MONUC and the Relevance of Coherent Chapter 3

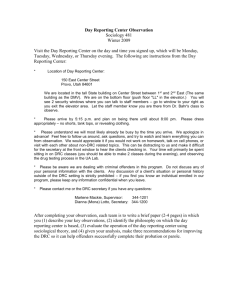

advertisement