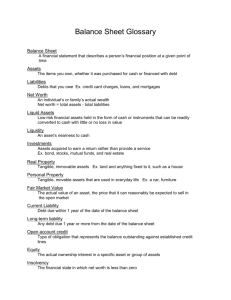

T B S L

advertisement