THE PROCESS EVALUATION OF PROJECT CONNECTION LESSONS ON LINKING DRUG COURTS AND COMMUNITIES

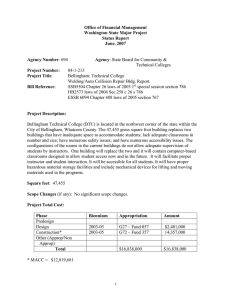

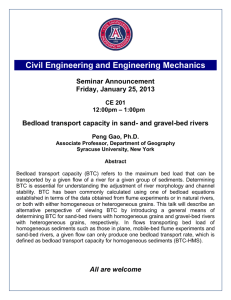

advertisement