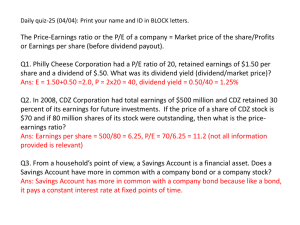

Does bundling matter?

advertisement