Tax Considerations in a Universal Pension System (UPS)

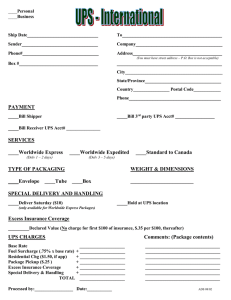

advertisement