Defining Principles-Based Accounting Standards By Rebecca Toppe Shortridge and Mark Myring

advertisement

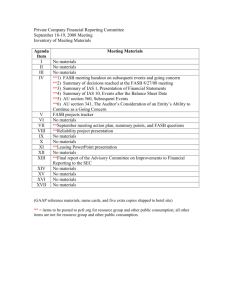

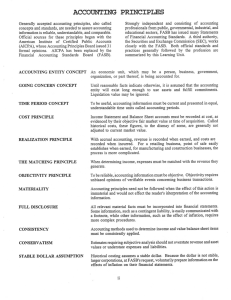

Defining Principles-Based Accounting Standards By Rebecca Toppe Shortridge and Mark Myring E-mail Story Print Story A key concern arising from the recent business scandals is that U.S. accounting standards have become “rules-based,” filled with specific details in an attempt to address as many potential contingencies as possible. This has made standards longer and more complex, and has led to arbitrary criteria for accounting treatments that allow companies to structure transactions to circumvent unfavorable reporting. In addition, the quest for bright-line accounting rules has shifted the goal of professional judgment from consideration of the best accounting treatment to concern for parsing the letter of the rule. To address these concerns, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 required the SEC to examine the feasibility of a principles-based accounting system. The SEC rendered an interesting study that focuses on “objective-oriented” standards (www.sec.gov/news/studies.shtml). Accounting firm leaders have supported a move toward principles-based standards. Sam DiPiazza, CEO of PricewaterhouseCoopers, and Ed Nusbaum, CEO of Grant Thornton, have both publicly proposed a switch to principles-based standards. The Financial Accounting Standards Committee (FASC) of the American Accounting Association believes that a principles-based approach is more likely to result in transactions that reflect their true economic substance. Finally, FASB Chair Robert Herz has said that the current rules-based system is problematic because “those who want to comply with rules ... are not always sure of everything they need to look at. Those looking to get around the rule … can use legalistic approaches to try and do it” (Business Week online, 2002). Despite all of this discussion, a precise definition of principles-based accounting remains elusive. What follows is a proposed definition and an explanation of how standards developed according to this definition would differ from the current system. The usefulness of the definition is demonstrated by a comparison of U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and International Accounting Standards (IAS) regarding the treatment of leases. Principles-based accounting has advantages and disadvantages, which should be weighed in the context of FASB-proposed movement toward principlesbased accounting. Principles-Based versus Rules-Based Accounting Simply stated, principles-based accounting provides a conceptual basis for accountants to follow instead of a list of detailed rules. In a 2002 presentation to the Financial Executives International, Robert Herz, Chairman of FASB, explained it as follows: Under a principles-based approach, one starts with laying out the key objectives of good reporting in the subject area and then provides guidance explaining the objective and relating it to some common examples. While rules are sometimes unavoidable, the intent is not to try to provide specific guidance or rules for every possible situation. Rather, if in doubt, the reader is directed back to the principles. GAAP is a principles-based system—at least when standards are initially contemplated. Essentially, the Statements of Financial Accounting Concepts provide a roadmap to establishing standards. The problem arises when specific standards come up for consideration. FASB member Katherine Schipper has explained that one of the overriding financial accounting concepts is the usefulness of accounting information to decision makers. This implies that the information should be relevant, reliable, and comparable across reporting periods and entities. If the only requirements were that information be relevant and reliable, entities would adopt reporting methods to best reflect the economic realities for their particular entity. But this would make comparison between companies and across reporting periods virtually impossible for investors. The problem arises when standards setters approach the difficult task of determining the appropriate level of detailed guidance to achieve sufficient comparability and consistency in financial statements. A principles-based standard often becomes a rules-based standard in an effort to increase comparability and consistency. An example of this process is demonstrated by SFAS 133, Accounting for Derivative and Hedging Activities, which requires that all financial instruments be measured at fair value. A fundamental question addressed in this standard is the definition of a derivative. SFAS 133 provides three paragraphs to define a derivative. FASB received so many questions about the definition that the Derivatives Implementation Group has issued at least 22 statements to provide additional clarification. A further question is how to measure the fair value of an identified derivative. If no guidance is provided on this issue, numerous measures of fair value are potentially justifiable: the asking price, the bid price, or the average of the bid and ask prices. Thus, a rule was added to delineate exactly how fair value should be determined. Thus, a principle requiring financial instruments to be measured at fair value became a detailed rule with complex stipulations and exceptions that allow corporations to structure contracts to achieve favorable reporting. Lease Accounting Under Rules-Based and Principles-Based Approaches The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) has primarily followed a principles-based approach to standards setting. Thus, their standards provide a comparison to FASB’s approach. Principles-based accounting for leases is addressed in six IASB pronouncements and one interpretation. In contrast, U.S. GAAP related to lease accounting is addressed in 20 Statements, nine FASB Interpretations, 10 Technical Bulletins, and 39 EITF Abstracts. The depth of GAAP coverage of leases is characteristic of the rules-based accounting system in the U.S. Accounting for leases is primarily addressed in International Accounting Standard 17 (IAS 17). This standard provides broad guidance on classifying lease contracts as capital or operating. (The Exhibit shows the criteria used to differentiate between capital and operating leases.) The principles-based IAS 17 states simply that a lease “is classified as a finance (i.e., capital) lease if it transfers substantially all of the risks and rewards incident to ownership” to the lessee. IAS 17 does not provide an opportunity to write contracts that avoid minimum requirements. If the substance of the lease is capital, the property must be recorded as an asset and liability on the lessee’s books. In essence, under IAS 17 it is difficult for companies to write lease contracts that allow off–balancesheet financing. SFAS 13, the primary standard for lease accounting in U.S. GAAP, is an example of a rules-based standard. SFAS 13 was enacted in an attempt to force corporations to recognize the substance over the form of a leasing agreement. Specifically, during the 1980s, many companies began using leasing arrangements as a means of off–balancesheet financing. In some instances, companies would buy a piece of equipment, sell it to another entity, and then lease it back to avoid recording an asset and a liability for the equipment. SFAS 13 requires that firms distinguish between operating and capital leases using four specific criteria, whose purpose is to ensure that leases that are essentially purchases be treated as such (see the Exhibit). If a contract satisfies any of the four criteria, it must be recognized as a capital lease in the financial statements. FASB hoped that by providing explicit rules, individual judgment would be eliminated and the standards would be consistently applied. In many respects, this strategy backfired. Because precise rules were established, companies carefully structured lease contracts to qualify as operating leases. As a result, the explicit rule allows the off–balance-sheet financing to continue, and provides justification for the treatment. Advantages and Disadvantages of Principles-Based Accounting What are the advantages and disadvantages of principles-based accounting? Perhaps the primary benefit of principles-based accounting rests in its broad guidelines that can be applied to numerous situations. Broad principles avoid the pitfalls associated with precise requirements that allow contracts to be written specifically to manipulate their intent. A 1981 study sponsored by FASB found evidence that managers purposefully try to structure leases as operating leases to avoid incurring additional liabilities. Providing broad guidelines may improve the representational faithfulness of financial statements. In addition, principles-based accounting standards allow accountants to apply professional judgment in assessing the substance of a transaction. This approach is substantially different from the underlying “box-ticking” approach common in rulesbased accounting standards. FASB Chair Robert Herz has stated that he believes the professionalism of financial statements would be enhanced if accountants are required to utilize their judgment instead of relying on detailed rules. Another advantage of a principles-based system is that it would result in simpler standards. Herz has claimed that a principles-based system would lead to standards that would be less than 12 pages long, instead of over 100 pages (BusinessWeek online, 2002). Principles would be easier to comprehend and apply to a broad range of transactions. Harvey Pitt, former SEC chairman, explained this as follows: “Because standards are developed based on rules ... they are insufficiently flexible to accommodate future developments in the marketplace. This has resulted in accounting for unanticipated transactions that is less transparent.” Finally, the use of principles-based accounting standards may provide accounting statements that more accurately reflect a company’s actual performance because, as Australian Securities and Investments Commission Chair David Knott has stated, an increase in principles-based accounting standards would reduce manipulations of the rules (Nationwide News, 2002). Conversely, there are potential drawbacks to a principles-based approach to standards setting. A lack of precise guidelines could create inconsistencies in the application of standards across organizations. For example, companies are required to recognize both an expense and a liability for a contingent liability that is probable and estimable. On the other hand, a contingent liability that is reasonably possible is only reported in the footnotes. With no precise guidelines, how should companies determine if liabilities are probable or only reasonably possible? The lack of bright-light standards may reduce comparability and consistency, a primary precept of financial accounting. Many accountants seem to prefer rules-based standards, possibly because of their concerns about the potential of litigation over their exercise of judgment in the absence of bright-line rules. The number of requests for implementation guidance received by FASB has always been high, and their significance resulted in the formation of the Emerging Issues Task Force. If financial statements conform with accepted rules, the bases for a lawsuit are diminished. Future of Principles-Based Accounting In October 2002, FASB issued a proposal concerning a principles-based approach to standards setting. The proposal discusses the objectives of financial accounting and how a principles-based approach would help to accomplish those objectives. It also provides an outline for the conversion to a principles-based approach, which entails three priorities. First, the current conceptual framework, which provides guidance for standards, has been characterized by FASB as “incomplete, internally inconsistent, and ambiguous.” For example, while FASB’s Concept Statement 2 discusses the qualities of relevance and reliability, it does not provide any guidance for trading one for the other. In addition, the revenue recognition principles contained in Concept Statement 5 are frequently inconsistent with the definitions of assets and liabilities in Concept Statement 6 (FASB 2002). Because of the current shortcomings of the conceptual framework, the first step in establishing a principles-based system is to improve the accounting concepts and develop an overall reporting framework. Second, the number of exceptions contained in the standards must be reduced. Much of the current detail in standards arises from three kinds of exceptions: scope, transition, and application. Scope exceptions allow the use of prior standards to continue when a new standard is adopted. Transition exceptions reduce the effects of changing to a new standard. Application exceptions are granted to obtain a desired accounting result. For example, to reduce the volatility of pension expenses, estimated returns on plan assets are utilized instead of actual returns. While scope and transition exceptions would still occur, FASB has proposed eliminating application exceptions in a principles-based system. The reduction in exceptions would greatly reduce the details and complexity of standards and more clearly reflect the economic events of an entity. Finally, much of the interpretive and implementation guidance to standards would be eliminated in the move to a principles-based approach. This change poses difficulties; FASB has received an increasing number of requests for implementation guidance from its constituents. The intention of interpretive and implementation guidance is to increase comparability between reporting entities. However, in recent years the amount of guidance has increased substantially. Thus, FASB must decide what guidance is appropriate and how much guidance is too much. In a 2002 interview with Business Week, Herz indicated that a change to principles-based standards would be gradual. Instead of starting all over, any new standards would follow the principles-based method but existing standards would not currently be replaced. FASB’s goal would be a smooth transition rather than an abrupt switch in accounting standards. Implementation of a principles-based approach to standards setting will not be easy, however. It will require a fundamental shift in attitude from all constituents of financial accounting information, including standards setters, the SEC, investors, preparers, auditors, and the public. Rebecca Toppe Shortridge, PhD, CPA, and Mark Myring, PhD, are both assistant professors in the department of accounting at the Miller College of Business, Ball State University, Muncie, Ind