Top Teams in a Crisis

advertisement

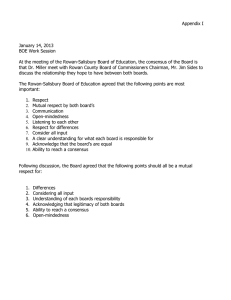

Top Teams in a Crisis Interviewer: Steve Macaulay Interviewee: Professor Andrew Kakabadse October, 2008 SM: The credit crunch has caused enormous problems throughout the world. It has affected organisations to the point that many of them are in crisis, so it’s very relevant to look at the leadership of those companies and how they are behaving in these times. So Andrew, you have got a lot of experience of working with companies at the senior level – tell me a bit more about that. AK The experience of working with companies is really looking at top teams, the role of chief executives, boards, the role of chairmen, the contribution of board directors, the way the top management team links with the board and vice versa. And the overall message is that it is a symbiotic relationship, but you have to make it work. It is not a scribed or a prescribed approach. I have known many boards, and the chairman of the board takes on what would be in any other organisation, the responsibilities of the CEO, and the CEO taking on the responsibilities of the chairman. And interestingly enough, it works. It works because the CEO and chairman have sat down and talked to each other; they have allocated their responsibilities by where they stand in the market place and what is right for the company; they have sorted out what should be management’s contribution to the board and the board’s contribution to management. So it is an interesting relationship that requires continuous redefinition if that relationship is going to work and we need it to work. SM: It needs to work particularly in times of crisis. I would like to focus in on that and say what happens when a board suddenly reaches a crisis time? AK We have a major problem because the board should never have suddenly reached a crisis time and the operative word there is suddenly. If suddenly something happens, it tells you that there has been a problem there for a long time and either management has not been informing the board, or the chairman of the board has not been informing the board and keeping things quiet, or there has been some sort of process between chairman and CEO of not talking to each other – but in a well run company, there is no ‘suddenly’. Crisis has been planned for, considered and is coming and there has been good risk vulnerability analysis taking place. SM: So what would you look for then in the current situation to say are they handling this well at the senior level? AK And the current situation being the credit crisis? I think there has to be a distinction here between poor management and surprise, and it is well worth stating that the credit situation which most people see as that of liquidity – there isn’t enough credit – is not just the problem. There is the problem of available capital to continue trading in the way you are and in that sense many people are surprised – not just boards and top teams, but many citizens and this is not the fault of just a few greedy bankers or banks that were taking unnecessary risks: this is a major concern with shareholder value, thinking and application, of which governments played a distinct part. Most notably of all was the British government that had created from Thatcher times, the idea of the freest market in the world, it was not free in manufacturing cars, it was free in terms of money. We were the financial centre of the world – London was. So fundamentally what was happening was not only were we investing in housing, or poor quality housing with poor quality customers, we were trading on impossible positions for the last twenty years. So the whole question of what is a derivative; where do you take a position on oil prices in twenty five years; how many times can you sell a promissory note to X, Y and Z and the billions that went with that affects us all. And because we had got so used to that, I would think that most people who have no intimate knowledge of the financial industry were caught by surprise. So I cannot blame boards and top teams in terms of being caught by surprise by what is happening now – they just did not know and all their normal parameters of risk assessment were probably quite well applied. So if we leave aside the issue of surprise and then we go into the issue of poor leadership, with those organisations that had tensions, what this credit crunch has done, it has brought those tensions to the surface. Usually those tensions for some reason or other were kept under control in some sort of way. So there could have been a division between the CEO and the top team members, there could have been a division between the top team and the country managers who felt that they were not being sufficiently invested in or some of corporate centre policies made no sense for them as a country, but they made sense globally. There could have been a lack of information and insight going to the board – the board was too involved with detail and never really appreciated the business. And I have to say that was one finding from the British survey of boards, when we compared them to other countries, it was interesting to see that the managers who sit on boards – the professional managers who sit on boards – from the FOOTSIE 100 companies to the FOOTSIE 350 companies, did not respect their chairman or non executive directors. So if the chairman and non exec directors say ‘Guys we are doing great on CSR, share price, corporate reputation’ – think of all the hard and soft factors – on every one of those factors, the board directors took a different position and basically said we are not doing as well as they think we are. In Australia it was the exact reverse, there was harmony. And one of the reasons for that was that the Australian part time, non executive board director tended to have a much smaller portfolio, they tended to spend much more time on each company, they tended to get involved in much greater detail about the company and so they knew the company’s strengths and weaknesses quite intimately. So the average NED portfolio for the Australians was about three to four boards – I know people in England who have got 17 to 21 board directorships and another three chairmanships, and I have to ask you what are they doing? When they go to a meeting what do they think they are doing when they look at the papers in front of them? So the credit crunch has highlighted that practice – that you can no longer be a board director by simply turning up to a meeting and having read a few papers. It’s a professional role and you have to know how to handle that professional role and not overlap into management as well. The credit crunch will also have shown divisions of vision, where the top team itself was not fully aware of what was happening. So the credit crunch will have caught people – even the best run companies – by surprise and we must distinguish them and some of the blaming that may naturally take place from feeling irritated that you are such a good company and yet you are being hurt by the activities of a few, to the companies that were poor to begin with and their tensions have been surfaced. I think once it is realised how far this current financial crisis was embedded into our whole societies and the irritation of the guys who were good is simply an expression of irritation and not an expression of poor management, then we will see the reality of how poorly managed those other organisations are, or were. SM I would imagine if we were to sit in on a boardroom at the moment, there would be almost a feeling of panic in the room, of people saying to themselves where on earth do we go next, with the real fear that they could lose their jobs. AK: Absolutely, and it’s the same fear that people would have with their deposit accounts, especially if they have been conscientious citizens and they have been trying to save up for their future. It’s exactly the same fear that you are going to have between a leader of a council and the chief executive of a county council or some sort of urban borough organisation, government organisation, who have invested their pension funds in financial instruments for the future and those financial instruments have now just fallen apart. So it is not just boardrooms, it is right across the board. And because there was no real understanding of the intricacy of the financial markets, but also the stupidity of them. The intricacy was the mathematical analysis of how to get further percentage points by looking and placing financial instruments and looking at the trends of markets based on trends from previous years. The stupidity was, that you are basically trading paper and as soon as somebody pricks the bubble, that this paper is fundamentally worthless because there is nothing backing it, the whole thing falls apart. But so many people have been caught in trading paper for the last twenty to twenty five years, and we have all benefitted. So again, you still come back to what is the nature of the panic? If the nature of the panic is all of sudden the very platform upon which we stood has been taken away from us, I think we have a right to panic. And I think we have a right to get worried, and I think we have a right to express that. If what has happened as a result of that is poor management has been brought to the surface, then we should start getting rid of those poor managers who are not doing their job. SM So if a board came to you at the moment and said, Andrew, can you please give me some advice here, we are in a new position that we have never been in before – how do we best handle this, not the specifics, but how do we best go about handling this? What would you say? AK You have to go to basics and you fundamentally ask the board, the management to get together and see whether they can agree on what is the core of that business. Do we understand what is core and critical to this business? Do we understand what is our critical differentiating factor? Do we understand what is our competitive advantage? And don’t be surprised to find amongst people who have been working together for quite some time, that they hold different views. Two or three different views is normal – we can sort of pull them together. When you start having seven or eight completely different views and you never voiced them in the first place, there we have a problem. Now if we can at least agree on the core and critical factors that differentiate us and the advantage to continue being competitive is there, the next question is should these assets now be linked with other assets – should we go for a merger or invite an acquisition, or should we sell off parts of the business? So how do we continue to position these assets and should we position these assets in the way we have positioned them before? So there we now start looking at portfolio and we are looking at structural design. Do we still want a divisional structure, for example? Do we want this major part of the business sold off in order to provide funding for other parts of the business? And once you have gone through that debate you can then go into the actual management and leadership of the organisation, so that we get efficiency and effectiveness of application. So you do start vision, mission, shape and portfolio of the business and then the way we run it. Now, if what you surface is we never understood the vision and mission, and we were deliberately fighting each other on that and the portfolio, some of us knew it was wrong and yet we played the game ‘it was right’ but then undermined the policies of the centre, now we have a serious concern which under these present conditions must raise questions about the tenure of those executives that allowed this situation to continue for all these past years. SM Andrew that is a very sobering and insightful series of thoughts. Thank you. AK Thank you.