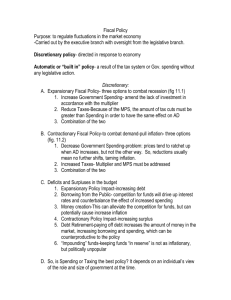

Fiscal Policy: Taxes, Spending, and the Federal Budget

advertisement

Fiscal Policy: Taxes, Spending, and the Federal Budget Slides by: John & Pamela Hall ECONOMICS: Principles and Applications 3e HALL & LIEBERMAN © 2005 Thomson Business and Professional Publishing Fiscal Policy: Taxes, Spending, and The Federal Budget • Almost every year throughout 1980s, and early 1990s, a best-selling book would be published that predicted economic disaster for United States and world • During late 1990s, as federal budget picture improved, these disaster books quietly disappeared • Then, in 2002, another flip-flop – Government was again running a deficit, and more deficits were projected till the end of the 2000s and beyond • What caused these flip-flops in the government’s budget? – And why should we care? 2 Thinking About Spending, Taxes, and the Budget • In 1959, federal government’s total outlays were $92 billion – Goods and services, transfer payments, and interest on its debt • By 2003 total had grown to $2,140 billion, an increase of more than 2,200% • Consider national debt—total amount government owes to the public from past borrowing in years in which it ran a budget deficit – In 1959, national debt was $209 billion • By beginning of 2003, it had grown to $2,936 billion – Is this our evidence that debt is crushing economy? 3 Thinking About Spending, Taxes, and the Budget • From 1959 to 2003 U.S. population grew, labor force grew, and average worker became more productive – Why is that important? • Because spending and debt should be viewed in relation to income • We automatically recognize this principle when we think about an individual family or business • What is true for an individual family is also true for nation – Budget-related figures such as government outlays, tax revenues, or government debt should be considered relative to a nation’s total income—as percentage of GDP • In 1959, federal government’s total outlays were 19% of GDP – In 2003, they were about 20%—reflecting a slight upward drift, but far from out of control – Our concerns should be based on, and expressed with, proper perspective 4 Spending, Taxes, and the Budget: Some Background • Our ultimate goal in this chapter is to understand how fiscal changes have affected, and continue to affect, macroeconomy – Why has national debt decreased in some years, risen slowly in other years, and risen very rapidly in still others? – Although state and local spending also play an important role in the macroeconomy • Most significant macroeconomic changes in recent decades have involved federal government 5 Government Outlays • Federal government’s outlays—total amount spent or disbursed by federal government in all of its activities—can be divided into three categories – Government purchases – Transfer payments – Interest on national debt 6 Government Purchases • Until 1980s, government purchases of goods and services were largest component of government spending – To understand how these purchases have changed over time, it’s essential to divide them into two categories • Military and non-military • • Federal government uses up only a tiny fraction or our national resources for non-military purposes Strongly contradicts a commonly held notion – Government spending is growing by leaps and bounds because of bloated federal bureaucracies • As a percentage of GDP, non-military government purchases have remained very low and stable – Have not contributed to growth in total government outlays • What about military purchases? – Here, we come to an even stronger conclusion • As a percentage of GDP, military purchases have declined dramatically over past several decades • Like non-military purchases, they have not contributed to upward drift in government outlays 7 Figure 1: Federal Government Purchases as a Percentage of GDP 8 Government Purchases • Military purchases were around 10% of GDP in 1959, fell almost continuously to about 3% in late 1990s, and started to rise again in early 2000s • Implications are tremendously important for thinking about recent past and future of federal government’s role – Decline in military spending in relation to GDP since early 1960s has made huge amounts of resources available for other purposes – Because military spending has little room to fall further and is likely to rise over next decade, there cannot be any similar freeing up of resources in coming years • Resources released from military spending eased many otherwise tough decisions about resources allocation – Likelihood of continued increases in military spending will have the opposite implication • Government will presented with difficult budget choices 9 Social Security and Other Transfers • Transfer programs provide cash and in-kind benefits to people whom federal government designates as needing help • Largest category is retirement benefits – Payments made by Social Security system to retired people • Second-largest category of transfers—and fastest-growing—occurs in health programs – Social Security system provides health-related benefits to everyone aged 62 and over through Medicare • Third and smallest of the three categories of transfers is income security – Programs to help poor families 10 Figure 2: Major Federal Transfer Programs, 2001 11 Social Security and Other Transfers • Have transfer payments been growing as a fraction of GDP? – Yes – All three categories of transfer programs have grown rapidly in recent decades • In recent decades, transfers have been the fastestgrowing part of the federal government outlays and are currently equal to about 12.5% of GDP • Growth in transfers relative to GDP was most rapid in 1970s during Nixon administration • Transfers are sensitive to ups and downs of the economy – Transfers as a fraction of GDP rise during recessions • Number of needy recipients rises in a recession • GDP falls in a recession 12 Figure 3: Federal Transfer Payments as a Percentage of GDP 13 Figure 4: Federal Government Interest Payments as a Percentage of GDP 14 Total Government Outlays • Figure 5 shows total outlays in relation to GDP over past several decades • Important things to notice in the figure – Fluctuations in government outlays over the period – Upward trend of federal outlays as a percentage of GDP • Over past several decades, and until early 1990s, federal government outlays as a percentage of GDP drifted upward – Main causes were increases in transfer payments and increases in interest on national debt that exceeded decreases in military spending – Downward trend in mid and late 1990s • From 1992 to 2000, federal government spending as a percentage of GDP fell steadily, although it remained a higher percentage of GDP than in 1959 – Main causes of decline were » Sharp decreases in military spending » More modest decreases in transfer payments relative to GDP during a long expansion 15 Figure 5: Total Federal Outlays As A Percentage of GDP 16 Total Government Outlays • However, Figure 5 also shows the appearance of a likely new trend – In early 2000s, due to a rise in military and domestic security purchases and continued increases in transfer • Federal government outlays as a percentage of GDP began rising, and seem likely to continue rising through decade • These trends in government outlays have important implications, but they are only half of the story • In order to understand their impact on the budget and the macroeconomy, we must look at the other side of the budget – Tax revenue 17 The Personal Income Tax • Most important source of revenue for federal government – Also most conspicuous and painful • Designed to be progressive – Tax those at the higher end of the income scale at higher rates than those at the lower end of the scale – Excuse poorest families from paying any tax at all • We can see from Table 2 that income tax is designed to be quite progressive • But tax system shown in the table does not reflect ways that people can avoid tax – Many people have deductions far above standard deduction • Also, remember that we are looking at federal personal income tax only 18 Table 2: The 2002 Personal Income Tax for a Married Couple with Two Children 19 The Social Security Tax • Applies to wage and salary income only – Put in place in 1936 to finance Social Security system created in that year • Because payroll tax applies only to earnings below a certain level, it is regressive • Social Security tax is actually largest tax paid by many Americans – Especially those with lower incomes 20 Other Federal Taxes • Federal government also collects around $300 billion annually from other taxes • Corporate profits tax is often criticized by economists because of two important problems – Only applies to corporations – Results in double taxation on the portion of corporate profits that corporations pay to their owners • Federal government also taxes consumption of certain products – Such as gasoline, alcohol, tobacco, and air travel • Called excise taxes 21 Trends in Federal Tax Revenue • Federal revenue trended upward from around 18% of GDP in early 1960s to around 20% in late 1990s • In early 2000s, federal tax revenues began a projected downward trend due to long-term reductions in tax rates • While trends in total federal revenue as a fraction of GDP have been rather mild, its composition has changed dramatically • Why have Social Security taxes grown in importance? – Social Security system operates on a pay-as-you-go principle • Taxes people who are working now in order to pay benefits to those who worked earlier and are now retired – For past several decades, system benefited from two favorable demographic factors • Relatively small number of retirees • Large number of taxpayers 22 Figure 6: Federal Government Revenue As A Percentage of GDP 23 Trends in Federal Tax Revenue • But now some demographic trends are working against the system – Improved health is allowing people to spend a larger fraction of their lives in retirement • At the same time, baby boomers will begin retiring en masse in late 2000s – Means greater numbers of people drawing benefits – These increased benefits will be funded by a smaller number of working taxpayers • As a result of these trends, government has been raising Social Security tax rates – Not just to keep the system solvent, but to go further » Building up reserves for retiring baby boomers 24 Trends in Federal Tax Revenue • Ultimately, however, keeping social security reserves in a separate account is important for psychological and political reasons – Making retirees and future retirees feel confident that money is being held for them – But focus on keeping trust fund solvent has had a side-effect • Caused government to continually raise regressive payroll tax rate over past few decades – Rather than rely on the progressive personal income tax to fund the system 25 The Federal Budget and the National Debt • Budget Surplus = Tax Revenue – Outlays • Budget Deficit = Outlays – Tax Revenue • Even though world has changed much since 1980s, reasons for the deficits of early 2000s seem like a repeat of history – A recession – Increased military spending – Sizeable, multi-year tax cut 26 Figure 7(a): The Federal Budget Deficit or Surplus as a Percentage of GDP 27 Figure 7(b): The Federal Budget Deficit or Surplus as a Percentage of GDP 28 The National Debt • Need to address some common confusion among three related, but very different, terms – Federal deficit – Federal surplus – National debt • Federal deficit and surplus are flow variables – Measure difference between government spending and tax revenue over a given period, usually a year – National debt, by contrast, is a stock variable • Measures total amount that federal government owes at a given point in time • Relationship between these terms – Each year government runs a deficit, it must borrow funds to finance it, adding to national debt 29 The National Debt • Can measure national debt as total value of government bonds held by public – Deficits—which add to the public’s holdings of government bonds—add to national debt – Surplus—which decrease the public’s bond holdings— subtract from national debt • Since cumulative total of government’s deficits has been greater than its surpluses – National debt has grown over past several decades • Rise and fall in national debt also explains another trend – Rise and fall in interest payments the government must make to those who hold government bonds 30 Figure 8: Federal Debt as a Percentage of GDP 31 How Economic Fluctuations Affect the Federal Budget • Economic fluctuations affect both transfer payments and tax revenues – In a recession, because transfers rise and tax revenue falls, federal budget deficit increases (or surplus decreases) • An expansion has the opposite effects on federal budget – Because transfers decrease and tax revenue rises, budget deficit decreases (or surplus increases) • Because business cycle has systematic effects on spending and revenue, economists find it useful to divide deficit into two components – Cyclical deficit • Part of federal budget deficit that varies with business cycle – Structural deficit • Part of federal budget deficit that is independent of business cycle • Cyclical changes in the budget are not a cause for concern, because they average out to about zero, as output fluctuates above and below potential output – Thus, cyclical deficit should not contribute to a long-run rise in national debt 32 How the Budget Affects Economic Fluctuations • Budget changes that occur automatically during expansions and recessions have an important impact – Help to make economic fluctuations milder than they would otherwise be • Changes in cyclical deficit make multiplier smaller, and thus act as an automatic stabilizer – Many features of federal tax and transfer systems act as automatic stabilizers • As economy goes into a recession, these features help to reduce decline in consumption spending – Also cause cyclical deficit to rise • As economy goes into an expansion, these features help to reduce rise in consumption spending – Also cause cyclical deficit to fall • Immediately raises a question – If automatic changes in budget help to stabilize economy, can government purposely change its spending or tax policy to make economy even more stable? 33 Countercyclical Fiscal Policy • When government uses fiscal policy to keep economy closer to potential GDP in shortrun, it is engaging in countercyclical fiscal policy • In 1960s and 1970s, many economists and government officials believed that countercyclical fiscal policy could be an effective tool to counteract business cycle – Today, however, economists tend to be more skeptical • Why? – Because counter-cyclical fiscal policy is plagued with several problems 34 Timing Problems • Takes many months or even longer for most fiscal changes to be enacted – Even if all goes smoothly • But in most cases, it will not go smoothly • Fed, by contrast, can increase or decrease money supply on very day it decides that change is necessary 35 Irreversibility • To be effective, countercyclical fiscal policy must be reversible – Many temporary tax changes become permanent as well • Public is never happy to see a tax cut reversed • Government is often reluctant to reverse a tax hike that has provided additional revenue for government programs • Reversing monetary policy, while not painless, is easier to do – Moreover, public and Congress have largely accepted Fed’s role in stabilizing the economy – Expect that interest rate will be adjusted as condition of economy changes 36 The Fed’s Reaction • Even if government attempted to stabilize economy with fiscal policy, it could usually not do so very effectively – Because Fed would not allow it – Fed views most changes in fiscal policy just as it views other changes in aggregate expenditure • As a change to be neutralized – As long as Fed remains free to set its own course, and sees its goal as stabilizing the economy at full employment with low inflation • There is generally no opportunity—and no need—for countercyclical fiscal policy 37 The Effects of Fiscal Changes in the Long-Run • Fiscal changes have important effects on economy over long-run • Important conclusions about fiscal policy in classical model – Government’s tax transfer policies can influence rate of labor force participation – Government’s tax policies can directly influence rate of investment spending on new capital and R&D – Government’s budget deficit can influence investment spending as well • And, from this chapter, you’ve learned the following – Budget deficits add to national debt • But what are consequences of adding to national debt? 38 The National Debt • On a billboard in midtown Manhattan, a giant clock-like digital display tracks U.S. national debt and how it changes each minute • National debt clock was one of several public relations campaigns that spread fear among American public • Economists do have concerns about national debt – But they are very different from concerns suggested by national debt clock or other similar gimmicks 39 Mythical Concerns About the National Debt • What bothers many people about a growing national debt is belief that one day we will have to pay it all back – But although we might choose to repay national debt, we do not have to • Ever – How could a government keep borrowing funds without ever paying them back? • Surely, no business could behave that way • But actually, many successful business do behave that way, and continue to prosper • Of course, this does not mean that any size debt would be prudent – Debt and interest payments have meaning only in relation to income • All of these observations apply to federal government as well – As long as nation’s total income is rising, government can safely take on more debt 40 Mythical Concerns About the National Debt • Federal government could pay back national debt – By running budget surpluses for many years • How large could annual deficits be without making national debt a looming danger? • As long as total national income grows at least as fast as interest payments on debt – Ratio of interest payments to income will not grow – In that case, we could continue to pay interest without increasing average tax rate on U.S. citizens 41 A National Debt That Is Growing Too Rapidly • Important minimal guideline for responsible government is that debt should grow no faster than nominal GDP • Important implications – To prevent a long-term disaster after too-rapid growth in the debt, we do not have to run budget surpluses – Even a temporary violation of the guideline is costly • How can tax burden be brought back down after a temporary violation of the guideline? – Raise growth rate of nominal GDP above growth rate of the debt for some time – Lower growth rate of debt below growth rate of nominal GDP for some time 42 A National Debt That Is Growing Too Rapidly • But these solutions are costly to society – Consider • Raising growth rate of nominal GDP • Slowing down growth rate of debt below growth rate of nominal GDP • A debt that rises too fast—faster than nominal GDP—for some period of time will impose an opportunity cost in the future – Cost will be either a permanently higher tax burden, a period of inflation, or a temporary period of reduced government outlays or higher taxes relative to GDP • This is not just theoretical, as U.S. experience during 1970s and 1980s demonstrates – Fortunately, 1990s was a period of prolonged expansion and reduced military purchases • Opportunity cost of lower deficits was not as painful as it might otherwise have been 43 A Debt Approaching the National Credit Limit • If debt were to rise too rapidly relative to GDP, for too long – There is a theoretical danger of reaching nation’s credit limit • Amount of debt that would make lenders worry about government’s ability to continue paying interest • While this is a theoretically sound danger of a rapidly-rising debt – Doubtful United States has been anywhere near that limit during recent decades 44 Failing to Account for Future Obligations • Many students reading this book are getting financial help from parents to pay costs of college – Planning for this obligation may have begun very early—perhaps even before you knew what college was • Federal government is in an analogous situation – It has effectively promised to provide Medicare and social security payments to millions of people at some time in the future • Of course, trying to project total federal revenues and outlays over the next 75 years, 50 years, or even 15 years would be guesswork at best • This uncertainty over future projections has led to divergent views about policy • These divergent views formed part of background for controversy over Bush tax cuts 45 Using the Theory: The Bush Tax Cuts of 2001 and 2003 • In 2001, Bush administration cut taxes over ten years by $1.35 trillion, and in 2003, by another $350 billion • Much of debate over tax reductions had to do with distribution – Whether cuts were apportioned fairly among different income groups – But they also raised two important macroeconomic issues that we’ve discussed in this chapter 46 The Short Run: Countercyclical Fiscal Policy? • Tax cuts of 2001 and 2003 seem like perfect examples of well-timed countercyclical fiscal policy – Does this show that countercyclical fiscal policy works? • Not really, because a closer look suggests that neither tax cut was really designed for that purpose – Tax cut of June 2001 had actually been proposed more than 18 months earlier by presidential candidate Bush as a long-run policy measure, to promote growth in potential output – Fact that tax reduction was enacted during a recession was a stroke of luck—not a example of well-timed short-run fiscal policy • Remember that countercyclical fiscal policy requires that changes in taxes be reversible when economic conditions change 47 The Short Run: Countercyclical Fiscal Policy? • As so often happens in macroeconomic debates, however, politics took over • In between these two cuts, however, Bush administration proposed a smaller, $60 billion tax cut – If there was ever an opportunity to showcase effectiveness of countercyclical fiscal policy, this was it – But tax bill was debated for a full six months in House and Senate, and was not signed by President until March, 2002 48 The Long Run: The Tax Cuts and the National Debt • Table 3 shows two different projections of budget deficits and national debt • Judging by OMB’s numbers, it appears that the administration’s fiscal policy is an example of a temporary violation of the guideline for responsible government – Debt is rising faster than GDP through 2006, and then stabilizing and descending • What do these numbers tell us? – Certainly not a debt disaster – But a fiscal policy with future costs • Where does this rise in debt come from? – Some of the early rise comes from cyclical deficits – But continued deficits in 2006 and beyond—when the economy is assumed to have recovered—are mostly structural deficits 49 Table 3: Projected Budget Deficits and the Rising National Debt 50 The Long Run: The Tax Cuts and the National Debt • Look at lower half of Table 3 – Shows numbers put out by Democratic Caucus of House Budget Committee in a press release, within days of OMB documents release – Shows a more sharply rising deficit, and what looks like a long-run violation of guideline for responsible government – Note that Democratic Caucus projects 10 years forward instead of five – But that only accounts for part of dramatic difference in the fiscal story each side tells • What accounts for the rest? 51 Figure 9: Countercyclical Fiscal Policy 52 The Long Run: The Tax Cuts and The National Debt • The answer is – Assumptions behind the numbers • Using Democratic numbers, virtually all of the rise in the debt can be attributed to tax cuts of some form – Either original cuts in 2001 and 2003, – Or expected extensions and further reductions Administration has discussed • Based on either set of numbers, we are entering a period of rising debt that will entail the kinds of future costs we’ve discussed in the chapter • Ultimately, our conclusions about any economic policy must compare costs with benefits 53