Annual Report: 1132840 Losos, Elizabeth - Principal Investigator Annual Report for Period:

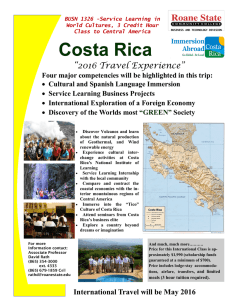

advertisement