Part III: Swedish Lessons

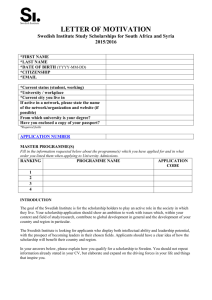

advertisement