Corporate Governance and the Firm’s Workforce Inessa Liskovich January 15, 2015

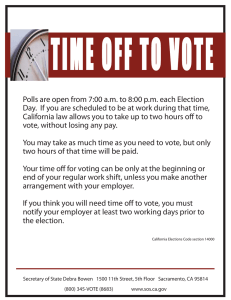

advertisement