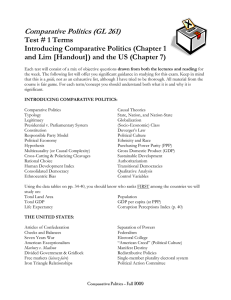

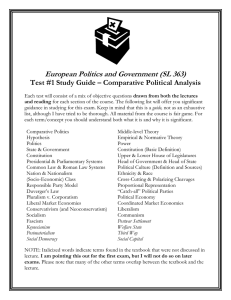

Comparative Politics

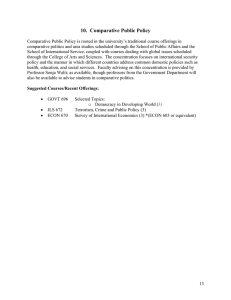

advertisement