ARCHAEOLOGY OF NORTHWESTERN OKLAHOMA: AN OVERVIEW A Thesis by Mackenzie Diane Stout

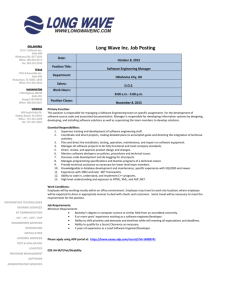

advertisement