CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE TRANSCULTURATING CULTURAL MEMORY IN NATIVE AMERICAN PERFORMANCE

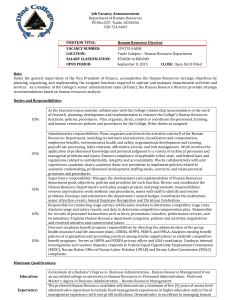

advertisement