 B.C., Pergamum became Rome’s first province in Asia Rome was now master of the Mediterranean Sea The Roman State The Romans distrusted kingship because of their experience with Etruscan kings Patricians were members of the small amount of wealthy Roman families. Early Rome was divided into two groups, the patricians and the plebeians Plebeians were the majority of the population (workers, shopkeepers, and peasants). They built a different form of government Patricians were large landowners who formed Rome’s ruling class The plebeians were the less-wealthy landholders, craftspeople, merchants, and small farmers Members of both groups were citizens and could vote Only patricians could be elected to public office The Roman State The chief executive officers of the Roman Republic were the consuls and praetors. Two consuls ran the government and led the army into battle The praetor directed the civil law–law as it applied to citizens Later another praetor was added to handle the law as it applied to non-citizens The Roman Senate was especially important About three hundred patricians who served for life made up the original Senate At first only an advisory body, by the third century B.C. the Senate had the force of law The Roman State The most important people’s assembly was the centuriate assembly It elected the consuls and praetors, and passed laws It was organized by classes based on wealth, so the wealthiest citizens always were the majority There was often conflict between the patricians and the plebeians The plebeians wanted political and social equality Finally, in 471 B.C., a popular assembly called the council of the plebs was created New officials, called the tribunes of the plebs, were empowered to protect the plebeians The Roman State By 287 B.C., all male Roman citizens were supposedly equal under the law However, a few wealthy patrician and plebeian families formed a new senatorial ruling class that came to dominate political office the Roman Republic had not become a democracy From Republic to Empire Between 509 and 264 B.C., Rome expanded to control most of what is present-day Italy By 129 B.C., Rome controlled the Mediterranean Sea Rome’s republican institutions could not rule an empire The Senate became the real governing body Rival factions within the Senate fought for power and created disorder In the first century B.C., Roman leaders began to recruit armies that swore allegiance to the general and not to the state From Republic to Empire Between 82 and 31 B.C., various individuals including Julius Caesar competed for power After Caesar’s assassination, his grandnephew Octavian took control of the Roman world The period from 31 B.C. to A.D. 14 is known as the Age of Augustus In 27 B.C., the Senate awarded Octavian the title of Augustus (“the revered one”) Augustus controlled the army and thus had great power The Senate gave Augustus the title imperator (commander in chief) from which our word emperor is derived Augustus became the first emperor of the Roman Empire. The Early Empire The period called the Early Empire lasted from A.D. 14 to 180 During part of this time (A.D. 96–180), a series of five so-called good emperors–Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius–led Rome and created a time of peace and prosperity called the Pax Romana (“Roman Peace”) The good emperors respected the ruling classes, ended arbitrary executions, maintained peace, and supported domestic policies that benefited the empire These emperors, however, also took power away from the Senate Officials appointed and directed by the emperor began to run the government The Early Empire The good emperors instituted programs to help the people Trajan provided funds to help the poor educate their children Trajan and Hadrian were especially active in building public works–aqueducts, bridges, roads, and harbor facilities By the second century, the Roman Empire covered about three and a half million square miles and had a population estimated at over 50 million The Early Empire The Early Empire was prosperous Internal peace helped trade grow Merchants from across the empire came to the main Italian ports Trade went beyond the empire’s frontiers and included silk goods from China Large amounts of grain were imported to feed the people, and luxury items came in for the rich Farming, however, remained the chief occupation and the basis of Roman prosperity Roman Law One of Rome’s most important contributions to society was its system of law Rome’s first code of law, the Twelve Tables, was adopted in 450 B.C. Later Rome adopted a more sophisticated system of civil law, which applied to Roman citizens only As Rome expanded and special rules were needed, a body of law was developed known as the Law of Nations, which the Romans considered as natural law, or universal law based on reason These standards included principles still recognized today: a person was innocent until proven guilty people accused of wrongdoing were allowed to defend themselves judges weighed evidence carefully before arriving at a decision. Slavery in the Roman Empire No people relied on slavery as much as the Romans As Rome conquered the Mediterranean area, large numbers of war captives were brought to Italy as slaves Greeks were prized as tutors, musicians, doctors, and artists Slaves worked in shops, made crafts, and performed household tasks such as cleaning and gardening Slaves also built roads and public buildings, and farmed large estates of the wealthy Conditions for slaves were often pitiful One Roman writer argued that it was cheaper to work slaves to death and replace them than to care for them Slavery in the Roman Empire Some slaves revolted The most famous slave revolt in Italy was led by the gladiator Spartacus in 73 B.C. Seventy thousand slaves joined Spartacus and defeated several Roman armies before being defeated in 71 B.C. Spartacus was killed, and thousands of his followers were crucified Daily Life in the City of Rome Rome had the largest population of any city in the empire, close to one million by the time of Augustus Rome was overcrowded and noisy Wagons and carts were banned from the streets during the day to ease the congestion There was a great gulf between rich and poor While the rich lived in comfortable villas, the poor lived in apartment blocks called insulae As tall as six stories, these poorly constructed buildings often collapsed Fires were a constant threat Daily Life in the City of Rome High rents forced entire families to live in one room The apartments did not have any plumbing or central heating These uncomfortable conditions caused many Romans to spend most of their time outdoors in the street Rome had unequaled public buildings–such as baths, temples, theaters, and markets–but poverty remained a problem Beginning with Augustus, the city’s two hundred thousand poor received free grain from the emperor Daily Life in the City of Rome Grand public spectacles entertained the people Emperors often mounted these spectacles as part of religious festivals The festivals featured horse and chariot races at the Circus Maximus, dramatic performances in theaters, and very popular gladiatorial shows Roman Culture Latin literature’s high point was during the Age of Augustus. The most distinguished poet of the Augustan Age was Virgil, who wrote his epic poem the Aeneid in honor of Rome The character Aeneas displays the virtues of the ideal Roman–duty, piety, and loyalty By establishing the Romans in Italy, Aeneas started the city on its divine mission to rule the world In the third and second centuries B.C., the Romans developed a taste for Greek art Greek statues adorned their cities and homes Reproductions became popular Roman sculptors added realistic, even unpleasant, features to the idealized Greek forms Roman Culture The practical-minded Romans excelled in architecture The Romans continued to use Greek styles (colonnades and rectangular buildings) and created forms based on curved lines: the dome, arch, and vault They were the first people to use concrete on a massive scale The Romans were first-class engineers who built enduring roads, bridges, and aqueducts. They built 50,000 miles of roads throughout the empire Rome’s many aqueducts supplied one million people with water The Emergence of Christianity By A.D. 6, Judaea, which covered the lands of the ancient kingdom of Judah, was a Roman province under the direction of a procurator Unrest was common in Judaea, even among factions of Jews A Jewish revolt began in A.D. 66 but was crushed by the Romans four years later The Emergence of Christianity A few decades before the revolt, a Jewish prophet named Jesus began to preach throughout Judaea Jesus taught that inner transformation was more important than adhering to laws or rituals Individuals should treat others as they would like to be treated People should love God and love each other, treating all as neighbors Jesus taught the virtues that would later shape the value system of Western civilization: humility, charity, and love of others The Emergence of Christianity Jesus’ opponents turned Jesus over to the Roman authorities because they feared he might cause people to revolt against Rome The procurator, Pontius Pilate, ordered Jesus crucified Followers of Jesus, however, believed he overcame death Many Jewish followers believed that Jesus was the Messiah, the long-expected savior of Israel The Spread of Christianity Simon Peter was a prominent leader in early Christianity Peter and the other apostles taught that Jesus was the Savior and Son of God come to Earth to save all people Jesus’ death had made up for people’s sins and made salvation possible Individuals had only to accept Christ as their Savior to be saved Another prominent leader was Paul, who followed Jesus’ command to preach the gospel to both Jews and nonJews, or Gentiles He founded many Christian communities in Asia Minor and along the Aegean Sea The Spread of Christianity Christian teachings were passed down orally, and some were preserved in writing by Jesus’ disciples and followers Between A.D. 70 and 100, these writings became the basis of the written Gospels (“the good news”) The Gospels tell of Jesus’ life and teachings, and they form the basis of the New Testament, the second part of the Christian Bible By 100, Christian churches had been established throughout the eastern empire and parts of the western empire The Triumph of Christianity Romans came to see Christianity as harmful to the public order because Christians would not worship the Roman gods, an act of treason Christians believed in one God only and would not worship false gods or the emperors for fear of endangering their salvation Roman persecution of Christians began under Nero (A.D. 54–68), who blamed them for the fire that destroyed much of Rome He subjected them to cruel deaths The Triumph of Christianity Roman persecution strengthened Christianity by forcing it to become more organized The emerging control of bishops over Christian communities was an important part of this change The Christian Church created a new structure in which the clergy (church leaders) were distinct from the laity (everyday church members) Christianity attracted many followers First, it was more personal than the Roman religion and offered eternal life and salvation Second, it gave people a sense of belonging to a community Third, Christianity appealed to every class and was especially attractive to the poor and powerless Every individual, regardless of status, could gain salvation The Triumph of Christianity Christianity prospered in the fourth century Constantine became the first Christian emperor In 313, his Edict of Milan proclaimed official toleration of Christianity Under Theodosius the Great, the Romans adopted Christianity as their official religion The Decline A long period of civil wars, political disorder, and economic decline followed the death of the last good emperor, Marcus Aurelius, in A.D. 180 At the end of the third and the beginning of the fourth centuries, the emperors Diocletian and Constantine revived Rome, founding a state called the Late Roman Empire This state had a new governmental structure, a rigid economic and social system, and a new religion–Christianity. Diocletian ruled from 284 to 305 Believing the empire was too large for only one ruler, he divided the empire into four sections, each with its own ruler Diocletian’s military power gave him ultimate authority over the other three rulers Constantine, who ruled from 306 to 337, extended many of Diocletian’s policies The Decline Both emperors expanded the bureaucracy and enlarged the army to five hundred thousand troops. Their expansion of the civil service and the military drained the treasury More money was needed, but a lack of population growth meant that the tax base could not be increased To preserve the existing tax base, the emperors issued edicts forcing people to stay in their assigned jobs The Decline By 324, Constantine was the sole ruler of the Roman Empire His biggest project was building a new capital city in the east on the site of Byzantium on the shores of the Bosporus Constantine filled his “New Rome” with a forum, large palaces, and an amphitheater Constantinople would become the center of the Eastern Roman Empire and one of the world’s greatest cities. The policies of Diocletian and Constantine were based on control and coercion In the long run, they stifled the vitality that the empire needed to survive The Fall The empire restored by Diocletian and Constantine continued for another hundred-plus years It was divided into two parts and had two capitals, Rome in the west and Constantinople in the east In the second half of the fourth century, Huns from Asia moved into eastern Europe and put pressure on the German Visigoths The Visigoths moved south, crossing the Danube River into Roman territory Initially Roman allies, the Visigoths revolted and defeated a Roman army in 378 The Fall More Germans crossed into Roman lands. In 410 the Visigoths sacked the city of Rome In 455 another group called the Vandals also sacked the city Our modern word vandal comes from the name of this ruthless tribe In 476 the western emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed by the Germanic head of the army This event is usually used to mark the end of the Western Roman Empire The Eastern Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, however, continued to thrive