8. ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE

advertisement

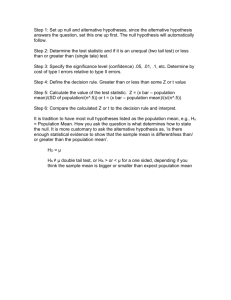

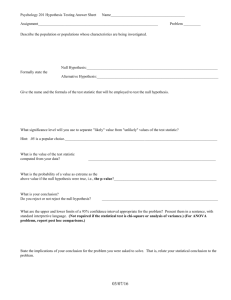

8. ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE 8.1 Elements of a Designed Experiment 8.2 Experimental Design 8.3 Multiple Comparisons of Means 8.4 Factorial Experiments 8.1 Elements of a Designed Experiment Definition 1: The response variable is the variable of interest to be measured in the experiment. We also refer to the response as the dependent variable. Definition 2: Factors are those variables whose effect on the response is of interest to the experimenter. Quantitative factors are measured on a numerical scale, whereas qualitative factors are those that are not (naturally) measured on a numerical scale. Definition 3: Factor levels are the values of the factor utilized in the experiment. Definition 4: The Treatments of an experiment are the factor-level combination utilized Definition 5: An experimental unit is the object on which the response of factors are observed or measured. Figure 8a. Sampling experiment: Process and Terminology 8.2 Experimental Design 8.2.1 8.2.2 8.2.3 Complete Randomization The Randomized Block Steps for Conducting a ANOVA for a Randomized Block Design 8.2.1 The Completely Randomized Design Definition: A completely randomized design is a design for which independent random samples of experimental units are selected for each treatment*. *We use completely randomized design to refer to both designed and observational experiments. Table 8a. Complete Randomization D A C C B D B A D C B D A B C A •We could divide the land into 4 X 4 = 16 plot and assign each treatment to four blocks chosen completely at random. •Purposes: to eliminate various source of error. 8.2.2 The Randomized Block Design Consist of two-step procedures: 1. Matched sets of experimental units called block, are formed, each block consisting of p experimental units (where p is the number of treatments). The b blocks should consist of experimental units that are the similar as possible. 2. One experimental unit from each block is randomly assigned to each treatment, resulting in a total of n = bp responses. Table 8b. Randomized Block I II III C B A D A B D C B C D A IV A D C B • The treatment A, B, C and D are introduced in random order within each block: I, II, III, and IV, but it is necessary to have complete set of treatment for each block. • Purposes: Used when it is desired to control one source of error or variability, namely, the difference in block. Figure 8b. Partitioning of the Total Sum of Squares for the Randomized Block Design 8.2.3 Steps for Conducting an ANOVA for a Randomized Block Design 1. Be sure the design consists of blocks (preferably, blocks of homogeneous experimental units) and that each treatments randomly assigned to one experimental unit in each block. 2. If possible, check the assumptions of normality and equal variances for all block-treatment combinations.[Note:This maybe difficult to do since the design will likely have only one observation for each block-treatment combination.] 3. 4. Create an ANOVA summary table that specifies the variability attributable to Treatments, Blocks and Error, and that leads to the calculation of the F statistic to test the null hypothesis that the treatment means are equal in the population. Use a statistical software package or the calculation formulas to obtain the necessary numerical ingredients. If the F-test leads to the conclusion that the means differ, use the Bonferroni, Tukey, or similar procedure to conduct multiple comparisons of as many of the pairs of means as you wish. Use the results to summarize the statistically significantly differences among the treatment means. Remember that, in general, the randomized block design cannot be used to form confidence intervals for individual treatment means. 5. If the F-test leads to the non-rejection of the null hypothesis that the treatment means are equal, several possibilities exist: a. The treatment means are equal-that is, the null hypothesis is true. b. The treatment means really differ, but other important factors affecting the ii response are not accounted for by the randomized block design, These factors inflate the sampling variability, as measured by MSE, resulting in smaller values of the F statistic. Either increase the sample size for each treatment, or conduct an experiment that accounts for the other factors affecting the response. Do not automatically reach the former conclusions, since the possibility of a type II error must be considered if you accept H0. 6. If desired, conduct the F-test of the null hypothesis that the block means are equal. Rejection of this hypothesis lends statistical support to the utilization of the randomized block design. 8.3 Multiple Comparisons of Means The choice of a multiple comparisons method in ANOVA will depend on the type of experimental design used and the comparisons of interest to the analyst. For example, Turkey ( 1949) developed his procedure specifically for pairwise comparisons when the sample sizes of the treatments are equal. The Bonferroni method (see Miller, 1981), like the Tukey procedure, can be applied when pair wise comparisons are of interest; however, Bonferroni's method does not require equal sample sizes. Scheffe (1953) developed a more general procedure for comparing all possible linear combinations of treatment means ( called contrasts). Consequently, when making pairwise comparisons, the confidence intervals produced by Scheffe's method will generally be wider than the Tukey or Bonferroni confidence intervals. 8.4 Factorial Experiments Definition: A complete factorial experiment is one in which every factor-level combination is utilized. That is, the number of treatments in the experiments equals the total number of factor-level combinations. Table 8c. Schematic Layout of TwoFactor Factorial Experiment Factor B at b levels Levels 1 2 Factor A 3 at a levels a 1 Trt. 1 Trt. b 1 Trt. 2b 1 Trt. (a - 1)b 1 2 Trt. 2 Trt. b 2 Trt. 2b 2 Trt. (a - 1)b 2 3 Trt. 3 Trt. b 3 Trt. 2b 3 Trt. ( a - 1)b 3 b Trt. b Trt. 2b Trt. 3b1 Trt. ab Figure 8c. Illustration of possible treatment effect: Factorial experiment Figure 8d.Partitioning the Total Sum of Squares for a two-factor factorial 8.5.1 Procedures for Analysis of Two-Factor Factorial Experiment 1. 2. Partition the Total Sum of Squares into the Treatment and Error components (stage 1 of Figure 8d). Use either a statistic at software package or the calculation formulas to accomplish the partitioning. Use the F-ratio of Mean Square for Treatments to Mean Square for Error to test the null hypothesis that the treatment means are equal. a. If the test results in nonrejection of the null hypothesis, consider refining the experiment by increasing the number of replications or introducing other factors. Also consider the possibility that the response is unrelated to the two factors. b. If the result in rejection of the null hypothesis, then proceed to step 3. 3. Partition the Treatment Sum of Squares into the Main Effect and Interaction Sum of Squares (stage 2 of Figure 8b). Use either a statistical software package or the calculation formulas to accomplish the partitioning. 4. Test the null hypothesis that factors A and B do not interact to affect the response by computing the F-ratio of the Mean Square for Interaction to the Mean Square for Error. a. If the test results in nonrejection of the null hypothesis, proceed to step 5. b. If the test results in rejection of the null hypothesis, conclude that the two factors interact to affect the mean response. Then proceed to step 6a. 5. Conduct tests of two null hypotheses that the mean response is the same at each level of factor A and factor B. Compute two F-ratios by comparing the Mean Square for each Factor Main Effect to the Mean Square for Error. a. If one or both tests result in rejection of the null hypothesis, conclude that the factor affect the mean response. Proceed to step 6b. b. If both tests result in nonrejection, an apparent contradiction has occurred. Although the treatment means apparently differ (step 2 test), the interaction (step 4) and main effect (step 5) tests have not supported that result, Further experimentation is advised. 6. Compare the means: a. If the test for interaction (step 4) is significant, use a multiple comparisons procedure to compare any or all pairs of the treatment means. b. If the test for one or both main effects (step 5) is significant, use the multiple comparisons procedure to compare the pairs of means corresponding to the levels of the significant factor (s). 8.5.2 Test Conducted in Analysis of Factorial Experiments: Completely Randomized Design, r Replicates per Treatment 1. Test for Treatment Means H0 : No difference among the ab treatment means Ha : At least two treatment means differ MST Test statistic : F MSE Rejection region: F F based on ( ab 1) numerator and (n ab) denominator degrees of freedom [Note: n = abr]. 2. Test For Factor Interaction H0 : Factor A and B do not interact to affect the response mean Ha : Factor A and B do interact to affect the response mean MS ( AB) Test statistic : F MSE Rejection region: F F based on (a 1)(b 1) numerator ( n ab) and denominator degrees of freedom. 3. Test For Main Effect Of Factor A H0 : No difference among the a mean levels of factor A Ha : At least two factor A mean levels differ MS ( A) Test statistic : F MSE Rejection region: F F based on ( a 1) numerator and ( n ab) denominator degrees of freedom. 4. Test For Main Effect Of Factor B H0 : No difference among the b mean levels of factor B Ha : At least two factor B mean levels differ MS ( B) Test statistic : F MSE Rejection region: F F based on (b 1) numerator and ( n ab) denominator degrees of freedom. 5. Assumptions For All Test 1. 2. 3. The response distribution for each factor-level combination (treatment) is normal The response variance is constant for all treatments Random and independent samples of experimental units are associated with each treatment.